A SCIENCE FICTION DREAM:

‘DREAM’ MAGAZINE

At a late-eighties time when British SF was going through

something of an identity crisis, the neat semi-prozine ‘Dream’

proved to be a healing force, reconciling old and new,

tradition with innovation, across twenty-nine fine issues.

Andrew Darlington traces its history

The pensive robot sits on the edge of the Moon’s rim, in an attitude recalling Auguste Rodin’s The Thinker. Immersed in electronic dreams, it ponders the conundrums of Life, the Universe And Everything. The image – with variations, was used for the later covers of

‘Dream’. At a late-eighties time when British SF itself was going through something of an identity-crisis quandary, this neat semi-prozine proved to be a healing force, reconciling old and new, tradition with innovation. It looked back over its shoulder to the simpler John Carnell period of

‘New Worlds’ by publishing new work by its respected writers ER James and Sydney J Bounds. While simultaneously turning its fictional gaze to the future with early tales from Stephen Baxter and Peter F Hamilton, who were yet to make their massive mark on the genre.

One of the most consistently inventive and entertaining writers currently at work within the genre, Stephen Baxter’s fiction retains the ability to re-charge that SF ‘Sense Of Wonder’ with its immense sweeps through time and universes. Yet he started out more modestly. He entered

‘Dream’ with “The Bark Spaceship” (November 1987, no.14), published as by ‘SM Baxter’, at a time when he’d only recently debuted in

‘Interzone no.19’ with “The Xeelee Flower” (Spring 1987). Then his “The Eighth Room” was featured in

‘Dream no.20’ (Summer 1989), a story that already displays all the classic wide-screen SF elements in a concentrated form, with Teal as the young discontented rebel, impatient with the repressive restrictions of his teepee community. As the seeker after truth he becomes part of a trope already familiar from characters such as Alvin in AC Clarke’s

‘The City And The Stars’ or the thief in Walter M Miller’s “Big Joe And The Nth Generation”, a protagonist who strikes a sympathetic chord with the kind of adolescent misfits who are drawn to SF. For Teal, Home is linked to Shell by a slender sky-line. Although exiled, with the help of sympathetic grandfather Allel, he searches through blizzards for the secret of the world, accompanied only by his genetically-bred mummy-cow companion Orange, whose ‘song’ leads them to the dimensional-maze cube that allows him a glimpse of the stars beyond the protective shell in which the world is isolated. For

‘Dream’ it is one of a number of contributions, a further Xeelee story – “The Tyranny Of Heaven” follows in no.24 (Summer 1990).

While, although Peter F Hamilton – born 2 March 1960, made his first sale – “Deathday”, to Horror glossy

‘Fear Magazine’ (no.26, February 1991), he’d already been strongly featured in

‘Dream’ from “Bodywork” (September 1990, no.25). In

‘Dream no.28’ his “The Seer Of Souls” takes an uncharacteristic trip into the louche and effete realm of art with vampire art-dealer Tobias hoarding lifetimes of old masters to barter onto the market when he feels the time is right, speaking fluently of Goya and Picasso. There’s sycophants and devoted acolytes, with conjectured new sculptural forms in ‘essence nuroplaque cells’, all conveyed in rich descriptive passages, ‘Tobias saw the souls of the city as a galaxy of red dwarf stars. A glory nebula, pulsing with bright organic energy, alive and expanding.’ It’s as though he’s intent on impressing the reader, by also playfully suggesting ‘Hoyle’s theories as the explanation to their (vampire’s) condition. A space-born virus from ancient comets, a product of evolution hundreds of millions of years older than Earth’s.’

If the story is an unusual entry in his bibliography, Hamilton’s “Major’s Children” (in no.27) is more recognisably located within his hard-SF style with starship ‘Voidhawk’ – illustrated in Alan Hunter’s sympathetic artwork with its ‘thermo-dump panels’ extended like ‘sprouting silver dragonfly wings’, as it emerges from ‘her jump singularity’s pseudo-boundary four-million kilometres’ from Ladell, planet-sized moon of gas-giant Major of an insignificant G3 primary star. Kendal is a charter-pilot taking bereaved Gilbert and his seventeen-year-old daughter Jannine to the world where life-forms exist on a nine-year cycle before being killed off by Rama storms set up by unique planetary alignments. The wise native Ly-Cilph avoid this periodic extermination by a form of ‘ascension’ to spirit-form, a metamorphosis through which Gilbert hopes to be reunited with Kirsten, his dead wife. It is a tight well-wrought story. Yet from such modest beginnings his ‘The Night’s Dawn Trilogy’, the ‘Void Trilogy’ and the ‘Commonwealth Saga’ would establish him as the leading current exponent of galaxy-spanning Space Opera. But for followers of his novels, the stories Peter Hamilton contributed to ‘Dream’ would prove an unexpected revelation.

