JET MORGAN:

‘JOURNEYS INTO SPACE’

During the long-lost 1950’s Jet Morgan was a high-profile

serious rival for Dan Dare’s title as most famous space-faring Brit.

The reason was a trilogy of BBC radio serials which ensured that Jet

– with companions Doc, Mitch and Lemmy, became national figures

at the very dawn of the Space Age. Those radio-serials are now

available for reappraisal in CD box-sets, and their print spin-off tales in

‘Eagle’s glossy rival ‘Express’ can be enjoyed again in reprint editions.

Andrew Darlington re-reads them all…

‘THE STORY THAT ENTHRALLED MILLIONS…’

Commissioned by BBC Head of Variety Michael Standing, Captain Andrew ‘Jet’ Morgan made his first ‘Journey Into Space’ in the serial of that title which began on 21 September 1953.

Immediately a smash-hit with space-minded youngsters, the sequels inevitably followed. Like a Rock group the cast consists of a four-piece dynamic, with Jet (voiced by Andrew Faulds) as the smooth Scottish controlling centre. His call-sign – ‘Captain Morgan’, prompts to mind both the infamous buccaneer… and a brand of Rum. He’s flanked by blunt-speaking Stephen ‘Mitch’ Mitchell (variously voiced by Bruce Beeby, Don Sharp, and David Williams). He’s the man who designed the original atomic-powered moon-ship, and because he’s Australian he’s given to saying things like ‘Strewth’ and ‘Good Show Cobber!’. There’s able Doc Matthews (Guy Kingsley-Poynter), the American director of space medicine from the New Mexico project. It’s his diaries that provide the voice-over narration, and the first-person presence in the novelisations. Lastly – as the Ringo-style knockabout drummer of the group, Chirpy Cockney Lemuel ‘Lemmy’ Barnet provides the comic light relief. He’d formerly been Jet’s radio operator on a sub-orbital passenger superstrato-liner, crossing the Atlantic in two hours. Lemmy was originally voiced by David Kossoff, then by Alfie Bass – and he may just be the source of the Motorhead vocalist’s nom-de-guerre! The four-way character interaction breathes life into the drama, anticipating the Kirk-Spock-McCoy-Scotty banter that enlivens the bridge of the ‘Enterprise’. Ultra velvet-voiced DJ David Jacobs was a vital additional element across all of the subsequent series, appearing in twenty-two different character roles, finally including Jet himself in a one-off ‘Frozen In Time’ episode. It’s his voice eerily intoning ‘Jour-ney Int-to Spaaace’ that introduces each episode, sending excited frissons of thrills through radio listeners.

Charles Frederick William Chilton was the radio producer and scriptwriter responsible for it all. His father was killed during World War I before he was born in Sandwich Street 15th June 1917. Brought up initially by his mother and stepfather, living five-in-a-room in Kings Cross, he was cared for by his grandmother after his mother’s death in the great 1920 flu epidemic. He joined the BBC as a messenger boy aged fifteen, after a year in a factory ‘which I hated’. He later told how he simply ‘walked in’ to the newly opened Broadcasting House and ‘asked for a job’. He believes the Calvinist director-general of the BBC, John Reith – terribly scarred in 1916, was sympathetically inclined to help the young ‘war orphan’, and the corporation not only employed him but sponsored his Evening School further education. Soon graduating to the position of Record Library assistant, reports in ‘Melody Maker’ track his broadcasting career – that in July 1943, after five years as producer-presenter of ‘Radio Rhythm Club’ he’d ‘failed his voice test’ and would no longer act as announcer for the programme, only for a subsequent report – in April 1952, that he was to edit a new-style ‘Jazz Club’, alternating records with live shows. Eventually he was doing production work for ‘The Goon Show’ and introducing ‘The Glums’ family into Jimmy Edwards’ ‘Take It From Here’. Until he was called upon to plot and author the exploits of Jet and his companions as they defend Earth against Martians and sundry other threats.

