HOLGER CZUKAY:

CAN... HOW TO

RECOGNISE

DECADENT MUSIC

Can are the group who form the sonic link between Stockhausen

and Hip-Hop.

They were Germany’s most seminal subversive

audio terrorists of the 1970’s,

and their influence lives in the work

of Radiohead, Leftfield and beyond.

Now ex-Can Holger Czukay

talks about Jah Wobble’s ‘hundred hands’,

about why Old Movies

are better than New Movies,

and his surprising debt

to WC Fields and Charlie Chaplin...

HOW TO RECOGNISE

DECADENT MUSIC

-

1: SNAKE-CHARMING

IN THE COOL

‘I love concentrating. Listening to music makes it a real event, an event in time. How time is condensed. How it makes something with you. People call it magic. Whatever that is. But actually it is the flowing of time. Music is time. Somehow it is lived time. Or condensed time...’ Holger Czukay deals in scrapbooks of sound. He’s possibly some kind of manic genius. The Mad Scientist mixing and matching racks and retorts of tapes, wires, and odd chemicals of alchemaic noise into a phantasmagoria of aural sorcery. He’s sat in front of me now, here in London’s EMI House. And he looks the part. Walrus-bewhiskered, absent-minded, undeniably Germanic. He emphasises in huge surges of energy that assault the listener, while defusing tension with mischievous sparks of Einsteinian eccentricity. Sometimes he seems to be sending you up. But it’s such a vastly entertaining experience you enjoy the ride.

We were talking – at some considerable length, during an extended promotional trip undertaken to Thatcher’s blighted isle, doing press for his album ‘Der Osten Ist Rot’ (1984), issued through a hook-up with Virgin. And it is a CD that remains – or in his words ‘survives’, as an idiosyncratic tour de force of oddities running from the title-piece, a seven-minute cut-up reworking of the Chinese National Anthem (“The East Is Red”), through to the concurrent novelty single – “The Photo Song”. But his work simultaneously extends out into a variety of other avant garde settings too, with Brian Eno (as ‘Cluster’) and the Eurythmics. He also contributes to David Sylvian’s ‘Plight And Premonition’ (March 1988) album – an association growing out of their mutual involvement with producer Conny Plank. While Holger’s partnership with equally off-the-wall bassist Jah Wobble – who he pronounces ‘Shah Vo-Bell’, is ongoing They turn up on each others records. Czukay guesting on Wobble’s critically acclaimed ‘Snake Charmer’ (1983) mini-album, a favour Wobble returns by contributing to Czukay’s entrancing ‘On The Way To The Peak Of The Normal’.

So, taking this cue from this discussion of New Music, what is Wobble like to work with? ‘He’s playing bass with two hands. OK?’ OK. ‘But he’s also playing with his whole body. And when he’s sitting at the recording or mixing desk he will have MORE than two hands. And he knows it. He’s well aware of it.’ Czukay deals in the technology of magic. Before commencing work on his ‘...Peak Of The Normal’ album he even rebuilt his own Inner Space studio in Cologne, re-rigging and customising it to by hand to his own rigorous requirements. For the studio is part of his art. It allows him to edit, arrange, and re-arrange sound. And it is here that recordings made over a two-year period can be compressed down into just eighteen minutes of completed product. With multi-tracking and dubbing, the studio can give a musician the ability to operate on a multitude of levels simultaneously – giving him ‘more than two hands’.

HOW TO RECOGNISE

DECADENT MUSIC

-

2: REMEMBERING

FUTURE DAYS

‘To destroy something is the beginning of building up something. If you put these two aspects together then you make an interesting act, ya? That is exactly the quality of Can in those early days.’ Its energy was based on the internal tensions thrown up by conflicts in style and ideas, and the compression necessary to unite them. ‘Ya, so Can’s only chance was that everybody would reduce themselves as far as they could with what they did? Otherwise it would just be a group of four egos, and no-one likes to listen to that.’ But even after the demise of Can – alongside people like Conny Plank, drummer Jaki Liebezeit gets to play on ‘Der Osten Ist Rot’, so if the old associations persist, can Can really be said to be truly dead? ‘No. I wouldn’t say that. We still work together. But not as Can. Jaki said ‘Can has made a kind of cell division’ – do you say that?’ A cellular division, yes. ‘That is what Can did. And for me this is what life is. A group one day gets born, it’s an organism, really an organism. One hand works with the other hand – ‘hand in hand’ as we say in Germany. So OK, Can made something important – I think. And then, after a while – it died.’

