UNBOXED:

THE BOX INTERVIEW

You know this scene from television…

Concrete and glass hung mountain-high right out into space. Fashion-lepers pacing the crosswalks. Others slink under perimeter-wire and track across mud-slick flowerbeds into this anaemic white strip-light apron. Plate glass doors, corridors and staircases going on down to this planet’s core. I’m plea-bargaining with Official Heavies with the great barrier riff jack-hammering through the wall…

Then into the hygienic cold cavern of learning beyond.

Box on stage at the Sheffield University Students Union on accumulating momentum.

Unannounced, Charlie Collins, shock-bearded as a Russian anarchist, shrapnel bomb in alto, black face-fungus foaming luxuriously deep over black bib-‘n’-brace overalls and striped red-‘n’-black blazer, bayonets the mike with the bell of his sax and feeds a metallic patchwork wind-up into the air. A technique of tuning in, catching the rabble unprepared – off balance, that he used in his prior lifetime with Clock DVA. Then guitarist Paul Widger whips in, a red and orange Gibson, a chaotic autowreck of jaggedy-splinters fragmenting into abrupt chopped-up spat out staccato bursts of electricity wrapped around Terry Todd’s depth-charge Fender bass. A vague Jona Lewie lookalike, Todd spins and dips, to a sound to put your spine on the line, make your backbone flip.

Vocalist Peter Hope wears gold-rim reactalight spectacles and red braces, clings to the mike-stand in a double hand-lock like a man on fire. He ditches his red knitted skullcap and is stark bald beneath but for a single full-frontal quiff. He brays cut-ups of phrases in a voice of sand and glue with a kickback like he’s biting concrete, a voice that goes suddenly geometrical and continues out beyond point ‘x’. Language twists around his tongue like a live thing following a zigzag wandering course that recedes further and further from literal meaning until it’s hanging right over the edge – then jumps back into time. Copping its definitive position between the double-key control of horn and guitar, between outset and finale. Words like ‘atonal’, and ‘extreme’ suggest themselves, with comparisons yet more elusive, though Beefheart is possibly in there. Quotes come unbidden – like Arthur Miller’s ‘Art is made of conflict. It is not made of what we call pleasure.’ Yet in print it all melts down tarnished and devalued, before the sheer non-linear intensity of short antagonistic two-to-two-and-a-half-minute numbers ragged out with lacerations of adrenalin. A Satan’s laboratory in flame-out, no coasting in neutral, tripping out all tricked out in primal assaults so brief they hurt.

Remember ‘if it’s square, we ain’t there’?

Now forget it. With a chart EP – ‘No Time For Talk’ (Go! Discs VFM1, January 1983), due to be followed this month by their first album – ‘Secrets Out’ (Go! Discs VFM4, May 1983), squares they ain’t. Box is shaping up to be what 1983 sounds like.

‘Somebody wrote that Box ‘is for Rock fans only’ which I thought was terrible, a really diabolical comment’ growls Hope, voice like acid burns. (Slumped back heavy in the upholstery, slow, languorous, white-flesh of some recumbent Buddha. White shirt, tie held in place by gold clip.)

‘Yeah. It was a review we got. A really silly thing to write. We don’t mind good constructive criticism, but something as misleading as that, you just think ‘JESUS WEPT. HE’S WRONG! HE’S WRONG!’ Our music can appeal on a very basic level,’ Winged-Eel Widger rationalises. He’s the most verbal Box (short disciplined brushed-back blonde hair, denim jacket). ‘Some people like our music because it’s intricate and they find that interesting. Other people like our music just because they like the beat and the general noise of it. Which is fair enough.’

He shrugs, spears me with cautionary accusation. ‘This is the problem with interviews – it can present us as rather arty, when in fact the way we view it is…’ Suitably chastened I await the approved Party Line, the correct attitude I’m to assume. ‘The individual bits that we put into it aren’t that important, it’s the overall effect. You can listen to it on – not a superficial level, but you can just GET INTO IT if you like without ripping it open and saying ‘what’s he doing here?’.’