At first, the debut ‘Tale Of The Future’ appears to be a routine first moon-landing story. ‘The Moon?’ says Lemmy, ‘no distance at all. A fourpenny bus ride!’ But there’s an opening shock when, as they lift-off from the lunar surface for the return trip, they discover that inexplicably there’s only reserve tank fuel left, only one-tenth of the oxygen they should have, and their food supply is strangely altered. Events must have occurred of which they’re not aware! Using Doc’s diaries the action then backtracks to the mission preparations, and the initial launch from a remote Australian site, ‘outback of the Outback’. In the light of subsequent real-time history it’s instructive to note that in Chilton’s continuum the first rocket into space happened in 1957, followed by American pre-election funding-cuts halting its embryonic space programme. Russia’s participation is not even mentioned. Instead it’s left to a British Commonwealth of Nations consortium to launch the two-stage ‘Luna’ spacecraft in November 1965. A monumental venture, but not unfamiliar to those who’d seen George Pal’s movie ‘Destination Moon’ (1950) a few years earlier – clear down to Lemmy’s free-fall harmonica solo of ‘Old Kent Road’. At first things go fine, apart from a communications breakdown and the strange ‘surging eerie symphony’ Lemmy picks up in its place. Until – stranded on the lunar surface adjacent to the Bay of Rainbows by a power-failure, they encounter a flying saucer. From that point on, things become increasingly extravagant. More saucers appear from the dark side of the moon – which, of course, was still unseen in 1954! Accelerated and accidentally drawn into trackless space by the pursuit they reach a mystery planet of continual rainfall. By identifying the constellations – with Vega as the Pole Star, Jet reasons that they’ve returned through time to arrive on prehistoric Earth at the time of an Ice Age. There are saucers here too, which convey them to an underground city of domes. A ‘time travelling’ alien, resembling an armadillo with a red-&-blue mandrill-face, voiced by Deryck Guyler in a tone ‘neither friendly, antagonistic, calm nor excited’, explains his race are survivors of a nova ‘from the other side of the universe’. Taking temporary refuge on Earth they are now relocating to Venus fearing the ‘forest creatures’, who turn out to be primitive Neanderthaloids. Recognising the human trait of violence inherited from these predecessors, the alien only returns the crew to 1965 after wiping their memory of events… overlooking the written narrative in Doc’s diary!

While citing Jet Morgan as ‘a phenomenon which must have shaken the BBC considerably, delighted the minority of enthusiasts, and was probably more responsible for the increasing public interest in science fiction than any other factor’, Leslie Flood in ‘New Worlds’ (No.32, February 1955) writes ‘one is inclined to believe the rumours that Chilton had to write on frantically to lengthen the original six-episode version the BBC had planned, in order to take advantage of its sudden popularity, but the later incidents of the aliens on the Moon and the time-travel kidnap are neatly tied on’. Aired Monday evenings at 7:30pm those Journeys Into Space became ‘by far the most significant (radio) enterprise’ thus far undertaken by the BBC, and ‘radio’s nearest equivalent to’ and direct predecessor of ‘such serials as the Quatermass trilogy’ – according to David Pringle’s ‘The Ultimate Encyclopedia Of Science Fiction’. AB Perkins agrees, adding that ‘by 1955 the programme reached five-million listeners, the largest UK radio audience ever, and deservedly so, since no previous SF radio drama had equalled its narrative vigour’ (in Peter Nicholls’ ‘The Encyclopedia Of Science Fiction’). There were other, more nuanced commentators. Chilton himself remembers how critics described it as ‘a Western on the Moon’. Kingsley Amis suggests that ‘radio is often spoken of as the most promising of the three media for science fiction’ (alongside TV and films), adding the proviso that ‘I was spoilt, perhaps, by sitting through ‘Journey Into Space’, an interminable saga on the BBC’ (in his ‘New Maps Of Hell’). And it’s true that Chilton’s productions rarely exploit the full potential of that most promising of media.

‘AN ALIEN CIVILISATION PREPARES TO CONQUER

EARTH – AND ONLY FOUR MEN CAN SAVE HER…’

