FROM HERE…

TO ETERNITY:

STEPHEN BAXTER’S

‘THE TIME SHIPS’

Book Review of:

‘THE TIME SHIPS’

by STEPHEN BAXTER

(HarperCollins 1995, Voyager Paperback 1995

ISBN 0-00-648012-8)

THE GEOMETRY OF FOUR DIMENSIONS

‘I am by nature a speculative man…’ Tomorrow will be different from today, in subtle minor details. We know and understand this. Next year will be different from this year in some unexpected and surprising ways, although most of it will remain pretty-much the same. Next century though, begins to set up questions. In all likelihood we will no longer be around, but family elements of our DNA probably will. It’s only human to wonder, to speculate what the world will be like a hundred years hence. And if a hundred, why not a thousand years? A million?

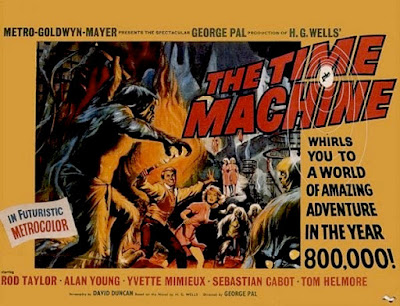

HG Wells’ seminal narrative ends with the Time Traveller (‘for so it will be convenient to speak of him’) vanishing into futurity in hopes of returning to 80,701 to rejoin the ‘little doll of a creature’ who is the lovely Weena, by the White Sphinx on future Richmond Hill. Stephen Baxter’s sequel, authorised by the Wells Estate, picks up the tale at exactly that point, and immediately plunges its nameless protagonist into new horrors. The Earth’s axial tilt is corrected – eliminating seasons, then the day-night rotation reduces to a halt until Earth is gravitationally-locked with one hemisphere forever facing the sun… then the sun itself explodes. All within the first fifty pages.

Wells original “The Time Machine” is little more than a novelette. Baxter expands it to 630 mind-stretching pages. The same Chronic Argonaut who first jaunts through the fourth dimension, now finds himself lost in a quantum universe of parallel ‘Long Earths’ in which tomorrows are fluid and uncertain, nothing is fixed. Each trip through time simultaneously splits off new alternate time-streams, while apparently eliminating previous possibilities. Weena’s future – it seems, is deleted, inaccessibly lost in the relativistic flux. Which means that the temporal device has become ‘more powerful than a mere time-travelling machine: it was a History Machine’ – and, echoing Robert Oppenheimer’s comment after witnessing the first nuclear explosion, the Time Traveller himself has become not only ‘a destroyer of worlds’ but a ‘murderer of the future.’

He was rapidly followed by Ray Cummings’ ‘The Man Who Mastered Time’ (1924), and John Taine’s ‘The Time Stream’ (1931), until Jack Williamson’s ‘The Legion Of Time’ (1938) expands the theme to an even greater scale. Ray Bradbury’s classic short story “A Sound Of Thunder” (1952) ties logical knots in the cause-and-effect of time-tampering until Robert Silverberg’s ‘Up The Line’ (1969) playfully pitches contradictions against each other. David Lake even attempted a direct sequel of sorts with his novel ‘The Man Who Loved Morlocks’ (1981) and short story “The Truth About Weena” (1999). ‘The Terminator’ and ‘Back To The Future’ movie franchises take time-travel conundrums into mainstream cinema. Even Dr Who must be considered a distant relation of Wells’ first Time Traveller.

REMARKABLE BEHAVIOUR OF AN EMINENT SCIENTIST

After all of that, how can there feasibly be a full sequel? Is it even possible that that first mental napalm assault can ever be recaptured? That Stephen Baxter succeeds magnificently on just about every level marks him out as the major writer of his generation. He adds detail that Wells does not. He uses the mysterious Plattnerite which does for time what Cavorite does for gravity. In doing so, he sequesters Sussexville Proprietary School master Gottfried Plattner into the tale – initially a man whose internal organs have somehow become transposed, in “The Plattner Story” first published in ‘New Review’ (April 1896). In Plattner’s own account, scrutinised by the ‘Society For The Investigation Of Abnormal Phenomena’, he reveals how he was originally given an eight-ounce graduated medicine bottle of a glowing green powder found in a disused limekiln by a pupil named Whibble. It explodes, and although the tale opens on a none-too-serious tone, Plattner is cast into an Other-World ‘state of existence altogether out of space,’ and his nine-day sojourn in a ‘green-lit half-world outside the world’, a ghost-realm beyond death, is genuinely unsettling. As are the ‘Watchers of the Living’ he encounters there. Although unconnected by Wells with “The Time Machine”, Baxter creates that text-link by seamlessly integrating its elements.

