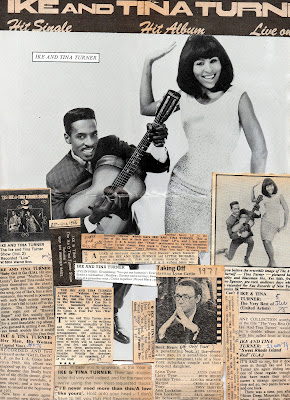

HELEN SHAPIRO:

TOPS WITH HELEN!

‘Gonna be my own adviser,

‘cos my mind’s my own’

not only a Helen Shapiro hit single in 1961

– but a feminist teenage manifesto too

‘Gonna have my fun’ asserts Helen Shapiro, ‘so if I feel like running wild, please don’t treat me like a child.’ Hardly startling to hear that now. In 1961, “Don’t Treat Me Like A Child” was a revelation. The earth moved. New forbidden freedoms beckon. This is the advance tremor of the whole Sixties Youthquake to come.

On black-and-white TV, Helen wears the regulation flared skirt, her dark hair piled into the regulation bouffant beehive. But if she occasionally appears stiff and a little formal onscreen, when she sings ‘it’s often said that youngsters should be seen and not be heard, but I want you to realize, that’s quite absurd, don’t wanna be so meek and mild’, her poise only serves to underline her conviction. Articulate and well-reasoned, her argument for self-determination precedes Cliff Richard’s more generationally anthemic declaration “The Young Ones” by six months, yet there’s also something of the Who’s “My Generation” in there too, and every subsequent appeal to declarations of youth independence, clear down to the Spice Girls ‘Girl Power’ sloganeering. But did anyone phrase it better than ‘gonna be my own adviser, ‘cause my mind’s my own, then I will be much the wiser, my own point of view has got to be known’? I doubt it.

I was thirteen. I was at school too. I watched her performing her hit on ‘Thank Your Lucky Stars’. Never alluringly sexy in the way that Ronnie Spector, PP Arnold or Marianne Faithful were, Helen was more the sensible level-headed girl you could take home to meet your Mother. But there’s subtle gender-subversion in each groove of that 45prm single.

Helen Kate Shapiro was born 28 September 1946, the granddaughter of Russian-Jewish immigrants, in Bethnal Green, part of London’s East End. Brother Ronnie fed in a strong Jazz bias, cousin Susan (Singer) also sang, and Marc Feld – the later Marc Bolan, was a school-friend who ‘lived down the road’ and fooled around on guitar. She did talent shows, and by age thirteen Helen was a pupil at Clapton Girls School, while her father raised the 25-shilling fee necessary for her to moonlight as a protégé at the Baker Street ‘School Of Modern Pop Singing’, the Fame Academy of its day. Alma Cogan was a previous beneficiary of its renowned voice coach Maurice Burman, who also functioned as Helen’s manager, until his death, when his wife Jean assumed the role.

It was here that a talent-scouting John Schroeder overheard her timbre-rich singing, mid-lesson during a visit. He was so impressed he arranged some trial recordings for her. EMI’s label manager Norrie Paramor had guided its Columbia subsidiary to dominance by first taking a chance on recording Cliff Richard & The Drifters. Schroeder was assistant to Paramor – who at first refused to believe that the rich bluesy voice he heard doing “Birth Of The Blues” on the demo belonged to a fourteen-year-old. Again, Paramor took a chance, and signed her up to Columbia’s A&R department.

“Please Don’t Treat Me Like A Child” was the direct result. Calculatedly, and perhaps even cynically written by two male twenty-six year-olds – Schroeder himself with lyricist Mike Hawker, it was in every sense a Feminist generational anthem. Although artfully slanted to Helen’s exact requirements – ‘just because I’m in my teens, and I still go to school,’ if they were the ventriloquists, Helen interprets the song with precocious self-confidence, clarity of phrasing, and a degree of mature soulfulness that leaves no doubt of her authenticity. Initially a ‘sleeper’, it only took an exposure slot on ABC-TV’s ‘Thank Your Lucky Stars’ to focus attention. It enters the chart at no.38, 23 March 1961, climbed to no.28 the following week… and by 11 May it was peaking at no.3. Overnight she was leading a double-life, a national celebrity, and the schoolgirl with the grown-up voice, a star on TV, while still sitting behind a school-desk.