The sequel – ‘The Red Planet’, jumps ahead to 1971 with the Earth enjoying a decade of peace. Jet’s ‘Discovery’ leads a Mars-bound fleet of nine ships with twenty crewmen, on an expedition troubled by a number of mysterious happenings, including a meteor-swarm that deliberately shifts to block their journey, and crewman Whitaker (Anthony Marriott) on Freighter No.2 who turns out to have been born in 1893, before vanishing in 1924! Landing at the Martian north-pole where they set up a base, Jet dreams of a ruined city in a valley, which they later find, and there are ‘conditioned men’ – stolen Earth-humans who are able to breathe the thin Martian air, and achieve unnatural longevity during their Mars exile. They also encounter a homestead of sheep-farmers who believe they are living in Australia in 1939. Although their flock consists of Martian ant-eaters in the Argyre Desert (Mare Australis), there’s a dingo-hunter and even a Flying Doctor in a Martian sphere to complete the hypnotically-induced illusion. Mitch is the only member of the team who remains entirely immune from mind-control. The familiar SF-trope of a replica-Earth society located on an alien world – used by Ray Bradbury in his ‘Martian Chronicles’, is more usually an avoidance strategy around the budgetry restrictions of low-cost TV or movie studios. So that it may look like Earth, but we know it’s really Mars. A device totally unnecessary for radio where expensive sets are hardly a consideration, and the only limits are those of the power of words to evoke wondrous landscapes or fantastic towering cities, augmented by a few eerie theramin-quivers from the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. Maybe Chilton felt he had to work to the expectations of his mainstream audience? Maybe its success indicates he was correct? His is a Mars of pyramid cities thousands of years old located in the oasis junctions of canals. Although they fail to locate a single living Martian, in the city of Lacus Solis the team discover an underground factory operated by hundreds of conditioned Earthmen who are constructing spherical spaceships – believing they’re on Earth building aircraft for World War II. Jet learns the Martians intend using this fleet to invade Earth in 1986, escaping with only three remaining ships, and eight men, to warn the world of its imminent danger.

In a direct continuation ‘The World In Peril’ opens with the crew debriefing when Martian spheres are detected 1,000-miles above in Earth orbit, within what appear to be asteroids. ‘Change at Clapham Junction’ quips Lemmy as they blast off to investigate. An extended preamble involves a crashed sphere in the Lake District and an attempt to kidnap Jet’s team. It’s been suggested the success of the radio series justified extending its run with a certain amount of added padding. Hence the presence of ‘conditioned types’ creating hazards on Earth by acting as an active reconnaissance party or fifth column. Then Martian spheres are seen above the Bay of Rainbows lunar base where the return to Mars is under preparation. Eventually the ‘Discovery’ sets out for the Red Planet, landing near the wreck of Freighter No.2 guided by the deceptive voice of engineer Frank Rogers, a lost ‘conditioned’ member of the original expedition. By episode-eight, following a sudden attack, the team find themselves aboard Asteroid-734, one of a fleet of hollowed-out planetoids crewed by conditioned men, including Rogers, who are travelling towards target-Earth. The invasion is already underway. Chilton sets this instalment, as they fumble around in total darkness, as a snipe at something radio can do that TV cannot – as he claimed, ‘radio is much better than television because you get better pictures’. In another tease the Martians intend using a simultaneous hypnotic TV-broadcast to activate a massive infiltration of ‘conditioned types’ to control human population. Lunar Controller Jack Evans turns out to be a Martian agent. He explains how ‘television is the most important weapon at our disposal’. ‘Slaves of a television screen’ murmurs Lemmy, who trashes the Martian electronic computer-brain – called Nicholas, or ‘Old Nick’ to Lemmy!, which is a big square construction ‘as tall as a house and as long as a street’. The escaping team return to Mars in a stolen sphere, and use their expedition’s orbiting Freighter to re-contact and warn Earth, all the while pursued by Martian asteroids. Forced to transfer to the flagship Jet finally meets the sole Martian, last of a race of gentle giants (a single alien, like the solitary Time-Traveller from the first adventure). In fact, Earth legends of giants descending from beanstalks stem from an earlier Martian colonisation attempt. In another of Chilton’s themes, the aliens are essentially peaceful, they abduct humans, but do not harm them. Now he invades Earth, not as a hostile act, but to save it from human self-destruction, ‘I offer the Earth the benefit of a million years of bitter experience’. Finally, taking up orbit around Earth, Morgan’s message is acted upon. All TV transmissions are killed. With his plan sabotaged, the Martian allows those ‘conditioned men’ who wish, to return to Earth, while he redirects his fleet away from Earth, to seek an alternative new home-world in the Proxima Centauri system. End.

‘WELCOME TO TOMORROW’S WORLD! ANYTHING

CAN HAPPEN HERE! AND EVERYTHING HAPPENS FAST!’