Publisher and first editor Trevor Jones was ‘a firm believer in the value of storytelling and was a fan of the ‘New Worlds’ style of fiction under John Carnell’ according to SF historian Mike Ashley. ‘He felt that British SF had fallen victim to the New Wave and its aftermath and wanted to restore some traditional values whilst also recognizing new talent.’ In his own words, his intention had been to ‘start producing a ‘different’ type of SF magazine, one that represented and applauded the traditional values of good story-telling and lucid narrative that the overblown pseudo-literary and ‘experimental’ markets of that era seemed, in the main, not to offer.’ That ‘we want to work, together with our writers and readers, to change the perceptions of British magazine Science Fiction or the nineties.’ That he was able to bring this ambition together into twenty-nine regularly-spaced issues is no small achievement.

Both Sydney J Bounds and Earnest (ER) James had been a consistently active part of the pool of writers that Carnell drew upon with the confident expectation of strongly-plotted action tales with Outer Space settings. Both of them had fallen out of favour as SF evolved away from that style. But they embodied the ‘traditional values’ that Jones was seeking. Based in Kingston-upon-Thames, Bounds offered a number of fine tales to ‘Dream’, followed by James – a former postman living in the picturesque Yorkshire town of Skipton, who also seized upon the opportunity of reaching a new audience. While their story-telling skills remain as sharp as ever, both writers had impressively upgraded their styles to include the computer-tech paraphernalia of the new time. Set in October 2172, James’ “Second Century Koma” (‘Dream no.13’) has L-L’s (Long-Lifers) granted longevity by treatment in their mid-twenties, who begin to enter a coma-state prior to their two-hundredth birthdays. Is there a cellular life-limit for humans? No, it’s just information overload that needs a computer plug-in access to accommodate the additional data flow. Voted no.1 story in the issue, it was reprinted in the ‘A Book Of Dreams’ anthology (1990) edited by Trevor Jones and George P Townsend.

Above all, emerging writers need a reliable forum in which to experiment with their craft, measure it against their equally-struggling contemporaries, and exchange ideas in a sense of virtual community. Jones, in partnership with co-editor Townsend was able to provide this forum, fairly rapidly developed a growing stable of writers, numbering Gerry Connelly with “Draco” (January 1986, no.3) – his later story of a believed UFO abduction, “The Rzawicki Incident” (July 1987, no.12) was voted the all-time most popular story in ‘Dream’! There was also Peter T Garratt, who had debuted in ‘Interzone’ the year before, with “The Angel Of Destruction” (September 1986, no.7), Ian G Whates with “Flesh And Metal” (March 1987, no.10), and Keith Brooke with “The Fifth Freedom” (Winter 1988, no.18). As Mike Ashley points out, ‘most of these writers went on to establish themselves in ‘Interzone’ and elsewhere, but it was ‘Dream’ that gave them space to fledge.’

Not all of them went on to write more. There were also intriguing one-offs, author Marcin P Sexton who has a single entry in the ‘Internet Speculative Fiction Database’, which is “Reich” from ‘Dream no.21’ set during the Nazi occupation of vast tracts of Russian territory, with Carl Konigsberg answering a Top Secret communiqué from the Berlin Museum Of Anthropology to investigate alien remains discovered in a remote village of women. It’s an occult rewriting of history with the closing paragraph, ‘since the alien was delivered to be included in the Fuhrer’s own personal collection of curiosities, the Fuhrer’s mental state has worsened. It must be the pressure of the war. Today he declared war on America without reason, except to say he was destined to rule the world. Where will it end?’ Other writers, such as Jack Wainer – the pen-name used by David Bell of Melton Mowbray, had debuted in the ‘Thirtieth Pan Book Of Horror Stories’ (1989) followed by a dozen magazine appearances, which included the Living Doll ‘Chucky’ tale “Miss Blood” (‘Dream no.27’) in which the teenage protagonists appealingly role-play their fantasy lives of being artist and Rock star.