‘It’s just something that can appeal to the primitive’ offers Roger Quail, who eases gradually into the conversation as barriers come down. (Sheffield-steel bright, incisive, dark hair razored back at the temples. He produces the stable pulse-drumbeat to Box gems such as “Unstable” or “Limpopo”.)

All classic Rock has been intuitive, inspired accident, I agree. A distillation of the moment, rather than the technique behind it. but Rock is now near thirty years old, and it can’t escape self-awareness. It has technique as well… ‘We are not interested in technique’ rebukes Widger. ‘Talking about technique is a bit silly really. It’s irrelevant. Some things we play are very easy. Other things are difficult. It doesn’t MATTER. Personally I like to play things that are easy as possible. The simpler it is, the better. Simple ideas are usually the best. Our music is not really over-the-top or over-complicated. Some…’ he admits, ‘would disagree…’

--- 0 ---

Argument, disagreement, don’t come into it. Consciously or not there IS depth in Box – though it’s not necessary to overdose on it to appreciate the sound. The depth is both in the music, and the genealogy. At one point Paul Widger recalls the first time I wrote him up for ‘Hot Press’, ‘there was only a handful of local groups then, now there’s loads.’ And as that might indicate, it’s difficult to write about Sheffield without coming up against some cross-references. Stretching back as far as 1976, that initial handful of groups can be pared down to Cabaret Voltaire, and Future. After taping an innovative, bizarre and as-yet unissued album, Future bifurcated down the centre spawning Human League and Clock DVA (‘The Golden Hour Of The Future’, including “Blank Clocks”, “Dada Dada Duchamp Vortex”, “4JG” and others, eventually appeared on Black Melody Records, October 2002). Clock DVA consisting of ex-Futurians Adi Newton and Steven James ‘Judd’ Turner, plus the Box nucleus of Paul, Roger, and Charlie (Collins, already a veteran of ‘loads of local Soul, R&B and Jazz bands…’).

But ‘I think these connections you keep referring to are a bit misleading’ insists Paul. ‘That is going back a hell of a long time!’ But Clock DVA DID record with Cabaret Voltaire ‘on a four-track machine when Western Works wasn’t quite as sophisticated a studio as it is now,’ resulting in a slice of dense psychotic aural terrorism called “Brigade” – issued on ABC’s Neutron label. Following the critically successful album ‘Thirst’ (Fetish, January 1981), and ‘Judd’ Turner’s death from a heroin habit, the band imploded. Some previously unreleased material from this time survived, to be included on ‘The Last Testament’, a multi-artist compilation from Rod Pearle’s Fetish label (FR2011, live versions of “The Opening” and “Remain-Remain”, April 1983). But in the meantime, Adi retained the name for a new more Funk-orientated line-up, while simultaneously Box came into being, Terry Todd reinforcing the initial trio from a band called the Chants. You with me so far…?

‘We’re more interested in your writing about the Box as a new group, rather than relying on what we used to be in Clock DVA’ – from Roger Quail. ‘It’s history now. We’re pointing forwards.’ But (for the same of symmetry) I can’t resist a final poke. Talking to ABC recently there’d been gossip about the current DVA, inked to Polydor as their ‘token weirdo band’ – existing in a limbo position, with the label at a loss about how to market them. Widger won’t be drawn. ‘Possibly. That’s their concern, they’re really nothing to do with us now. They’re happy with Polydor, and we’re happy with Go! Discs, so everybody’s happy. That’s alright. Isn’t it?’

--- 0 ---

The first Box gig in its current, and probably permanent incarnation, was October 1982 at Sheffield’s ‘Leadmill’ co-op centre, followed by dates at the Brixton ‘Fridge’, and a scattering of gigs in Holland. Box was named by Charlie Collins, the original ‘white soul in a black suit’. But prior to finding Peter Hope they led an unstable germination period, including a brief vocalist hook-up with Ken Bingley, and another that brought the Cab’s Stephen Mallinder into Box. ‘We were never really a four-piece’ recalls Widger. ‘We were always looking for a singer. We wouldn’t have performed without a vocalist, but Mal (Mallinder) was only temporary. It was understood between us. He did – what was it? two gigs with us. I think he’d have liked to do more but it wasn’t possible with his other commitments’ (he sings “Something Beginning With ‘L’” on the ‘Secrets Out’ album).