Apparently there were approaches from the ‘Hammer’ studios about a movie. After all, they were doing great box-office with their TV spin-offs from the ‘Quatermass’ series. Director David Lean also expressed an interest in a big-screen adaptation. Meanwhile – inevitably there were novelisations based around the radio scripts. ‘Journey Into Space’ (1954) was the first novel Chilton had attempted, followed by ‘The Red Planet’ (1956), and ‘The World In Peril’ (1960). But instead it was to be in another, more modest visual medium that ‘Jet Morgan’s exploits would continue, with Chilton taking a hands-on approach to a series of picture-strip adventure serials in ‘Express Weekly’. A cover-splash announcing ‘Inside – JET MORGAN, See Him For The First Time! His Latest Journey Into Space!’

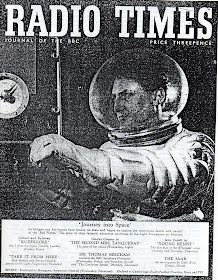

The comic was a title with a complex history. Originally launched from the Beaverbrook stable as ‘Junior Express’ from 4th September 1954, then ‘Junior Express Weekly’, it was designed to be a children’s version of the ‘Daily Express’, leading off with its own parallel adaptation of ‘Jeff Hawke: Space Rider’, a weekly comics-version of the daily newspaper strip, illustrated in simple red-&-black by talented Italian artist Ferdinando Tacconi. When ‘Express’ was relaunched 18th February 1956, as a glossy tabloid rival to ‘Eagle’ with the same rich gravure colour-spreads, ‘Jeff Hawke’ was expanded to fill the full-colour centre-spread. When the ‘First Citizen Of The Space Age’ was dropped, radio-star ‘Jet Morgan’ promptly planted his space-boots into the vacated page 8-9 spread, retaining many of the elements of the strip it replaced. Not only the identical pages and the same extraterrestrial location, but artist Tacconi too. In truth, he faced something of a conundrum. If his illustrations of the characters of Jet and his companions tend to seem interchangeable, that could be less due to the admitted limitations of his art-style, and more to do with their transition from radio. Later adaptations of TV Sci-Fi to picture-strip format, from ‘Doctor Who’ through to ‘Thunderbirds’, had the advantage of matching familiar visual expectations. Radio was different. ‘Radio Times’ ran photo-features of the ‘Journey Into Space’ stars, sometimes mocked-up in unconvincing space-suits, but listeners had already built up their own unique ideas of what Jet and his crew looked like, based on their voices. Presenting Tacconi with an impossible challenge. Although his drawings were modelled on the actors voicing the parts, those actors, of course, remained unseen by their audience. According to the novels Jet sports an unruly mop of black hair from which he gained his nickname. So he’s portrayed as brunette with a Billy Fury slick. Hatchet-faced Doc is auburn-haired, Mitch is tall, slim, ‘sun-tanned’ and leathery-faced, while stocky Lemmy sports a blonde quiff. Tacconi even includes Chilton himself as model for the giant Martian.

The first strip adaptation rocketed across the full-colour centre-pages of ‘Express No.84’ (28 April 1956), and it forms a direct sequel to ‘The World In Peril’. Entitled ‘Planet Of Fear’, the serial is set in the far-distant future of 1976, with Jet and his regular team leaving the Lunar ‘Bay of Rainbows’ Base bound for Mars, only to be inexplicably snatched into deep space. ‘The months pass, with the ship and its gallant crew hurtling through the void into the unknown’. Whereas the radio serials were high on dialogue, overcoming adversaries more by wit than force of arms, now they arrive at a planet called Gamma in the Alpha Centauri system where they encounter a curious blend of dinosaurs, hostile Flying Saucers armed with heat-rays, man-eating trees, and primitive Ape-Men (‘to think we travelled four light years through space only to end up as a monkey’s lunch’ wise-cracks Lemmy). They discover that two rival cities are competing for dominance of the planet – the northern city of Kaphos ruled by the childlike Kronos and his Faceless slave-hunters from dying neighbouring planet Beta, and, more curiously, the southern hemisphere city of Terra occupied by the peaceful last Martian giant and the descendents of his conditioned Earth-men! Through some relativistic time-loop the same Martian spheres that Jet had persuaded to leave the solar system in 1971, had arrived on Gamma a century ago!