Wedged somewhere in-between there’s my own story “Matrix”, which had originally been sold to NEL’s ‘Science Fiction Monthly’, which folded before getting around to publishing it! Uncertain about the copyright situation I delayed resubmitting it elsewhere until I was reasonably sure there would be no negative consequences. Indeed, I received only positive feedback from its appearance it ‘Dream’. My next story – “The Carnivorous Land”, appeared in the second, and final issue, of ‘New Moon’, the ambitious sequel follow-up publication to ‘Dream’. Matched to line-illustrations of astonishing quality by the very talented Kevin Cullen, I’m proud of, and greatly value this association with the magazine.

For the artwork embraced the same wide diversity as its pool of writers, with work by the prolific Alan Hunter (19 February 1923-1 August 2012) who had been appearing regularly within the genre since his early 1950s covers and distinctive interiors for ‘Nebula’ and ‘New Worlds’ as well as for a host of fanzines for which he received little or no payment. His was an instantly recognisable style, with a near-woodcut quality that made him a familiar part of the scene, and there are some fine examples of his work in issues of ‘Dream’. Yet there was also John Light, Dreyfus and Dallas Goffin, who would go on to take fantastical art into new realms.

It was printed in a consistently neat pocketbook A5 format, initially of forty-eight pages but some later issues running to seventy-six or more pages. Initially published and edited by Trevor Jones (1944-1993) from his address in Godmanchester, Huntingdon, ‘Dream’ was in some ways a revival of an amateur ‘zine that he and George P Townsend had produced between November 1967 and December 1978, which had grown steadily more ambitious during that period. The revived version, though typed, was neatly reproduced (by Kilby Duplicating Service) and showed Jones’s conviction and commitment to producing as good a quality magazine as he could. This was not just in its appearance, which further improved with computer typesetting from issue no.17 (Autumn 1988) but in the content. It became a Weller Publication from issue no.10 (March 1987), the imprint of Townsend, who took over as editor from no.18 (Winter 1988) when he dropped his own magazine ‘New Moon Quarterly’ (which ran for five issues 1987-1988). ‘Dream’ was bimonthly until no.14 (November 1987) then quarterly, as ‘Dream Quarterly’, from Spring 1988, with the last two issues appearing irregularly. There were some good SF-poems, even if they were used as space-fillers, alongside reviews, and several nonfiction features including – from issue no.16 (Summer 1988), an astronomy column by Duncan Lunan.

Yet the ever-ambitious Trevor Jones, despite his increasingly poor health, decided in 1991 to upgrade ‘Dream’ into a fully professional magazine. Perhaps that was a step too far?, because as ‘New Moon’ – in an impressive glossy colour A4 format, it survived for no longer than two very powerful issues. It was able to draw upon the loyalties of Stephen Baxter and Peter F Hamilton who were by then already establishing themselves with novels, but even their strong cover-blurbed stories were unable to ensure the magazine’s long-term survival.

So what conclusions would the pensive robot sitting on the edge of the Moon’s rim finally decide upon? What cybernetic dreams were sparked within its impassive visage? That because of its regularity and reliability, and its strong stable of authors, ‘Dream’ developed a personality and a strong following unusual for British Small Press fiction magazines. That it served as a bridge uniting the old-guard ‘Ted’ Carnell SF with the post-New Wave. And that, although it may never have acquired the reputation or longevity of an ‘Interzone’, it should be celebrated as a key forum, and a market for British SF in the 1980s. That is no small achievement

DREAM: THE BEST

OF THE UNUSUAL

DREAM MAGAZINE No.1 (September 1985, 50p) editor Trevor Jones, with ‘Rave On’ essay by Sam Jeffers, ‘Keeper Of The Peace’ novelette by Harry Logan with Herbert Marchant, with short stories ‘Relic’ by George P Townsend and ‘Proof’ by S Stein

DREAM MAGAZINE No.2 (November 1985, 50p) with novelette ‘A Planet Named Victoria’ by Charles Luther, plus short stories ‘Danger Sign’ by Geoffrey Talbot, ‘Love Story’ by BK Lascher, and ‘In The Dream Cell’ by John Townsend (pseudo-religious tale by brother of George Townsend, he also has a story – ‘Thirty Degrees Of The Scorpion’ in ‘New Moon no.3’)

DREAM MAGAZINE No.3 (January 1986, 50p) with novelette ‘The Chessmen Of Rorn’ by Steve Worth, plus short stories ‘Draco’ by Gerry Connelly, ‘Calcified In Death Like Shining Stars’ by John Townsend (John emerges from the dark cellar into a series of increasingly strange alternate worlds, at first his altered office relationships with secretary Susan and the Colonel, then into nightmare landscapes, never explained or resolved), ‘Cute’ by Sydney J Bounds and poem ‘Saturday Afternoon Reflections’ by TE Wood