How did that instability affect the evolution of the Box sound? Was there a basic set flexible enough to accommodate the changes? ‘Well, when Pete came in, some of the numbers were the same as what we’d done with Mal. He just put his own vocals over it. He wasn’t copying what Mal did at all – it was different. None of us – the original four, consider ourselves talented lyricists, so rather than make a bad job of what we could do, we thought it was better to wait until we found a lyricist who was happy to do it. It wasn’t so much a problem, we just had to find the right person. It took us a long time, but eventually… we found – Peter!’

Hope’s contribution is startlingly effective, selecting words with lethal economy. The stark stripped-down brutalism of the charting “No Time For Talk”, clear through to the hot-wired surrealism of “Water Grows Teeth” and “No Sly Moon” on ‘Secrets Out’ (as the first name-artists to be signed to ex-Stiff records conspirator Andy MacDonald’s Go! Discs). Quail explains that within Box there’s no writing axis, writing ‘is all done together.’ And – to Hope, the lyric method is ‘just getting the right feel. When you’ve rehearsed a song a lot of times you get to understand what’s going on – and I fit things in according to the music they make. Some songs don’t need much, vocal-wise. The voice is basically just another instrument.’

But then, the lyrics he’s written are mixed so far down it’s often difficult to decipher them, like you need subtitles in Ceefax. ‘That doesn’t frustrate me. Our songs aren’t – like, words and music. Separate. It’s everything together. It’s not very useful to split them apart. A lot of the words are used as a sound anyway, more than as a direct message. I structure lyrics to complement, or echo what else is going on. I’m not trying to say anything blatant with an obvious message. If we ever wrote anything with a deep message then we’d maybe do it in a different way. But at the moment, that’s the way I like to work.’ A wall-of-sound strategy with words infiltrated for their phonetic qualities? ‘Yeah. But it’s not like just saying ‘I’m writing a total load of crap just because the words sound good’. It DOES have meaning, but at the same time it’s equally important to make sure it sounds right. It’s expressing the situation that’s around you.’

‘The positive statement comes out of our music’ agrees Widger. ‘People say our music is very modern, very 1983, and in that sense it’s up to date. Being political is not just singing about Margaret Thatcher. You can express it musically through the tension and the general feel of it. The Jam’s approach was completely different, for example, it was a ‘writing on the wall’ thing. There’s nothing wrong with that, but our way is different.’

When John Peel played Box sessions he said they ‘worked from familiar reference points’. To me, that suggests Captain Beefheart. ‘That’s what he probably meant. Whether you agree with him, or we agree with him, is another question.’ So let’s ask that question. What reference points WOULD you admit to? DOES Beefheart figure in there? ‘Partly. We like Captain Beefheart. But we don’t make any deliberate attempts to copy…’

Quail rescues the drift. ‘It’s never been, like you see in a paper – MUSICIAN: and a list of influences. Because we happen to like certain people we never formed with the intention of trying to sound like them. You just bring along your own things, and they get – tangled around. And everything gets strained out into the sound we produce now.’

Which encapsulates it. Box ARE what 1983 sounds like. Not the artificial sound-footage you get when you tune into your Top Forty station. The airwaves still operate on the 99% is crap consensus principle. The lowest common aural denominator. Box don’t, and probably never will make good daytime programming material. In this sacrilegious era of mass plagiarism, they’re too extreme for that. Too hard and demanding.

Neither are they a fad tinsel band to get splashed across glossy fan-mag covers for the month’s duration of their fashionable currency value. I can’t ever see THEM making a complete three-minute promo-video episode of ‘The Professionals’ (replete with car chases and thefted ‘Blow Up’ motif) – and yet neglect to make a decent single to go with it. Box are concerned with sound. Sound so puritan-strict that on a scale of 0-to-10 Bo Derek would get around three. Bo Diddley might get more. A sound that is the near-perfect distillation of what 1983 is REALLY like. The tension screwed down on compression, the adrenalin overload, the subversive burn of frustration, the sadistic energy, the harsh complexity and the complex harshness all dismembered and reconstructed in white-heat anger. They define it non-verbally, yet so accurately, so intuitively, you only recognise it through the catalyst of their sound.