Would this story have formed the basis for a fourth radio serial? Well, the BBC sound-effects department would have been more than equal to the task! As it is, the serial was followed by ‘Shadow Over Britain’ in which, eighteen-months after leaving Earth, ‘the Discovery’ returns through the time barrier to discover the moon colony in ruins and the Dartmoor Rocket Base abandoned. ‘This is a queer business’ muses Jet as they head through a seemingly deserted countryside affected by strange piercing sounds, to eventually arrive at London Space HQ. Picked up as looters they learn that only a few thousand people remain in Britain, most of them either police or thieves, and that ‘mankind and all civilisation are about to come to an end’. Periodic attacks of focused radiation that are disrupting power supplies and inducing sickness are traced to the lunar Plato crater. Whisked to the provisional commonwealth government in Montreal, and then to the moon itself, the quartet survive attacks by mysterious spaceships, to discover a domed base within Plato complete with a lake, irrigated fields, and hostile gunmen. The villain responsible is a James Bond-style evil megalomaniac called The Overlord, who harbours plans for world domination. He is assisted by an alien called Dr Smith, the ‘only survivor of a colony of space beings found on the moon by the Overlord, and wiped out’. Smith brainwashes Jet by grafting artificial memories that lead him to believe his friends are dead, supposedly killed by evil men who control Earth. As the Overlord prepares his invasion fleet – assisted by Jet, his three very-much-alive pals kidnap blue-faced Dr Smith and use him to sabotage the base’s Water Generating Plant, which also provides fuel for the spaceships. With Jet revived, they also release and arm the Overlord’s abducted African slaves. In the battle that ensues the would-be dictator is killed when the lethal beam from a ray-gun he directs at Jet’s stronghold ricochets back at him. Despite the furious action it’s a less-than entirely successful tale, perhaps let down by art-changes as Tacconi was replaced by ‘Dan Dare’ alumni Bruce Cornwell, then by Terence Patrick. Born in 1929, Patrick had already worked for Scion publishing and for DC Thomson’s ‘Black Sapper’ tales of an arch-criminal who uses a subterranean boring-machine to commit dastardly crimes in ‘Hotspur’, he later illustrated SF characters ‘Space Patrol’ for ‘Beezer’ and ‘Starhawk’ for ‘Spike’. He retired in 1991, and died soon after.

In the meantime, he assumed full art-duties for Jet Morgan’s ‘The World Next Door’ (nine episodes from 10th August to 5 October 1957), when inexplicably a second Earth appears in the sky on an impending planetary collision-course. Opening with a highly topical Cold War confrontation, the three big space-faring powers are compelled to draw together ‘as a token of the world’s unity in the face of a shared danger’. But it’s not the Americans or the Soviets, but British spaceman Jet Morgan who is first to respond. It’s an intriguing SF concept, let down only slightly by the uneven plotting and occasionally poor visualisation. Jet discovers that time-rays used in a future global war have dislodged the planet, so that ‘buildings of many years before began to reappear where they had once stood, strange people of your century and centuries before appeared and disappeared’. Also, on future-Earth, Ireland has inexplicably disappeared! Descending through the atmosphere of the planetary intruder Jet encounters a 1917 bi-plane, and on the surface he’s attacked by a Crimean-war era cavalry lancer. He learns that following the ‘hot sun famine’ when ‘millions left Earth for Mars, never to return’, future-Earth of 2,200 is ruled from Tibet by a Lama who lives in a globe that gives him eternal life. Defying the Lama, Jet liberates imprisoned scientists from their subterranean prison complex, and they use the House of Commons as a base for transferring Earth-2 back to its correct position in space-time. ‘So finally, the world of the future returns to its own time…’ runs the commentary-box, ‘Jet, Lemmy, Doc and Mitch can be satisfied that another mission is completed.’ ‘Blimey Jet’ groans Lemmy less enthusiastically, ‘we’re not going looking for more trouble are we?’ But no, for ‘Express Weekly’, there were to be no further ‘Jet Morgan’ exploits.