DREAM MAGAZINE No.4 (March 1986, 50p) with ‘Rave On’ essay by Sam Jeffers, short stories ‘High Noon’ by Martyn Taylor (voted best story of the issue), ‘With Malice Aforethought’ by Nik Morton, ‘The Miniatures’ by Sydney J Bounds, ‘Cloudgoddess’ by Bruce P Baker (Bruce Pelham O’Toole), and ‘Omega Legacy’ by Justin Meggitt, plus poem ‘Obituary’ by TE Wood

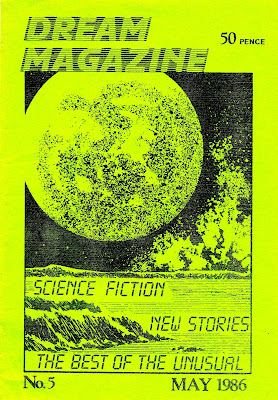

DREAM MAGAZINE No.5 (May1986, 50p) Steve Steed becomes assistant editor, with short stories ‘Cherchez Les Femmes’ by Charles Luther (Bruce P Baker ‘thought it saucy, suggestive and highly moral!’), ‘Last Act’ by Sydney J Bounds, ‘The Sound Of Gunfire’ by Sadie Shuttleworth, ‘Unprofessional’ by John Purdie, ‘The Cross’ by John Fraser, ‘Birdman’ by Alan Denman and poem ‘Autumn’ by TE Wood

DREAM MAGAZINE No.6 (July 1986, 50p) with novelette ‘Lost In REM’ by Christopher E Howard (‘the longest story we’ve yet published… no doubt you have heard the expression ‘the girl of my dreams’ on many occasions, well, the hero of Howard’s novelette becomes obsessed with the girl of his dreams – only question is, what can he do about it?’), ‘Matrix’ by Andrew Darlington, ‘Stress’ by PD Footfold, ‘Gone For A Spin’ by Sadie Shuttleworth. ‘The Melting Pot’ readers letters and ‘The Dream Quiz’

DREAM MAGAZINE No.7 (September 1986, 50p) with ‘The Angel Of Destruction’ by Peter T Garratt, ‘A World Of His Own’ by Gerry Connelly. ‘Earthquest (second Dr Sebastian Dimmock-Browne story, ‘just suppose that you were an alien with a nice sinecure in a galactic bureaucracy, you wouldn’t want anything to disturb your peaceful existence. But if your political opponents were closing in on you and threatening that nice cosy life, desperation might drive you to action. And – if the answer to your problems was on Earth then it might not be all that strange if you decided that’s where you had to go… of course, with the evil warlock Pendlebury K Wackett hovering in the background it might just turn out to be not so simple’)’ by Bruce P Baker, ‘Team Work’ by Rhoda Bevin Worrert

DREAM MAGAZINE No.8 (November 1986, 50p) with ‘A Turret In The Fury Eternal’ by Michael Cobley, ‘Oh, When I Joined The Eagles’ by Peter Reffold, ‘Killing Machine’ by Sydney J Bounds, ‘The Sins Of Billy Shane’ by Mark Iles, ‘Brave New Hamburger’ by Philip S Jennings, ‘Stranger In The Night’ by John Fraser

DREAM MAGAZINE No.9 (January 1987, 75p) with ‘The Arson Plague’ by Charles Luther, ‘Misplaced Person’ by Sadie Shuttleworth, ‘Fire Of The Dragon (second ‘Draco’ story)’ by Gerry Connelly, ‘Green Magic’ by Bruce P Baker

DREAM MAGAZINE No.10 (March1987, 75p) with novelette ‘Vassals Of Rorn’ by Steve Worth, short stories ‘Flesh And Metal’ by Ian (AG) Whates, ‘Suggestives’ by Arabella Wood, ‘Earth Fleet Rising’ by Mark Iles, ‘Tiger By The Tail’ by Sydney J Bounds, ‘Audience Participation’ by BK Lascher and poem ‘Coral’ by RB Leader