Also, despite their denials – I contend that Box retain the most elemental and vital fragments of Rock’s central nervous system. Although Rock is now too old and well-used for naivety, Box absorb the much-abused skeleton of its haunted past and furiously wig it out into the only zones possible thus far into the decade. They are the essence of 1983 in the way that ‘Blonde On Blonde’ is 1966, ‘Ziggy Stardust’ is 1972, or ‘Never Mind The Bollocks’ is 1977.

Yes, they are THAT good…

Album review of:

‘HOODOO TALK’

by PETER HOPE

& RICHARD H KIRK

(Native NTV28, 1987)

For those who lost hope when Capt Beefheart went absent-without-brain into abstracts, and for those who can’t decode the electro-pulse of passing Cabs, here’s two new Hoodoo Guru’s. Here’s a crash-course in creative dementia with rhythms chattering the language of chaos in meltdowns of awesome power – ‘hear the frame shake and groan, here the floor BENDS’ (“Numb Skulls”). Peter ‘The Voice’ Hope – formerly the bellow of Box, has a vocal styleé so over the top it’s out somewhere beyond Saturn, spanning octaves with an abruptness that hurts, low exhaust-trail rumblings accelerating through vast black wind-tunnel howls, with a surreal word-scramble targeted to irradiate the nerve-ends – ‘put your head in a noose, hang loose! …one vein to a drip, and one vein to a tap’.

And it’s all sound-tracked with a hyper-stimulus of seize-the-instant sequenced shocks programmed by Cabaret Voltaire’s Richard H Kirk who takes modern musics AND GUTS IT until each beat-per-minute strikes like surface-to-airwave missiles. A scattered debris of sonic architecture well-wired to weirdness, and even when Beefheartian analogies surface through the mix there’s some destabilising vox-tricks that even ‘Trout Mask Replica’ can’t replicate. He sings ‘sand drums on hot eyes’ (“Fifty Tears”), then he sings ‘it’s your face in my mirror, and it’s your comb in my hair’ (“Cop Out”), he sings of “Leather Hands” and “Surgeons”. Some’ll dismiss it all as ‘specialist’ music, but there’d be a lot more specialists attuned to its uniqueness if they’d give it a chance.

OPEN THE BOX,

AND TAKE THE MONEY!

Those who watch foreign movies on ‘Channel 4’ for the right reasons will recall the student party scene in the French ‘Lacemaker’ (1977, Dir: Claude Goretta). An attempted intellectual lectures at inordinate length expounding the apparently obvious idea that we live our lives in a series of ‘boxes’ – schoolroom, flat, car, office, coffin. His rapt and enraptured audience, all long black hair and existential dark shades, then debate the political and sociological significance of this boringly mundane concept of Cubism. Perhaps something got lost in the subtitles…?

Us in the know have been aware for some time that Box is important.

‘It was just a name that was short, punchy, easy to remember,’ explains guitarist and main policy spokesman Paul Widger. ‘Because at the time we chose it there was a trend to longer, more involved names. We wanted something short and snappy. I don’t think we could’ve done much better than Box. It’s got a different interpretation for everybody.’

‘The overtones start to come in’ agrees Roger Quail, the dark, deceptively slight drummer. ‘It’s television. It’s inner space. It’s things like that. But that was never the intention when we christened us-selves. It was just something very very simple. There aren’t many three-letter words that end in ‘X’…’

I offer ‘Hex’? But Poison Girls got a pre-emptive strike with that one.