Chilton is credited as providing all the scripts (although his input to ‘The World Next Door’ was probably minimal), including those for two additional slight shorts featured in the hardback ‘Express Annuals’. ‘Jet Morgan & The Space Pirates’ in which the heroes pursue bad guys on the dark side of the moon. And ‘Jet Morgan & The Space Castaway’ set in 1980, with Bruce Cornwell’s art showing Jet pursuing interplanetary diamond-thieves through space until they burn up on re-entry ‘leaving trails like shooting stars’ in the night sky. Despite the apparent demise of his most famous creation, Chilton’s career remained active at Dan Dare’s Hulton Press home. He’d already originated western hero Jeff Arnold as the radio star of ‘Riders of the Range’ as early as 13th January 1949. He gleefully recalled how, following the early success of the series he was invited to the USA, and made ‘honorary Marshal of Tombstone and an honorary member of an Indian tribe’. In the days before pre-recording, the shows went out live, faults and all, with Alan Keith as Billy The Kid, and announcer Paul Carpenter declaring ‘Boys, we’re saved, here comes a horde of hearses (herd of horses)!’ Adapting it into a strip for ‘Eagle No.37’ (22 December 1950), his adventures in the old west enthralled readers until 1962. Meanwhile ‘Express’ continued without ‘Jet Morgan’. Ron Embleton’s beautifully-crafted artwork for ‘Wulf The Briton’ was deservedly promoted to cover star status, scripted by Michael J Butterworth it took Wulf ‘Out of the Desperate Days of Ancient Rome’ into a series of exploits across the Roman empire. ‘Express’ swallowed up the short-lived SF-weekly ‘Rocket’ in December 1956, and was then itself reborn into a new incarnation as ‘TV Express’ from 16th April 1960 after 212-issues. There were further annuals too, the 1960 edition led off with ‘Redskins Honour’, and included a Ron Embleton ‘Wulf’ tale, then the ‘TV Express 1961’ also featured an Embleton ‘Wulf’ strip, but by then, Jet Morgan was long gone.

Then, decades passed. Andrew Faulds quit outer-space to became a Labour MP, inspired by meeting activist Paul Robeson. Although his acting career continued, as part of Ken Russell’s company, he sat in the same House of Commons where the twenty-third century electronic ‘Controller’ would be sited in the Jet Morgan story, serving as MP for Smethwick from 1966 until he retired in 1997, three years before he died. Among Guy Kingsley-Poynter’s other acting achievements was providing the narrator voice-over from the Harrison Marks nudie-exploitation film ‘Naked As Nature Intended’ (1961). Alfie Bass, already held in national affection through ITV’s ‘The Army Game’ and ‘Bootsy & Snudge’, went on to acclaim in the West End production of ‘Fiddler On The Roof’. After retiring from radio, Chilton could be found conducting tourists on the Original London Walks trails. Yet he continued to be ‘regarded affectionately by older British listeners’, according to SF academic David Pringle. The generation that had been thrilled by the Jet Morgan tales as children grew up, and they had not forgotten. Ultimately the BBC asked Chilton to pick up the threads of the ‘Journey Into Space’ mythos as part of a special Radio 4 ‘Saturday Night Theatre’ SF Season. The result was ‘Return From Mars’ in which the adventurers return to Earth after being adrift in space, presumed dead, for the intervening thirty years. Jet makes up for lost time by having an affair with one of the locals. A second special – ‘Frozen In Time’ followed, leaping ahead to 2013 with the crew of the ‘Ares’ again reviving from cryogenic suspension – except for Jet himself, whose pod failed. He’d been awake all the time, and is now seventy-two years old! The space-farers find themselves considered anachronisms, but affect a rescue in a Mars-based mining-operation. Reception was mixed. To David Pringle, Chilton ‘had not kept up with developments in the genre, and his work now seemed woefully dated’. More recently ‘The Host’, on Radio 4 in 2009, became the first Jet Morgan story not written by Charles Chilton, although he did contribute a few words at the close. It utilises the same idea of Jet and his crew coming out of cryogenic-sleep into new situations, but involves a greater higher-tech computer/DNA awareness than the ‘one million mekatones’ contrived tech-speak used previously. Radio 7 re-ran a tie-in interview with Chilton, originally recorded with John Dunn for Radio Two and announced as ‘Charles Chilton for the low-brow bits’, on the occasion of his seventy-fifth birthday (1992) – in which he admitted that although he wrote SF, he never actually read any of it. Unlike Jet himself, who reads the exploits of his ‘literary predecessors’ in HG Wells’ ‘The First Men In The Moon’ out aloud to his companions as they are marooned on the lunar Bay of Rainbows. Then, in ‘The World Next Door’ where Lemmy admonishes ‘Hey Jet, Take it easy! You’ve been reading too much Science Fiction!’ And the fact that Chilton incorporates ‘The Rebel Song’ based on Robert Heinlein’s ‘Rhysling’ poems from ‘The Green Hills Of Earth’ into the first radio serial (a song written for Heinlein by Clark Harrington, who extended Chilton permission for its re-use)! There were also celebration repeat-instalments of ‘Journey Into Space’ and Chilton’s later ‘Space Force’ tales. It seems that 1950’s Space Heroes never die, and show few signs of fading away either.