DREAM MAGAZINE No.11 (May 1987, 75p) with ‘Three Fingers In Utopia’ by Philip S Jennings (voted no.1 in issue, a poignant tale of a spaceman’s search for a perfect planet), ‘Rosemary’ by PD Footfold, ‘The Kondtratieff-Monroe Solution’ by Martyn Taylor, ‘Now You See It’ by Steve Sneyd, ‘The Forgotten Town’ by John Fraser, ‘My Home Towns’ by Gerry Connelly, and poem ‘The Yellow Sea’ by Kerk Tyme

DREAM MAGAZINE No.12 (July 1987, £1) with ‘The Rzawicki Incident’ by Gerry Connelly (ranked as the no.1 story of 1987, with anti-hero Johnny and his low-life reprobate cronies defeating the UFO-nauts at their own game), ‘A Time Of Giants’, by Arabella Wood, ‘A Dream Of Earth’ by Alan Denman, ‘Claudia The Goddess; by Peter Reffold, ‘Verdict Of History’ by Duncan Lunan

DREAM MAGAZINE No.13 (September 1987, £1) with John Townsend as assistant editor, with ‘Dark Pegasus’ by Bruce P Baker, ‘New Life’ by Tim Love, ‘Good Morning, Mr Bradley’ by Christopher Howard, ‘Second Century Koma’ by ER James (voted no.1 in issue), ‘Living In The Starships Shadow’ by Mark Iles and poem ‘From Hell To Heaven In Three Weeks by Michael J Hearn. ‘The Melting Pot’ readers letters and ‘Jeff’ comments by Sam Jeffers

DREAM MAGAZINE No.14 (November 1987, £1) with novelette ‘Company Man by John Purdie (a ‘strange, enigmatic story about a man displaced from his working environment, as a disc jockey on a satellite-based radio station, who comes face-to-face with some hard questions about the nature of reality’), short stories ‘The Bark Spaceship’ by Stephen (SM) Baxter, ‘Estelle’ by N McIntosh, ‘Butterfly’ by Dorothy Davies, ‘A Flash Of Lightning’ by Ian (IG) Whates, plus poem ‘Never Go Back’ by Steve Sneyd

|

| Alan Hunter artwork |

DREAM QUARTERLY no.15 (Spring 1988, £1.35) editor Trevor Jones, with ‘Voices Of Other Times’ by Peter T Garratt, ‘Green Troops’ by William King, ‘An Old, Old Story’ by Charles Luther, ‘Sea Changes’ by Graham Andrews, ‘The Judas Tree’ by Mark Iles, plus poem ‘Sunside’ by John Francis Haines, and interview ‘Writers Talking: Charles Luther’ conducted by Emmanuel Escanco

DREAM QUARTERLY no.16 (Summer 1988, £1.35) with novelette ‘The Huntress’ by Peter Reffold, short stories ‘Friable In Fragramento’ by John (S) Townsend, ‘Final Contact’ by Sydney J Bounds, ‘Perilous Greetings’ by Ian (IG) Whates, poems ‘The Dark Beyond The Firelight’ by Janet P Reedman and ‘Ghost Runner’ by Michael Newman, and interview ‘Writers Talking: John Townsend’ conducted by Emmanuel Escanco

DREAM QUARTERLY no.17 (Autumn 1988, £1.35) with editorial ‘Towards The Twenty-First Century’ by Trevor Jones, novelette ‘Time Of Uncertainty’ by Gerry Connelly, short stories ‘The Habitat’ by Stephen (SM) Baxter, ‘Red Garden’ by William King, ‘The Air Was Full Of Musics’ by John Light, ‘Dance, Zirillion Dance’ by Dorothy Davies, and ‘The Spacehopper’ by Arabella Wood, and interview ‘Writers Talking: Gerry Connelly’ conducted by Emmanuel Escanco

DREAM QUARTERLY no.18 (Winter 1988, £1.75) first issue edited by George P Townsend with editorial ‘Gazumpers Beware! Townsend’s Here!’, short stories ‘Jammers’ by Neil McIntosh, ‘The Fifth Freedom’ by Keith (N) Brooke, ‘Dreamgames’ by Phil Emery, ‘X+IY’ by Mike Maloney, ‘The Children’s Crusade’ by Sydney J Bounds, ‘Fireflies’ by Philip J Backers’ ‘Dr Wiacek’s Regeneration Machine’ by Nik Morton, ‘Future Tense’ by Gerald Blank, ‘Carefree’ by Linda Markley, plus poem ‘The Room’ by Michael Newman, and interview ‘Writers Talking: Peter Reffold’ conducted by Emmanuel Escanco