Box is the Sheffield five-piece who first broached the Indie lists with a garishly Peter Care red ‘n’ silver-sleeved five-track EP. Its titles hinting at its ingredients – “Hazard”, “Unstable”, “Burn Down That Village”, a dense morass of rabid rhythms collectively called ‘No Time For Talk’ (Go! Discs VFM1, January 1983). A furiously wigged-out jarringly stop-start sound shot full of dark hordes of jazz. A fast-forward sound that kicks the door down, lambasts eardrums and rearranges brain-cells. A sound so intense it derailed some reviewers, but the to-critical-mass-and-beyond approach now flared wide-screen on their first album should make converts. Box defy category, compartment, pigeon-hole, or geometrical preconceptions.

Their sound symmetrically counter-balances the taped disco soundtrack casting its stupid wrap-around glow over the licensed lounge where I meet the group. ‘No Time For Talk’ perhaps, but we cram in plenty of backchat prior to their onstage set.

Vocalist Peter Hope, who’s sat wall-eyed through most of the conversation, leans forward, his single gold cross earring exploding the light beneath the turn-up of his tight red knitted skullcap. He offers some sign-posts. ‘There’s been reference to us, trying to lump us in with people like Sex Gang Children and Southern Death Cult – which is pretty well off the mark. Seems like a need to categorise bands into their own little box.’ No added overtones intended. The ferocity and attack is ‘just the way we play, and how we’ve always played. It’s natural, not something we work on.’

But other critic’s analogies with the Rip Rig & Panic New Jazz thing are just as emphatically booted. ‘In various songs there’s room for improvisation, or different expression. But it’s not like wild free-form or anything. Most of it’s written. It’s pretty tight.’

‘A lot of crap goes under the banner of improvisation these days. Idiots with trumpets. We find it more interesting playing to a strict discipline,’ expands Widger. And for good measure ‘we don’t like to consider ourselves part of a ‘scene’ in Sheffield either. It’s not that we’re snobby, but we like to remain totally independent from that. I don’t think we’re like any band in this area at the moment. There isn’t one that’s vaguely similar to us.’ Geographically that’s true, but last time I saw Quail, Widger, and bearded saxist Charlie Collins, they were components in the magnificent and hugely underrated Clock DVA. Some of the fanatical commitment of that group seems to spill over into their second coming with Box. ‘Partly, yes, there are slight similarities’ agrees Widger grudgingly. ‘Some of the basic ideals are the same, we haven’t compromised or anything. But that’s history now. We’re pointing forward. We think of Box as a completely new thing.’

There is, however, one further link between the two lifetimes – Psychic TV producer Ken Thomas. He was responsible for DVA’s first album, the neglected classic ‘Thirst’ (Fetish, January 1981). ‘Yes, that’s how we got to know him. We’ve no longer got any links at all with Fetish 9the label run by Rod Pearle, which issued early DVA and Throbbing Gristle tracks), but when we wanted to record as Box we thought we’d like to use Ken again. One of the good things about using him this time around is that studio time is extremely tight. We didn’t have long to work on it, and it helps if you’ve got a working relationship already established. It means you can go straight in and get on with it rather than getting to know each other first.’

‘As a result’ says Quail, ‘our album was recorded at Jacob’s Studios in Farnham over just nine days (from 15 October 1982). And it’s called ‘Secrets Out’ (Go! Discs VFM4, May 1983). The track extracted for the ‘NME’ compilation ‘Racket Packet’ – “Out”, is one of the songs we recorded then, put out as a bit of a taster, y’know…’

‘It’s different for us as well if you think about it – having short songs, if you’re gonna do an LP, you’ve got to have a lot more of them. You can’t just stick down four basic riffs and develop an album out of it. It takes a long time because we take a lot of care over what we write, and we reject a hell of a lot of stuff. So coming up with twelve songs is a tall order.’

‘…We actually recorded thirteen tracks with the intention that – just prior to the LP coming out, one of the tracks (“Old Style Drop Down”), would be remixed and released as a single with a different ‘B’-side which isn’t on the album. I think we’re all happy with the sessions. It was pretty much different to the ‘No Time For Talk’ five-track we did. The sound’s different.’

Some of that newly-vinylised material was unleashed live at the ‘ICA Press Gang Week’, when Box mugged the audience with a shock set sandwiched between a cliquishly diverse circus of performers – and the upwardly mobile JoBoxers. Peter – as a Londoner, the only non-Sheffield accent in Box, found that audience ‘stand-offish, a bit unsure. It was a very strange night.’