So what category would you place your music in now? He explodes – ‘categories don’t mean anything. I say – just use EVERYTHING! There is NOTHING that should prohibit you. You contribute whatever your spiritual power is.’

HOW TO RECOGNISE

DECADENT MUSIC

-

3: CHARLIE CHAPLIN

& W.C. FIELDS

The early 1980’s was a period generally unsympathetic to ‘legends’. But Can proved to be the exception. When John Lydon’s Public Image Ltd first issued their dense barrages of sound, it set reviewers scuttling back to early Can as the only place to find suitable comparisons. And the German band began to be re-assessed and fully credited with the significance of their torturous innovation. In fact, throughout the 1980’s Can’s legacy in general – and Czukay’s contribution in particular, was regarded with something approaching supernatural awe by experimentalist electro-industrial musicians such as Cabaret Voltaire, Throbbing Gristle and Clock DVA. The Fall even issued a single – “I Am Damo Suzuki” as a tribute to Can’s one-time vocalist (who once claimed he sang in a ‘Stone-Age language’). But even within the confines of Can, Czukay was an extremist. Richard H Kirk (of Cabaret Voltaire) once confided to me that ‘we really respect Can, and particularly Holger Czukay’s stuff. When we saw them working live he’d actually stopped playing bass with them. That was when he was using old radio sets on stage. He was surrounded by a mass of tape recorders and radio receivers, just standing there in the middle of all this equipment. And it was nice to see somebody using that solely as their instrument.’

It was into this kind of near-reverential atmosphere that ‘Der Osten Ist Rot’, and Czukay’s related projects – including his idiosyncratic stop-gap single “Cool In The Pool” c/w “Oh Lord, Give Us More Money” (consisting of edited extracts from his second solo album, ‘Movies’, 1979) attracted such positive attention and reams of good reviews. Later, in the 1990’s, it would be Radiohead (particularly on their 2000 ‘Kid A’ project) and Leftfield who would be speaking of their respect for the example and inspiration provided by Can. And this is even more exceptional, because Czukay’s celebrity value throughout this period was maintained without any live promotion whatever. ‘I was on stage with Can for ten years’ he confesses. ‘And sometimes I felt, when I was on stage, that I was not always ready for it. You feel responsible after a while in front of an audience. And I thought ‘I am not ready to feel that responsibility again’. Therefore I wanted to explore the media first, and find out about myself. When I’m ready for it, I’ll go back on stage again. And when I do go back on stage I know it will be somehow like the early Can days.’

Of course, the technology for making films is far more accessible now than it was, say, even twenty years ago. ‘Yes, but think about how it was FIFTY years ago. Remember when you see an old Hollywood movie of the 1930s or the 1940s, that the film media was at that time not highly developed. It was ‘unperfect’. They had to be very skilful with everything that they did. No zooms for example – how wonderful! They had to move the cameras, and they were big cameras. But look at how the picture is coming out on the screen. It’s not just simply ‘photographed’ or ‘filmed’, it is painted onto the celluloid. Those people had to put so much into their work. Today, that spirit is gone. When I see modern Movies or television – they put the cameras on something, let’s say a street scene, a Volkswagen comes by and I switch off immediately. I say ‘thank you, a Volkswagen I have of my own’. Better I drive it or touch it, but I don’t want it on the screen. Then see how an old movie is done – how a car comes from off the camera and disappears. It is a real poem. It is this quality in the music that also sometimes gets lost.’