DREAM SCIENCE FICTION no.19 (Spring 1989) with editorial, ‘The Landlock’ novelette by Elizabeth and Erin Massey, ‘we ran no less than eleven stories, several of which were very short’ – ‘A Robot Handbag’ by David Gomm, ‘The Mage’s Meal’ by M John Deller, ‘The Fracturing Of A Steel Worker’s Faith’ by D Gill, ‘Tetragrammaton’ by Philip J Backers, ‘The Hand That Fed Him’ by DJ Lightfoot, ‘Uforia’ by Bruce P Baker, ‘A Tale Of Two Settees’ by Jenny Randles, ‘Welcome To The Dance’ by Dorothy Davies, ‘That Man Downstairs’ by Mark Iles, ‘If Music Be’ by BB Pelham, ‘Word Grid’ crossword and ‘Winter Stars’ poem by John Light, ‘About The Authors’ feature, ‘The Sky Above You’ essay by Duncan Lunan, ‘The Dark Side Of The Moon’ by Sam Jeffers, and interview ‘Writers Talking: Bruce P Baker’ conducted by Emmanuel Escanco

DREAM SCIENCE FICTION no.20 (Summer 1989) ‘Bumper Anniversary Issue’, with novelette ‘The Eighth Room’ by SM (Stephen) Baxter, short stories ‘The Roaring Sixties’ by Peter T Garratt, ‘You Are Old, Father William’ by Graham Andrews, ‘New Genes For Old’ by JP Gordon, ‘The Abreaction’ by ER James, ‘Angles’ by John Purdie, ‘Life Is A Four-Letter Word’ by Michael Cobley, plus ‘Word Grid’ crossword by John Light, ‘The Sky Above You’ astronomy by Duncan Lunan, ‘The Dark Side Of The Moon’ by Sam Jeffers (reviews of other magazines, ‘Interzone’ and ‘Crystal Ship’), ‘Pets Corner: Cyberpunk – The Comics Connection’ by Kevin Lyons, ‘The Melting Pot’ readers letters from Alan Hunter, Gerry Connelly, Peter Tennant and Keith Brooke, and interview ‘Writers Talking: Trevor Jones, George and John Townsend’ conducted by Emmanuel Escanco

DREAM SCIENCE FICTION no.21 (Autumn 1989) with ‘Two Great Novelettes’ ‘Do Det Ike’ by Gerry Connelly, and ‘The Suggestion Form’ by ER James (voted the issue’s no.1 story), short stories, ‘Sparkle’ by Charles Luther (art by David L Transue), ‘Reich’ by Marcin P Sexton, ‘The Memoirs Of Intern Zone’ by Peter T Garratt, plus ‘Word Grid’ crossword by John Light, ‘The Sky Above You’ astronomy by Duncan Lunan, ‘The Dark Side Of The Moon’ by Sam Jeffers (news and reviews of other magazines), ‘Pets Corner: Keyboard Reptiles’ by Philip J Backers, ‘Melting Pot’ letters. Ad for ‘The Edge’

DREAM SCIENCE FICTION no.22 (Winter 1989) with Trevor Jones editorial, novelette ‘Kismet’ by Keith (N) Brooke, short stories ‘Wheeler Dealer by Neil McIntosh, ‘The Sound Of The Sea’ by John Light, ‘The Birds’ by Tim Love, ‘Cities’ by Arabella Wood, ‘Time For Change’ by Mark Iles, poems ‘Just Visiting’ by John Francis Haines and ‘R And R In The LMC’ by Steve Sneyd, features ‘The Expanding Universe’ by Rod MacDonald, ‘The Dark Side Of The Moon’ by Sam Jeffers, ‘The Melting Pot’ letters, and interview ‘Writers Talking: DF Lewis’ conducted by Emmanuel Escanco

DREAM SCIENCE FICTION no.23 (Spring 1990) with George P Townsend editorial, short stories ‘Feminine Intuition’ by Lyle Hopwood, ‘The Dinosaur’ by Brian Rolls, ‘The Moral Consideration’ by GM Williams, ‘Murder By Magic’ by Sydney J Bounds, ‘Love Kills’ by Timothy Hurt, ‘The Watcher’ by AJ Kerr, poems ‘The Lilies Have Dried’ by David C Kopaska-Merkel, ‘Poems’ by Dave Ward (as David Greygoose), ‘Watcher At The Window’ by Janet P Reedman and ‘Permutations’ by Gaynel Thorold, features ‘Back In The Dreamtime’ by PC Feirtear, ‘The Neptune Encounter’ by Duncan Lunan, ‘Word Grid’ crossword by John Light, ‘The Dark Side Of The Moon’ by Sam Jeffers, and ‘The Melting Pot’ letters