Pop loves duality – for every Elvis a Cliff, for every Beatles a Stones, for every Oasis a Blur, and there was an attempt to build Susan Maughan into a rival-Helen Shapiro. Susan was bright and bubbly, although her biggest, and only significant hit – “Bobby’s Girl”, a no.3 in October 1962, was not only a straight cover of Marcie Blane’s American hit, but was thematically woeful. Where Helen snaps down ‘don’t think that I dream childish dreams, I’m nobody’s fool’ – for Susan ‘when people ask of me, what would you like to be, now that you’re not a kid anymore-ore’ the most important thing to me-ee, she answers right away, is to be the simpering thankful grateful arm-candy for hunky Bobby. Hardly a suitably aspirational ambition for a role model!

Susan continued as a presence, and features opposite Joe Brown in the movie

‘What A Crazy World’ (1963), she even scored a minor chart entry with a pointed “Hand A Handkerchief To Helen” – no.41 in February 1963, but it was Helen Shapiro who easily carried off the

‘New Musical Express’ Poll Award as ‘Top UK Female Singer’ both in 1961 and 1962. Cousin Susan Singer also generates press with her own 1962 single “Gee, It’s Great To Be Young” c/w “Hello First Love” (Oriole), but Helen remains unique.

Before Helen, there had been Shirley Bassey and Petula Clark who – as Helen later told

‘Mojo’ magazine, ‘were great, but they were more showbiz.’ Helen was different. She was one of us. With her presence firmly established, her next two singles each sell progressively better than the one before. “You Don’t Know”, a wistfully dark heartbreak ballad of unrequited love, again written by Schroeder and Hawker, and produced by Norrie Paramour at the Abbey Road Studios with a nine-piece Martin Slavin band-arrangement, was no.1 for three weeks from 10 August 1961. By topping the charts with a quarter-million sales of her second single – at just fourteen years and 316 days old, she not only became the youngest girl, but the youngest British artist to score a no.1. But not the youngest person. American Frankie Lymon had been a year younger when he did that in 1956 with “Why Do Fools Fall In Love”.

While the decade around her was already shifting into new configurations, three days after “You Don’t Know” peaked – in a move apparently unconnected to the record’s success, the East Germans began building the Berlin Wall.

The same writer-producer team was responsible for the up-beat third single – “Walkin’ Back To Happiness”, with Helen’s throaty black-velvet tones winning out over squeakily-chirping female back-up singers. ‘I didn’t like it then’ she told journalist Norman Jopling (

‘Record Mirror’ 24 December 1966), ‘and I still don’t’, but it was a second no.1, again holding the top slot for three weeks, from 19 October 1961, with UK sales of half-a-million – the same week that birth control pills became available through the NHS. Soon she was back on ‘Thank Your Lucky Stars’ (30 December) too, alongside ‘America’s King Of Twist’ Chubby Checker, Billy Fury, with Cliff Richard & the Shadows.

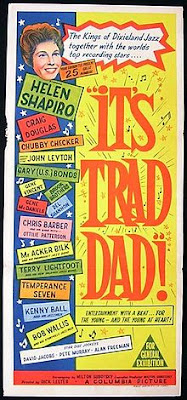

Two more hits followed in 1962, taking her total UK sales to well over a million. By her fifteenth birthday she’d made over a dozen radio and TV appearances, topped the bill on ‘Sunday Night At The London Palladium’, and featured in a Rank Films ‘Look At Life’ docu-film featurette, as well as starring in the film