I studied WC Fields. I studied especially Charlie Chaplin at that time too, because I knew that he has this quality. These are the people who have everything in their own hands. Charlie Chaplin edited. He was standing behind the camera. He standing in front of the camera. He was writing the scripts and he was making the music. That is really something, I thought. To get that special quality out, you have to be those hundred hands. WC Fields is the same. He fascinates me. And it took me a long time until I understood why. Until I understood that quality of his. I didn’t understand it all in the beginning. But now I EAT HIM like crazy. I can watch his Movies – ‘Never Give A Sucker An Even Break’ (1941, Universal) I can see that 1000 times and laugh always about the same thing. And I say ‘why is it you’re able to laugh 1000 times at the same things?’ That is something where the humour goes beyond the joke. And that’s what I like to achieve in my music. Exactly that. That people can listen to it after twenty years, in the same way that I enjoy watching WC Fields. Because when you see a fascinating movie, you are banged on the screen. You don’t dare to look left or right. Whereas what you usually do when you listen to music is to use it as a background for all kinds of housework. That doesn’t happen when you watch a Movie. So I say ‘I make this kind of music where people LISTEN again’.’

Hey, I’m listening...

HOLGER CZUKAY:

THE CAN PROJECTS

Aug 1969 – ‘DELAY 1968’ 500 privately-pressed limited edition, officially released in 1981

May 1970 – ‘MONSTER MOVIE’ (UA) with vocalist Malcolm Mooney, includes ‘Father Cannot Yell’, ‘Outside My Door’ and 20-minute ‘You Doo Right’

Sept 1970 – ‘SOUNDTRACKS’ (UA) with Malcolm Mooney, includes ‘Mother Sky’, ‘Deadlock’

1972 – ‘EGE BAMYASI’ (UA) with ‘Spoon’ and ‘I’m So Green’

Jun 1973 – ‘FUTURE DAYS’ (UA) final album with Damo Suzuki, includes ‘Moonshake’ and ‘Spare A Light’

Nov 1974 – ‘SOON OVER BABALUMA’ (UA) with ‘Quantum Physics’ and ‘Chain Reaction’

Sept 1975 – ‘LANDED’ (Virgin) with ‘Hunters And Collectors’ and ‘Vernal Equinox’

Oct 1976 – ‘FLOW MOTION’ (Virgin) with ‘I Want More’ and ‘Smoke’, features Pink Floyd’s Dave Gilmour

May 1976 – ‘UN/LIMITED EDITION (EARLY RARE)’ (Caroline) compilation

Nov 1976 – ‘OPENER’ (Sunset) compilation of 1971-1974 period

Mar 1977 – ‘SAW DELIGHT’ (Virgin) with ‘Animal Waves’ and ‘Fly By Night’, features Rosko Gee and Reebop Kwaku formerly of Traffic

July 1978 – ‘OUT OF REACH’ (Harvest/ Lightning) with ‘Serpentine’ and ‘November’, Holger Czukay is not featured on this album

Oct 1981 – ‘INCANDESCENCE’ (Virgin) compilation

Oct 1978 – ‘CANNIBALISM’ (UA) compilation

Feb 1985 – ‘INNER SPACE’ (Harvest/ Lightning) re-issue of 1979’s ‘CAN’ LP with Holger Czukay credited as ‘tape editing’ only, includes ‘All Gates Open’, ‘Safe’, ‘Sunday Jam’, ‘Sodom’, ‘Aspectacle’

Oct 1989 – ‘RITE TIME’ (Mercury) re-formed original line-up complete with Malcolm Mooney, includes ‘The Without Law Man’ and ‘Like A New Child’

1993 – ‘CANNIBALISM 2’

HOLGER CZUKAY:

THE SOLO PROJECTS

1968 – ‘CANAXIS 5’ (Factory) as by HOLGER CZUKAY WITH ROLF DAMMERS, other Can members contributing