Former London-mayor Ken Livingstone told the ‘Observer’ that ‘my childhood passion was natural history and my heroes were Dan Dare and Jet Morgan (who was played by Andrew Faulds MP) in ‘Journey Into Space’. And Colin Pillinger, the British planetary scientist responsible for the failed ‘Beagle-2’ Mars-probe recalls ‘my first encounter with space was the radio series ‘Journey Into Space’ in 1954, about Britain being the first to land on the Moon’. Fortunately Jet Morgan’s projects yielded more positive results on the Red Planet than Pillinger’s did. And Venus remained unvisited. An exclusion zone set aside for Dan Dare’s exploits perhaps?

‘JOURNEYS INTO SPACE’

JET MORGAN ON RADIO

‘Journey Into Space’ (21 September 1953 to 19 January 1954 – 18 episodes.) Written by Charles Chilton. Jet Morgan: Andrew Faulds. Doc Matthews: Guy Kingsley-Poynter. Stephen ‘Mitch’ Mitchell: Bruce Beeby (2-6) & Don Sharp (7-18). Lemuel ‘Lemmy’ Barnet: David Kossoff. Plus Deryck Guyler as the ‘Time-Traveller Voice’, and David Jacobs. Set in 1965

‘Operation Luna’ (partial remake of first story, minus first four parts, 26 March 1958 to 18 June 1958 – 13 episodes. Re-broadcast Radio 2 1989. Issued as 7-CD set by BBC Audiobooks 5 July 2004) Written by Charles Chilton. Jet Morgan: Andrew Faulds. Doc Matthews: Guy Kingsley-Poynter. Stephen ‘Mitch’ Mitchell: David Williams. Lemuel ‘Lemmy’ Barnet: Alfie Bass

‘The Red Planet’ (6 September 1954 – 17 January 1955 – 20 episodes. Re-broadcast Radio 2 1990. Issued as 10-CD set by BBC Audiobooks 3 January 2005) Written by Charles Chilton. Jet Morgan: Andrew Faulds. Doc Matthews: Guy Kingsley-Poynter. Stephen ‘Mitch’ Mitchell: Bruce Beeby. Lemuel ‘Lemmy’ Barnet: David Kossoff. Plus David Jacobs as ‘Frank Rogers’, Don Sharp as ‘Sam’, and Miriam Karlin as Lemmy’s MumSet in April 1971

‘The World In Peril’ (26 September 1955 – 6 February 1956 – 20 episodes. Re-broadcast Radio 2 1991. Issued as 4-cassette set by BBC Worldwide Ltd, 1998, & download October 2006) Written by Charles Chilton. Jet Morgan: Andrew Faulds. Doc Matthews: Guy Kingsley-Poynter. Stephen ‘Mitch’ Mitchell: Don Sharp. Lemuel ‘Lemmy’ Barnet: Alfie Bass. Plus David Jacobs as ‘Frank Rogers’. Start-date is 15 April 1972

‘The Return From Mars’ (Radio 4, Saturday 7 March 1981, one 90-minute episode. Issued as two-cassette set by BBC Worldwide Ltd, 2000) Written by Charles Chilton. Jet Morgan: John Pullen. Doc Matthews: Ed Bishop. Stephen ‘Mitch’ Mitchell: Nigel Graham. Lemuel ‘Lemmy’ Barnet: Anthony Hall

‘Frozen In Time’ (Radio 4, 12 April 2008, one 60-minute episode) Written by Charles Chilton. Director: Glyn Dearman. Jet Morgan: David Jacobs. Doc Matthews: Alan Marriott. Stephen ‘Mitch’ Mitchell: Michael Beckley. Lemuel ‘Lemmy’ Barnet: Chris Moran

‘The Host’ (Radio 4, 27 June 2009, one 60-minute episode) Writer: Julian Simpson. Jet Morgan: Toby Stephens. Doc Matthews: Alan Marriott. Stephen ‘Mitch’ Mitchell: Jot Davies. Lemuel ‘Lemmy’ Barnet: Chris Pavlo. Plus David Jacobs as ‘The Host’. Charles Chilton – then aged 93, reads the closing credits

JET MORGAN IN BOOKS

‘Journey To The Moon’ aka ‘Journey Into Space’ by Charles Chilton (1954, Herbert Jenkins hardback at 9s 6d, with dust-jacket by Ron Jobson – who had illustrated the ‘Space Kingley’ annuals / 1958, Pan paperback at two shillings, cover by Gordon / 1963, reissue by Digit, the paperback division of Brown Watson Ltd )