‘It’s Trad Dad’ (March 1962). She left school at the end of the Christmas term 1961 to commence film-work. The first movie to be directed by a young Richard Lester, for horror-studio Amicus Productions, it remains a curious period piece. It has a flimsy plot involving disapproving adults attempting to ban the local coffee-bar jukebox, and devious council officials conniving to frustrate a support-concert for the ‘kids’, all of which is simply an excuse to string together disparate hits by John Leyton and jazzers Acker Bilk, Kenny Ball and Chris Barber with token American artists designed to add US-appeal – Del Shannon, Gene Vincent and Gary US Bonds joining Twist-King Chubby Checker for a series of cameos (the film was retitled

‘Ring-A-Ding Rhythm’ for the USA). The nominal stars who agitate protests with radio DJ David Jacobs, ‘Helen and Craig’, are the thinly-disguised Shapiro and clean-cut Craig Douglas who had a string of inoffensive cover versions of American hits. Yet the film was successful, making impressive profits for Max Rosenberg & Milton Subotsky, its notorious exploitational producers.

The film’s premiere coincided with another significant first, the release of Helen’s debut album,

‘Tops With Me’, which seems to consist of a poorly thought-out hodge-podge of whatever songs happen to be lying around at the time, Connie Francis’ “Lipstick On Your Collar”, Brenda Lee’s “Sweet Nothin’s” and Neil Sedaka’s “Little Devil”. Yet it, too, sells impressively, reaches no.2, spawns two spin-off EPs, and remained on the album chart for half a year. Helen would go one to record more – and better, albums. But none would sell so well.

Subsequent singles, “Tell Me What He Said”, a gossipy teen-beat American song written by Jeff Barry, with Helen quizzing friends about the actions of her ex-guy, and the touchingly slow “Little Miss Lonely” hit no.2 and no.8 respectively. The

‘Daily Mail Book Of Golden Discs’ says that ‘for a young singer she has dynamic drive and an inherent rhythmic sense with confidence, assurance and personality quite outstanding for her age.’ While her mentor – Norrie Paramor was satirically attacked by David Frost in a lengthy

‘That Was The Week That Was’ sketch for putting his own ‘ordinary’ compositions on ‘B’-sides by Helen – as well as Shane Fenton, and for writing Helen’s first non-Top Ten single ‘A’-side in late 1962 (“Let’s Talk About Love”).

If it was a mini-golden age of British Pop, it was also cosily insular and self-contained. With Norrie Paramor at the helm, the distinctive green Columbia label now had the triumvirate of Top Male singer in Cliff Richard, Top Group in the Shadows, and Top Female singer in Helen Shapiro. But although there were sales across Europe, and in English-speaking markets such as South Africa and Australia, none of the three names meant a light on the sprawling American music scene. The domestic record industry, with distribution controlled by a cartel of companies, also functioned in perfect symbiosis with a monolithic media. A Pop record featured on BBC’s ‘Juke Box Jury’ or ITV’s ‘Thank Your Lucky Stars’ got national viewer exposure, because they were the only two channels to watch. While, unless you could tune in to ‘Radio Luxembourg’s’ crackly evening reception, the BBC ‘Light Programme’ was the only radio place to hear Pop music, and then only rarely, on Brian Matthew’s ‘Saturday Club’ or on a request programme. While the music press and the fan magazines overflowing the newsagent counter colluded in promoting photogenic teen-stars. There was even a 1962 Annual-style

‘Helen Shapiro’s Own Book For Girls’.

The thumbnail narrative is that, after her span of hits, Helen was swept aside when this cosy consensus was blown apart by the Beatles-led Beat-Boom that first transfigured UK Pop in 1963, then went global in 1964. And although it’s true that Helen never fitted comfortably into the mini-skirt moppet Swingin’ Sixties pantheon of Cilla, Lulu, Sandie and Dusty, that interpretation is only partially true. The myth is irresistible because, at the beginning at 1963, she headlined a nationwide tour on which the nascent Beatles were the main support act, but that was already six months after her fifth and final top ten hit. Her hit-making days were already in decline when she began the tour at the Gaumont Cinema in Bradford on Saturday 2 February. On a six-act bill headed by Helen, the Beatles were openers. Their four-song set included “Please Please Me” – already on its way into the Top 3, as she was doing her current single “Queen For Tonight”, which barely scraped the Top 40.