‘We were invited to do it, to kick the evening off to a good start’ relates Quail. ‘To make an impact, because the rest of the evening was taken up with Poets, Skiffle groups, that sort of thing. We went on at some ridiculous time, I think it was about eight-o’-clock when the people had just come in off the street and hadn’t warmed to it all…’

‘…And we just played a very very intense set,’ from Peter.

‘We played it very straight, in from the top. No mercy at all,’ from Roger.

‘It was a bit much for some people, they were expecting a hip-type Funk outfit or something. And they got us instead! That’s quite funny. But I thought it was great myself.’

Is that high-energy, short-number, pressure-cooking technique a deliberate strategy? ‘No. they just turn out like that. We don’t flog things to death. We cram a lot of ideas into a short song, so there’s no reason to drag it out to ten minutes.’

On the ‘back to the Ramones’ principle? A disintegration into laughter. But isn’t it more satisfying to allow a song to evolve, to explore and develop it? ‘That’s a very traditional point of view’ Widger rebukes. ‘There’s no ‘getting into’ a song – you’re into it from the word GO! We know what we’re doing. It’s not like two-minute improvised pieces most of the time. It’s written pieces.’

‘There’s a lot in every song’ agrees Hope in a slow drawl that’s rusted around the edges. But the method of song construction ‘varies’.’

‘Usually we start either from a drumbeat or a guitar part – usually, but not always.’ Paul Widger. ‘Sometimes it’ll be (Terry Todd’s) bass or Charlie’s saxophone. Then everyone will think about it and sit around it, see how it grows. Everyone is very actively involved in the writing process. That’s the only way it works for us. It wouldn’t work if one person was writing apart.’

‘We’re still not working at us full capacity’ opines Quail. ‘We’re only warming up in a way…’

Widger closes emphatically. ‘There’s loads of things we can do. And we will do…’

Boxes – whether social, political, or journalistic, only dominate lives if people allow them to. Box bust out beyond all such restraint. Box defy the process, they draw up their own rules, and MAKE them work. That’s what makes them so unpredictably exciting. It may be only halfway into the year, but already their kind of cubism is the shape for 1983 hereabouts.

(Published - in Italian, in ‘Rockerilla’)

RE-BOXED

Box were formed in 1981 in Sheffield out of the ashes of Clock DVA. DVA members Paul Widger (guitar, vibraphone), Roger Quail (drums) and Charlie Collins (saxophone, flute, piccolo flute) recruited new member Terry Todd (bass) and tried several vocalists including Stephen Mallinder of Cabaret Voltaire before deciding on Peter Hope. Widger had also recorded as part of They Must Be Russians as ‘Paul Russian’, on the January 1979 EP ‘Nellie The Elephant’ (Not On Label RVS001) recorded at Western Works

January 1983 – THE BOX: NO TIME FOR TALK (Go! Discs VFM1, 12” vinyl EP) with “No Time For Talk”, “Burn Down That Village”, “Unstable”, “Hazard”, “Limpopo” cover art by Peter Care, Producer Ken Thomas. Reaches no.12 in ‘NME’ Indie chart after entry 29 January, and staying four weeks.

May 1983 – OLD STYLE DROP DOWN (Go! Discs VFM2) 7” vinyl “Old Style Drop Down (Remix)” c/w “Momentum”, with 12” vinyl (VFM3) “Old Style Drop Down (Extended Remix)” c/w “Old Style Drop Down” + “Momentum”, cover-art Peter Care, producer Ken Thomas. Enters ‘NME’ Indie chart 28 May, reaches no.22 the following week