DREAM SCIENCE FICTION no.24 (Summer 1990) with George P Townsend editorial, short stories ‘The Tyranny Of Heaven’ by Stephen (M) Baxter (voted no.1 story in issue), ‘The Grof’ by Philip Sidney Jennings, ‘The Last Space Opera’ by Peter T Garratt, ‘Zonk!’ by Gerry Connelly, ‘Blues In The Night’ by Bruce P Baker, with features ‘About The Authors’, ‘Earth Mission 2000’ by Duncan Lunan, Book Review, ‘Word Grid’ crossword by John Light, ‘The Dark Side Of The Moon’ by Sam Jeffers, and ‘The Melting Pot’ letters

DREAM SCIENCE FICTION no.25 (September 1990) with Trevor Jones editorial, novelette ‘Last Shreds Of X-Space’ by Mark D Haw, short stories ‘Bodywork’ by Peter (PF) Hamilton, ‘Bugs’ by Christopher (Chris) Amies (voted no.1 story in issue), ‘One Born Every Minute’ by Steven J Blyth, ‘San Diego Deadline’ by David E Slater, poems ‘The Gift Of Life’ by Ann Keith and ‘Vision’ by Ed Jewasinski, with features ‘Space And Art’ by Duncan Lunan, Book Review by Stephen J Wood, ‘Word Grid’ crossword by John Light, ‘The Dark Side Of The Moon’ by Sam Jeffers, and ‘The Melting Pot’ letters

DREAM SCIENCE FICTION no.26 (November 1990) with Trevor Jones editorial, short stories ‘Away An Old Dusty’ by Keith (N) Brooke, ‘The Singularity Man’ by Graham Andrews (reprint from ‘Focus no.2’ Spring 1980), ‘A Scent Of Heaven’ by David Gomm, ‘Dear Mum’ by DF Lewis, ‘Cut Price Bargain’ by Dorothy Davies, ‘Starlove’ by Christopher Howard (voted no.1 story in issue), poems ‘Cold Warrior Melting’ by DA Warne, ‘Song Of The Old Heroes’ by Wrathall Wildman, ‘The Messenger’ and ‘Hidden Secrets’ by Janet P Reedman, with features ‘The Year Of The Space Rescues’ by Duncan Lunan, Book Review, ‘The Dark Side Of The Moon’ by Sam Jeffers, and ‘The Melting Pot’ letters

DREAM SCIENCE FICTION no.27 (January 1991) with George P Townsend editorial, short stories ‘Major’s Children’ by Peter (PF) Hamilton (with Alan Hunter art) (voted no.1 story of issue), ‘Miss Blood’ by Jack Wainer, ‘Goddess Without Love’ by John Light (art by David L Transue), ‘Mr Pemberton’s Butler’ by Rik Gammack, ‘An Honourable Estate’ by Stephen J Wood, ‘Thoughts Of Rachel And An Overwhelming’ by AM Smith, ‘Word Grid’ crossword by John Light, Book reviews of Keith Brooke, Geoff Ryman, Ray Bradbury (by Peter Tennant) and Raymond E Feist (by DF Lewis), ‘The Dark Side Of The Moon’ by Sam Jeffers (reviews of ‘Exuberance’, ‘Peeping Tom’ – with advert, and others), ‘About The Authors’, ‘The Melting Pot’ letters from Mike Ashley, Stephen J Wood, Ernest (ER) James, John Francis Haines

DREAM SCIENCE FICTION no.28 (April 1991) with Trevor Jones Editorial (about launch of ‘New Moon’), short stories ‘Surviving The Night’ by ER James, ‘The Seer Of Souls’ by PF Hamilton (voted no.1 story in issue), ‘Dreamsense’ by Gerry Connelly (art by Tim Hurt), ‘Mother Love’ by John Gribbin, ‘Quintasextahuple Wow!’ by Charles Luther, ‘Jason’s Tale’ by Duncan Adams, ‘Waverider’ by Duncan Lunan (art by David L Transue), ‘Books Of Interest’ listing and reviews (Robert Rankin by Stephen J Wood, Diane Duane by Peter (PF) Hamilton, David Eddings by Bruce P Baker), and ‘Melting Pot’ letters from Adrian Hodges, Gerry Connelly