Back in 1873 the Time Traveller meets his own younger self – who he calls by his resented first name Moses. Meeting yourself is one of the temporal paradoxes that have troubled multiple fantasists across the years intervening betwixt Wells and Baxter. Untroubled by such riddles, he attempts to dissuade this younger self from inventing the Time Machine in the first place. Obviously, should this warning have succeeded, the entire narrative up to this point would cease to exist! Yet instead he’s pitched into a further ‘blizzard of conflicting histories,’ as if the Time Machine ‘once invented, its ramifications were spreading into past and future,’ so that even his own past ‘was no longer a place of reliability and stability.’ Otherwise, would he not already posses memories of these events? Indeed, with infinite probability, it’s even likely that in some alternate time-lines ‘Moses’ heeds persuasion, and does not build the Time Machine, while in others he does, skating around on the river of time ‘like a water-boatman,’ as the wise Morlock introduces both selves to the ‘Many Worlds Interpretation Of Quantum Mechanics’.

The duo of Morlock and Time Traveller are expanded by earlier-self Moses into a trio of temporal-tourists when they encounter Filby – Wells ‘argumentative person with red hair’ who was the only named guest in the smoking room of the original Richmond dinner-party (along with the Medical Man, the Very Young Man, the Editor of a well-known Daily Newspaper, the Silent Shy Man with a Beard, and others). Filby is now aboard a Kitchener-class Juggernaut from the 1914-1938 Siege Of Europe. A part-reference to the European War that Wells predicts in his Alexander Korda-produced movie ‘Things To Come’ (1936), as well as anticipating the steam-punk militaristic invention of ‘The Massacre Of Mankind’ (2017), Baxter’s authorised sequel to the 1897 novel ‘War Of The Worlds’. In this alternate history, Central London is domed in defensive concrete as protection from aerial torpedoes and gassing. Although how the Juggernaut avoids relativistic Time Traps to navigates its accurate way home is not explained.

Another real-life character from twentieth-century history, Austrian-born logician, mathematician and philosopher Kurt Gödel speculates about finding a metaphysical ‘Ultimate Meaning’ through the catalyst of alternate time-streams and a ‘Final World’ in which all meaning is resolved. Lord Beaverbrook is there too, in league with the Babble Machine kinematographic propaganda, and George Orwell – ‘a bit of a writer’, plus an Elliot poem – and even a cartoon Desperate Dan. Then there’s HG Wells himself, formerly the ‘writer’ at the Richmond party, but now an old man, ‘his fiction isn’t what it was, in my view – too much lecturing and not enough action.’ Within the planned post-war New World Order, both collectivist and puritanical, there are elements of the toxic eugenic control – ‘directing humanity’s racial heredity,’ a proto-fascist political ideology that Wells himself was briefly seduced by.

Like Wells, Baxter sees ‘beyond the surface of it all.’ ‘There is no rest. No limit. No end to the Beyond – no Boundaries which Life, and Mind, cannot challenge, and breach.’ There’s a soaring optimism about Baxter’s Optimal History that has something of Olaf Stapledon’s endless vision too.

Immensely readable, endlessly inventive, and a hugely enjoyable adventure, could Wells have written a sequel such as this? Obviously not. Baxter draws on quantum and Big Bang physics unsuspected in Wells’ day. The space-time continuum has complexified beyond the simplicity of Wells early model. But if Wells were writing today – yes, he’d have revelled in this new Information Sea.

Yet I still don’t know how to pronounce Nebogipfel.

No comments:

Post a Comment