17 June 1983 – SECRETS OUT (Go! Discs VFM4) with “Water Grows Teeth”, “Skin, Sweat And Rain”, “Something Beginning With ‘L’” (vocals by Stephen Mallinder), “Strike”, “The Hub”, “Hang Your Hat On That!”, “I Give Protection”, “No Sly Moon”, “Slip And Slant”, “Old Style Drop Down”, “Swing”, “Out”, cover-art by Peter Care, recorded at Jacobs Studios 19-23 January with producer Ken Thomas. ‘Melody Maker’ says ‘this is a music free of sentiment, a music of action shot through with nervous energy, channeled belligerence and extravagant ambition’. Box play ‘Brixton Ace’ supporting X-Mal Deutschland (23 June) and the Fall (15 July). Then Newcastle ‘Dingwalls’ (20), Leeds ‘Warehouse’ (21), and Hull ‘Dingwalls’ (22), followed by European dates through August

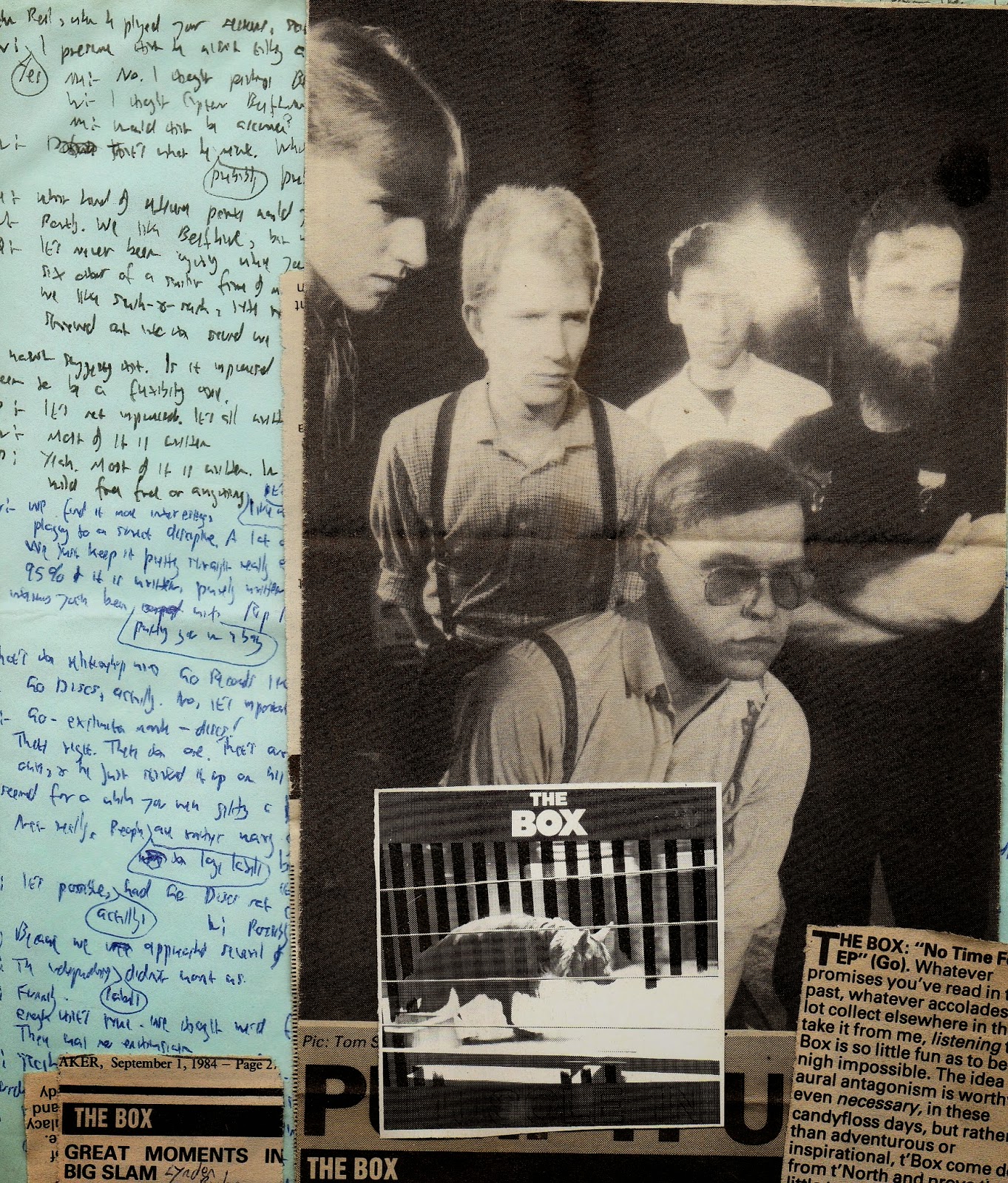

June 1984 – GREAT MOMENTS IN BIG SLAM (Go! Discs VFM5, also cassette ZVFM5) with “Walls Come Down”, “The Flatstone”, “Big Slam”, “Stop”, “Low Line”, “Breaking Strain”, “Small Blue Car”, “Still In The Woodwork”. Scratchy cover cave-drawing by Pete Care. Produced by Dick O’Dell. ‘Melody Maker’ says ‘Stop Press: BEST BOX YET. A fast whirlpool of spittle, grit and polished madness’

1984 – MUSCLE MIX (Doublevision DVR P1, 12” vinyl) after two albums on Go Discs Box link up with Cabaret Voltaire’s Doublevision label where they release some EPs in a more electronic style. “Crow Bar (Muscle Mix)” c/w “Low Commotion (Muscle Mix)”, remix by Richard H Kirk

November 1984 – MUSCLE IN (Doublevision DVR10, 12” vinyl EP) With “Low Commotion”, “Curfew”, “Crow Bar”, “Spade Work”, recorded at Western Works with producers Mark Estdale and Richard H Kirk. “Crow Bar” later issued as limited edition 12” single

1985 – MUSCLE OUT: THE BOX LIVE (Doublevision DVR P3) with “Bottle Drips Dry”, “Big Slam”, “Jaw Clamp Sunshine”, “Pawn Walk”, “Rose High”, “The Hub”, “Breaking Strain”, “Deeper Blue”, “Stop”, “Momentum”, “Old Style Drop Down”, “No Time For Talk”