Travelling in unceasingly cold weather Helen was forced to miss dates in Taunton and York due to flu. While the Beatles crowd into her dressing room to watch their latest ‘Thank Your Lucky Stars’ appearance because – as headliner, hers is the only dressing room equipped with a TV! Ever-alert to the possibility of promoting their own song-writing, John & Paul offer her “Misery” from the debut album they were still in the process of recording. She – or her management on her behalf, turned the song down, only for it to be snapped up by Kenny Lynch, who was also on the bill. It became his next single, and the Beatles first cover. By the final date – in Hanley on Sunday 3 March fan-hysteria had elevated the Beatles up the bill to closing the first half.

Few artists could have coped with the impact of that tour, least of all a teenage girl suddenly faced with the headline ‘Is Helen Shapiro A Has-Been At Sixteen’. For her Pop career never fully recovered. And how strange is that? To go from being taxi’d to school to avoid fans mobbing the playground gates. From having press photographers scale school drainpipes in attempts to obtain sneak through-the-window shots of her at her classroom desk. To being chaperoned on tours due to her under-age status. To missing out on normal teenage dating because every-day boys were in awe of her stardom. Then – just as abruptly, to be ruthlessly elbowed aside by rapidly-shifting trends. Faced with the same bewildering career switch-around, Frankie Lymon, who’d preceded Helen to the no.1 slot, died a junkie in his twenties. Yet for Helen there were no Britney-style dramatics or highly-publicised breakdowns.

There’s a video of Britney Spears lip-synching to a rigidly-disciplined highly-choreographed hit dance-routine. In the closing seconds she flashes the briefest of brittle smiles at the camera, less a smile of pleasure or satisfaction, and more a grimace of sheer relief that she’s got through the arduous shoot without messing up. To me, it betrays the human vulnerable pressures such young stars are subject to. It’s to her credit that Helen rode those seismic changes with dignity and grace. And went on to other things.

Having early shown a bias for ‘quality’ material, she moved her career solidly in other directions. She continued to appear in cabaret, to issue records for Pye, Magnet, Arista and DJM, while working and recording with jazzer Humphrey Lyttleton (between1984 and 2001). She remained very much in demand as an actress and singer. Then, in Autumn 2002 she did what was announced as her ‘Farewell Tour’, teaming up with ‘Special Guest’ Craig Douglas – her movie co-star from

‘It’s Trad Dad’, to perform her roster of Pop hits for the last time. On Sunday 3 November she played the intimate stage of the Leeds ‘City Varieties’ doing the ‘whoop-bah-oh-yeah-yeah’ of “Walkin’ Back To Happiness”, “Tell Me What He Said” and the smoky-slow drama of “You Don’t Know”. It’s a lifetime since she first hit with “Don’t Treat Me A Child”, but when she sings ‘gonna be my own adviser, ‘cos my mind’s my own’ tonight, you still catch something of the advance tremor of that Sixties Youthquake.

HELEN’S HITS

23 March 1961 – “Don’t Treat Me Like a Child” c/w “When I’m With You” (Columbia DB 4589) no.3 on charts for twenty weeks. ‘B’-side writer credits to Burman-Schroeder-Hawker

29 June 1961 – “You Don’t Know” c/w “Marvellous Lie” (Columbia DB 4670) no.1, on charts 23-weeks. ‘B’-side written by Norrie Paramor with Bunny Lewis

28 September 1961 – “Walkin’ Back To Happiness” c/w “Kiss ‘n’ Run” (Columbia DB 4715) no.1, on charts for 19-weeks. Spends a single week on the US Hot Hundred, at no.100. Vocal backing by the Mike Sammes Singers. ‘B’-side by Paramor/ Lewis

December

1961 – ‘

HELEN’ EP (Columbia SEG 8128) with Martin Slavin and his Orchestra, interpretation of standards, ‘Goody Goody’ which receives airplay, with ‘Tiptoe Through The Tulips’, ‘After You’ve Gone’ and ‘The Birth Of The Blues’ which she’d sung as part of her original audition demo