‘The Red Planet’ (1956) by Charles Chilton (1956, Herbert Jenkins hardback at 10s 6d, dust-jacket by Ron Jobson / 1960, Pan paperback / 1963, Digit paperback)

‘The World In Peril’ by Charles Chilton. (1960, Herbert Jenkins hardback / 1962, Pan paperback)

‘Great Stories Of The Wild West’ Annual-style non-space-travel book by Charles Chilton

JET MORGAN PICTURE-STRIPS

‘Jet Morgan in: Planet Of Fear’ ‘Express No.84’ (from 28 April – 29 December 1956, 35 episodes), reprinted in ‘Spaceship Away no.7- ’ Script: Charles Chilton Art: Ferdinando Tacconi

‘Jet Morgan in: Shadow Over Britain’ ‘Express no.120’ (5 January – 3 August 1957, 31 episodes) Script: Charles Chilton Art: Ferdinando Tacconi From March 1957 Bruce Cornwell assumes art. From April 1957 Terence Patrick assumes art

‘The World Next Door: With Jet Morgan’ (‘Express’ Nine parts from 10th August to 5th October 1957) Script: Charles Chilton (credited) Art: Terence Patrick. The people of World-2 ‘Britt’ are identically-masked, according to social status

‘Jet Morgan & The Space Pirates’ (‘Express Annual No.1, publ September 1956’) Script: Charles Chilton Art: Tacconi. Originally done in black-+-white, later coloured by John Ridgway. Jet operates from International Space Flight HQ, tracking shipments of Lunar plutonium

‘Jet Morgan & The Space Castaway’ (‘Express Annual No.2, September 1957’) Script: Charles Chilton Art: Bruce Cornwell. ‘The year is 1980. A ship of the International Spaceways Police Force is on a routine trip between Earth and the Moon’. Jet and his team track Moon Freighter X247 to the far side of the Moon

THE MANY WORLDS OF CHARLES CHILTON

‘Space Force’ (4 April 1984) – six episodes & ‘Space Force 2’ (13 May 1985) – six episodes, scripted by Charles Chilton, originally intended as a radio sequel to ‘The World In Peril’, but re-cast with new characters. Chilton was also celebrated as the creator of the long-running radio Western series ‘Riders Of The Range’ (from 13 January 1949) which featured an appearance by ‘Doc’ Guy Kingsley-Poynter. He was also instrumental in radio programmes such as ‘The Blue & The Grey’ – a musical documentary on the US Civil War which featured ‘Journey Into Space’ musical director Van Phillips, ‘The Marie Lloyd Story’, ‘Ballad History Of Samuel Pepys’ and ‘Songs That Made The Halls’, as well as the BBC-TV comedy series ‘Dig This Rhubarb’ with Anthony Jay (October 1963-April 1964) and Michael Bentine’s ‘It’s A Square World’. His ‘The Long Long Trail’ (1962) – a radio First World War musical documentary was first adapted into the Joan Littlewood stage-show (1963) and then film ‘Oh, What A Lovely War’ (1969) for which Chilton was credited as producer. In 1992 he scripted ‘BH92: The BBC Radio Show’ stage presentation (Saturday 22 August-Sunday 4 October) at Broadcasting House, he told ‘Radio Times’ ‘the brief they gave me was to encapsulate the highlights of the Corporation’s seventy-year history in a half-hour show. If I’d realised what I was taking on, I probably wouldn’t have said ‘yes’ so readily!’

Charles Chilton: ‘He denies that he is a legend. But he will be…’

Published in:

‘JEFF HAWKE’S COSMOS Vol.6 No.1’ (UK – May 2010)

A really fasinating read of the exploits of Jet and Crew, along with a very good account of Charles chilton.

ReplyDeleteWell Done

godlee19242@yahoo.co.uk

Order a Sparkling White Smiles Custom Teeth Whitening System online and get BIG SAVINGS!

ReplyDelete* Up to 10 shades whiter in days!

* Results Are Guaranteed.

* Better than your dentist, for a fraction of the cost.

* Same Teeth Whitening Gel as dentists use.

I just want to say this is extremely useful, thanks for giving me the time to make this.

ReplyDeleteBoom Recorder Pro Crack

SmartSVN Pro Crack

Sounds Mars Crack

Antares AVOX Crack

LUXONIX Purity Crack