Jan 1979 – ‘MOVIES’ (Electrola, EMI) as by HOLGER CZUKAY, features singles tracks ‘Cool In The Pool’, ‘Oh Lord Give Us More Money’ plus ‘Persian Love’ and ‘Hollywood Symphony’. Features Rebop Kwaku Baah (organ), Jaki Liebezeit (drums), Michael Karoli (guitar) and Irmin Schmidt (grand piano). Bonus ‘Cool In The Pool’ instrumental on 2006 CD re-issue

1981 – ‘PHEW’ (Pass) Holger Czukay and Jaki Liebezeit teamed with vocalist PHEW

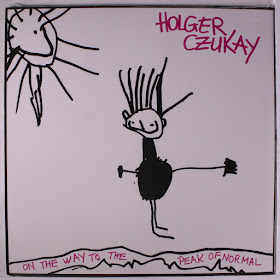

Feb 1981 – ‘ON THE WAY TO THE PEAK OF THE NORMAL’ (Electrola, EMI), features ‘Ode To Perfume’ (18-minutes), ‘On The Way To The Peak Of The Normal’ (with Harry Rag), ‘Witches Multiplication Table’, ‘Two-Bass Shuffle’, ‘Hiss ‘n’ Listen’ (with Jah Wobble), with Jaki Liebezeit (drums), Conny Plank (synthesiser violin)

1982 – ‘FULL CIRCLE’ (Virgin) as by HOLGER CZUKAY, JAKI LIEBEZEIT & JAH WOBBLE

Oct 1983 – ‘SNAKE CHARMER’ (EP, Island) as by HOLGER CZUKAY, JAH WOBBLE & THE EDGE

May 1984 – ‘DER OSTEN IST ROT’ (Virgin) as by HOLGER CZUKAY, features ‘The Photo Song’, ‘Das Massenmedium’, ‘Collage’, ‘Michy’ and ‘Esperanto Socialiste’

Jan 1987 – ‘ROME REMAINS ROME’ (Virgin) features ‘Sudentenland’, ‘Perfect World’ and ‘Blessed Easter’ which controversially mixes a cut-up of a Papal speech

1989 – ‘FLUX AND MUTABILITY’ with DAVID SYLVIAN

Jan 1991 – ‘RADIO WAVE SURFER’ (Virgin) with Sheldon Angel (vocals), Michael Karoli (gtr) Jaki Liebezeit (drs), features ‘Voice Of Bulgaria’, ‘We Can Fight All Night’ and ‘I Got Weird Dreams’

1993 – ‘MOVING PICTURES’ (Mute Records) with U-She vocals on ‘Dark Moon’ and ‘Longing For Daydreams’, Romie Singh vocals on ‘All Night Long’ and ‘Rhythms Of A Secret Life’, plus ‘Radio In An Hourglass’ and ‘Floatspace’

1997 – ‘CLASH’ (Sideburn) collaboration with DR WALKER

1999 – ‘GOOD MORNING STORY’ (Tone Casualties) with U-She vocals on ‘Invisible Man’, ‘Atlantis’, ‘Mirage’, ‘World Of The Universe’, remastered and expanded 2006

June 2000 – ‘LA LUNA’ one extended electronic gamelan track, remastered and expanded 2007

2001 – ‘LINEAR CITY’ (Dignose DIG002) with ‘Africana’, ‘Echogirl’, ‘Ten Steps To Heaven’ (23:02-minutes), ‘Africana Suselita’, remastered and remixed 2006

2015 – ‘ELEVEN YEARS INNERSPACE’ (Grönland Records LPGRON143) with ‘In-Between’, ‘Secret Of My Life’, ‘My Can Axis’, ‘My Can Revolt’, ‘A Maiden’s Dream’, ‘Breathtaking’

Also seek out:

‘THE CAN BOOK’ by PASCAL BUSSY &

ANDY HALL (SAF Publishing – Tel: 0181 904 6263)

Did you know that you can earn cash by locking special areas of your blog or website?

ReplyDeleteSimply join Mgcash and embed their content locking plugin.

Did you miss 'Plight & Premonition' in the collaborations section?

ReplyDelete