‘NME’ (26 January) announce final Box gig at ‘The Leadmill’ on the 29th. Following the break-up Charlie Collins joins Bass Tone Trap, collaborates with Sonny Simmons, Ted Daniel, Beatrix Ward-Fernandez (‘View From The East’, 2009), Eun-Jung Kim, The Bone Orchestra and Hunter Gracchus. He appeared on ‘Top Of The Pops’ with Moloko, and works with Derek Bailey’s experimental Jazz Company. Collins and Peter Hope are reunited with Paul Widger on Bone Orchard album ‘When Will The Blues Leave?’ (1987, BACON 404) and the Flex 13 CD ‘Candy’ (1999, Liquid LIQ022CDL). Terry Todd plays with the reunited Comsat Angels in 2009. Roger Quail drums with Cabaret Voltaire (including 1984 LP ‘Micro-Phonies’)

1985 – LEATHER HANDS by Richard H Kirk and Peter Hope (Doublevision DVR15, 12” vinyl EP) with “Leather Hands (Master Mix)”, “Leather Hands (Radio Mix)”, “Leather Hands (Crash Mix)” recorded at Western Works drum programming and producer Richard H Kirk. The duo also collaborated on October 1987 album ‘Hoodoo Talk’ (Native Records NTVCD28) with “Intro”, “Numb Skull”, “N.O.”, “Cop Out”, “Surgeons”, “Fifty Tears”, “Leather Hands”, “Fifty Tears (Reprise)”

August 2014 – THE BOX @ DOUBLEVISION CD album in a limited edition of 300 copies. | gg189 Klanggalerie now proudly presents the collected Doublevision works by this phenomenal group, including several remixes by Richard H. Kirk - two of which remained unpublished until this CD collection. In the unlikely case of you not knowing what The Box sound like: imagine a Sheffield funk band with elements of jazz & sax, a Cab Volt meets Miles Davis kind of music with a vocalist that could also be Captain Beefheart.

1 comment:

Gain your access to 16,000 woodworking plans.

Teds Woodworking has over 16,000 woodworking plans with STEP BY STEP instructions, pics and diagrams to make each project simple and easy!

Post a Comment