DREAM SCIENCE FICTION no.29 (July 1991) with Trevor Jones Editorial, novelette ‘The Retributor’ by Mark Haw (art by Alan Hunter), short stories ‘The Cyvernian Way’ by Andy Smith (art by Kerry Earl), ‘The Healer’ by Peter Tennant (one-and-a-half page short), ‘Saturday Night’ by John Duffield (voted no.1 story in issue), ‘Across Infinity’ by John Light (art by David Transue), ‘Chipwrecked’ by Andy Oldfield, plus John Light’s ‘Word Grid’ crossword, Book Reviews (Sheri S Tepper by Gerry Connelly, Barry Hughart by DF Lewis, Stephen King’s ‘It’ by Matthew Dickens, Bruce P Baker, Stephen J Wood, and PF Hamilton), science feature ‘The Weather On The Planets’ by Duncan Lunan, ‘The Dark Side Of The Moon’ (Sam Jeffers reviews ‘Fear’, ‘Interzone’, ‘REM’, ‘BBR’, ‘Exuberance, ‘Works, ‘Peeping Tom’ and others), the ‘Melting Pot’ letters from Peter Hamilton, Peter Tennant and Alan Hunter, with ads for launch of ‘New Moon’

A BOOK OF DREAMS (1990) edited by Trevor Jones and George Townsend, an anthology of the best SF from ‘Dream’ and ‘New Moon’ 1985-1987, with comments by Sam Jeffers, 80pp ISBN 1-873326-00-9, ‘The Angel Of Destruction’ by Peter T Garratt (from no.7, art by Alan Hunter), ‘Butterfly’ by Dorothy Davies (from no.14), ‘Tower Of The Kings’ by John Light (from ‘New Moon no.1’), ‘The Rzawicki Incident’ by Gerry Connelly (from no.12), ‘Three Fingers In Utopia’ by Philip Sidney Jennings (from no.11), ‘Second Century Koma’ by ER James (no.13), ‘Cloudgoddess’ by Bruce P Baker (from no.4), ‘Horse With A Roof’ by David Gomm (art by David Transue) (from ‘New Moon’), ‘Estelle’ by Neil McIntosh (from no.14), ‘Calcified In Death Like Shining Stars’ by John Townsend (from no.3)

NEW MOON no.1 (September 1991) ‘Britain’s Alternative SF Magazine’, edited by George P Townsend, ‘A Weller Publication’ with Trevor Jones Editorial, novelette ‘Sonnie’s Edge’ by Peter F Hamilton (part of the ‘Confederation Universe’ series, hard and brutal Gladiatorial contests in post-Global Warming flooded Peterborough, ‘Beastie-Baiting’ between avatar-controlled genetically-modified Turannor versus Khanivore), short stories ‘Before Sebastopol’ by Stephen (M) Baxter, ‘Desdemona’ by Matthew Dickens, ‘Green Soldier’ by John Duffield, ‘A Breaking Heart’ by Philip Sidney Jennings, plus John Light’s ‘Word Grid’ crossword, ‘Science Revisited’ feature by Duncan Lunan, and the ‘Melting Pot’ letters by Peter Tennant, Keith Brooke, John Francis Haines, Bruce P Baker

NEW MOON no.2 (January 1992, £2.50) with guest editorial by Trevor Jones, short stories ‘De-De And The Beanstalk’ by Peter F Hamilton (Alan Hunter art), ‘Two Over Seventy-Four’ by Keith Brooke, hitching a ride from Deimos to Callisto, Ray Stakopoulos becomes curious about the vain Tenant, only to get framed for his murder by his two clones (Kerry Earl art), ‘Crystals’ by Eric Brown (Tim Hurt art), ‘The Carnivorous Land’ by Andrew (Andy) Darlington (with Kevin Cullen art), ‘The Tree’ by ER James (Dallas Goffin art), plus ‘Dark Side Of The Moon’ pull-out section with ‘Master Of The Universe’ interview with Stephen Baxter conducted by Matthew Dickens, John Duffield magazine reviews (‘Interzone’, ‘Far Point’, ‘Peeping Tom’, ‘Scheherazade’ etc), Book reviews (Stephen Baxter’s ‘Raft’ by Matthew Dickens, Samuel R Delany’s ‘The Motion Of Light In Water’ by Peter Tennant, and others), John Gosling ‘Stripped: Comic Book Reviews’, ‘The Planet In Sagittarius’ science feature by Duncan Lunan, and ‘The Melting Pot’ readers letters from Peter Tennant, John Francis Haines