December 1961 – ‘

HELEN’S HIT PARADE’ EP (Columbia SEG 8136) collects ‘Don’t Treat Me Like A Child’, ‘You Don’t Know’, ‘Walkin’ Back To Happiness’ and ‘When I’m With You’

15 February 1962 – “Tell Me What He Said” c/w “I Apologise” (Columbia DB 4782) no.2, on charts 15-weeks. ‘A’-side written by Jeff Barry

10 March 1962 – ‘

TOPS WITH ME’ (Columbia 33SX 1397) LP, reaches no.2, on LP chart for 25-weeks. Sleeve-notes by ‘NME’s Maurice Kinn. With side one: ‘Little Devil’, ‘Will You Love Me Tomorrow’ (the Shirelles version on the chart the week ‘Don’t Treat Me Like Child’ debuts), ‘Because They’re Young’, ‘The Day The Rains Came’, ‘Are You Lonesome Tonight?’ (the Elvis version on the chart the week ‘Don’t Treat Me Like Child’ debuts), ‘Teenager In Love’, and side two: ‘Lipstick On Your Collar’, ‘Beyond The Sea’, ‘Sweet Nothins’’, ‘You Mean Ev’rything To Me’, ‘I Love You’, ‘You Got What It Takes’. First four tracks issued as EP ‘Tops With Me’ (SEG 8229), and second four as EP ‘Tops With Me no.2’ (SEG8243, 1963)

3 May 1962 – “Let’s Talk About Love” c/w “Sometime Yesterday” (Columbia DB 4824) no.23, on charts seven weeks. ‘Let’s Talk About Love’ featured in her film ‘It’s Trad Dad’ alongside ‘Ring-A-Ding’, a duet with co-star Craig Douglas

12 July 1962 – “Little Miss Lonely” c/w “I Don’t Care” (Columbia DB 4869) no.8, on charts 11 weeks. Return to Schroeder/ Hawker material

18 October 1962 – “Keep Away From Other Girls” c/w “Cry My Heart Out” (Columbia DB 4908) no.40, on charts six weeks. ‘A’-side is a Bacharach/ Hilliard song covered from the US Babs Tino version. Helen sings ‘B’-side (by Newell-Paramor) in cameo appearance in the Billy Fury film ‘Play It Cool’

7 February 1963 – “Queen For Tonight” c/w “Daddy Couldn’t Get Me One Of Those” (Columbia DB 4966) no.33, on charts five weeks

April 1963 – ‘

HELEN’S SIXTEEN’ LP (Columbia 33SX 1494), title refers to both her age, and the number of LP tracks. With Martin Slavin And His Orchestra. Side one: ‘Tearaway Johnny’, ‘Without Your Love’, ‘Walking In My Dreams’, ‘Who Is She’, ‘I Want To Be Happy’, ‘Time And Time Again’, ‘Aren’t You The Lucky One’, ‘Every One But The Right One’. Side two: ‘It’s Alright With Me’, ‘Lookin’ For My Heart’, ‘Basin Street Blues’, ‘You Must Be Reading My Mind’, ‘Till I Hear The Truth From You’, ‘Sensational’, ‘Easy Come Easy Go’, ‘I Believe In Love’

25 April 1963 – “Woe Is Me” c/w “I Walked Right In” (Columbia DB 7026) no.35, on charts six weeks. Recorded in Nashville

January 1963 – “Not Responsible” c/w “No Trespassing” (Columbia DB 7072) no chart position. Also recorded in Nashville

23 October 1963 – “Look Who It Is” c/w “I Walked Right In” (Columbia DB 7130) no.47, on charts 3 weeks. Introduced by DJ Keith Fordyce, Helen lip-synchs the song on ‘Ready Steady Go’, singing one verse apiece to Beatles John, Ringo and George, each of them shown from behind, turning as Helen reaches them

October 1963 – ‘

HELEN IN NASHVILLE’ LP (Columbia 33SX 1561) with Grady Martin and the Jordanaires. Side one: ‘Not Responsible’, ‘I Cried Myself To Sleep Last Night’, ‘Young Stranger’, ‘Here Today Gone Tomorrow’, ‘It’s My Party’ (Helen cuts the original version of this song, intended for single release until the Lesley Gore version appears), ‘No Trespassing’. Side two: ‘I’m Tickled Pink’, ‘I Walked Right In’, ‘Sweeter Than Sweet’, ‘You’d Think He Didn’t Know Me’, ‘When You Hurt Me, I Cried’, ‘Woe Is Me’

23 January 1964 – “Fever” c/w “Ole Father Time” (Columbia DB 7190) no.38, on charts for four weeks. Revival of Peggy Lee hit

1964 – “Look Over Your Shoulder” c/w “You Won’t Come Home” (Columbia DB 7266)

1964 – “Shop Around” c/w “He Knows How To Love Me” (Columbia DB 7340) cover of Smokey Robinson’s Miracles hit

1964 – “I Wish I’d Never Loved You” c/w “I Was Only Kidding” (Columbia DB 7395)

1965 – “Tomorrow Is Another Day” c/w “It’s So Funny I Could Cry” (Columbia DB 7517)

December 1966 – “In My Calendar” c/w “Empty House” (Columbia DB 8073), ‘Record Mirror’ says ‘best in a long-while, this, with Helen on a minute-kick, controlled number, very strong on lyrics, melodic and professional’

March 1967 – “Make Me Belong To You” c/w “The Way Of The World” (Columbia DB 8148) ‘Record Mirror’ says ‘wondrously big-voiced and swinging performance which really does deserve to do well.’ ‘NME’ agrees with ‘what does this lass have to do to get a hit?’ ‘B’-side is self-penned bossa-nova

March 1969 – “Today Has Been Cancelled” c/w “Face The Music” (Pye 7N17714), rejoining John Schroeder at new label, ‘NME’ says ‘poor old Helen Shapiro always seems to be on a hiding to nothing! A happy-go-lucky rhythmic ballad with a sparkling Latin beat… a bright blues-chaser’

February 1970 – “Take Down A Note, Miss Smith” c/w “Couldn’t You See” (Pye 7N17893) ‘NME’ says ‘Helen keeps trying, bless her heart… a lively finger-popper with a brassy backing and a hint of a Latin flavour. Plus a sing-along la-la chorus. Come on you dee-jays, give her a break!’

September 1974 – ‘

THE VERY BEST OF HELEN SHAPIRO’ LP (EMI SCX 6565) ‘NME’s Pete Erskine praises ‘an album that, by rights, should be prescribed, with natural orange juice and penicillin on the National Health… she howls like a waste-disposal unit on ‘Let’s Talk About Love’ and hums like a top on ‘Basin Street Blues’ One of many hits compilations

August 1977 – “Can’t Break The Habit” c/w “For All The Wrong Reasons” (Arista 131), a Russ Ballard song, ‘NME’ says ‘remember how deep her voice was? Well, it’s even deeper now’

March 1978 – “Every Little Bit Hurts” c/w “Touchin’ Wood” (Arista 178) ‘NME’ snipes ‘undistinguished version of the Brenda Holloway chestnut from 1963s favourite schoolgirl when the beehive barnet was all the go’

September 1991 – ‘

HUMPH & HELEN: I CAN’T GET STARTED’ LP (Calligraph CLG CD 025), billed as Helen Shapiro & Humphrey Lyttelton, following an earlier collaboration of ‘Echoes Of The Duke’, with ‘After You’ve Gone’, ‘The Music Goes Round And Round’ and ‘It Might As Well Rain Until September’

July 1998 – ‘

SWING, SWING TOGETHER… AGAIN’ LP (Calligraph CLG CD034), another collaboration with Humphrey Lyttelton, ‘Observer’ critic Dave Gelly commends ‘fifteen tracks cover everything from gospel to the Ink Spots’ and urges ‘listen out particularly for a gorgeous version of Duke Ellington’s ballad ‘All Too Soon’’ as Helen’s ‘singing blossoms in the environment of a good swing band’