DC THOMSON SPACE HEROES

‘ADVENTURE’ (no.1, 17 September 1921 – 1878 issues to 14 January 1961, when it merges with ‘Rover’) First of DC Thomson’s ‘Big 5’ story-papers. Includes Sci-fantasy text-serial tales:

‘

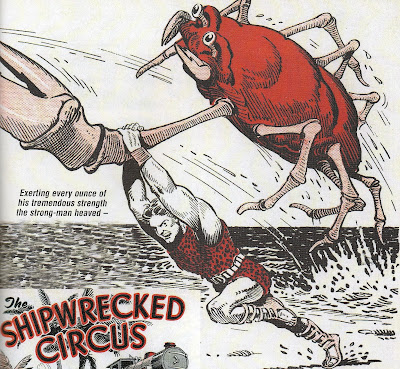

The Shipwrecked Circus’ (no.372, 15 December 1928), Samson’s Circus, recreated in ‘Beano’ in 1943, and with Pat Nicolle art for the 1958 ‘Beano Annual’

‘

Strang The Terrible’ (no.775, 5 September 1936, then no.963, 1940), cover-picture for no.1310 (25 February 1950) announces ‘Strang Is Back Today’, and a cover picture-strip story ‘Strang In The Underworld’ runs through 1951, relaunched in ‘Beano’ in (no.240, 9 September 1944 – 1945) with art by Dudley Watkins (page reproduced in ‘Great British Comics’ Aurum, 2006)

‘

Wardens Of The Worlds In Space’ (no.988, 5 October 1940)

‘

The City That Forgot’ (no.1088, 28 August 1943 – 12-parts, to no.1099) ‘What would happen if everybody in your town suddenly forgot everything they had ever learned?’ The city of Russell Boulder, is isolated by a landslide, when Dr Michael Wane and his dull-witted Lurch-like slave Sibbar, unleashes his ultra-shortwave radiation. Airman Billy Powell force-lands his plane in the city square, into scenes of madness as the citizens devolve into mindless animal behaviour, robbed of all their memories. The story returns ‘In Pictures’ from no.1452 (10 May 1952)

‘

The World Of Tomorrow’ (no.1100, 12 February 1944)

‘

They’ll Try It Again’ (no.1129, 24 March 1945 – 14-parts)

‘

Bull Raiders From The Red Orb’ (no.1130, 7 April 1945 – 17 parts to no.1143, 6 October 1945) ‘A Wild West Story A Million Miles From The Wild West!’ Professor Hamilton with four men from the Circle-7 Ranch in Texas pursue cattle-rustlers from the Red Orb, ‘one of the lesser-known planets, nearly a million miles away’ – unwittingly carrying fourteen-year-old stowaway Davie Baird with them. They use a crashed alien ship which the professor re-equips.

‘

The Lost Legion’ (1948), front-cover picture-strip (no voice-balloons), a Roman city in Africa located – as in H Rider Haggard, by a human-head-shaped mountain, where Jimmy’s father is held prisoner. Zulu Untala fights the Monster of the Lake and Gool’s Ape-Men

‘

Lost Warriors Of The Arctic’ (1949), front-cover strip, Chip discovers a Viking town inside a volcano crater

‘

Outcast Of The Incas’ (from no.1251, 11 December 1948), front-cover picture-strip

‘

The Bubble’ (from no.1405, 1 December 1951 – to no.1415, in 1952)

‘

Nick Swift Of The Planet Patrol’ (First Series – Picture Story, no. 1419, 29 March 1952 – 15-parts to no.1434, 12 July 1952) Captain Ulmo’s brain-visualiser shows pirates kidnapping slaves from Altair, led by Vaska, operating from Ettin, his luxurious hide-out. Scientist Terro uses remote-hypnotism to control Triton, Nick tricks him, but the pals are captured and put to work in the Trog’s plutonium-mines. When Nick risks his life to save a slave from a punishment sacrifice to a ‘fiercesome monster’, he is sentenced to become a ‘living statue’, but the father of the slave he rescued assists him. With Vaska supposedly imprisoned they head for Jupiter where they rescue Timos marooned in space. Inky pretends to be ‘black guardsman’ Gooka to infiltrate Venusian pirates, and bashes Vaska over the head with a spanner.

‘

Nick Swift Of The Planet Patrol’ (Second series – Picture Story, no. 1466, 21 February 1953 – 11-parts, to no.1476, 2 May 1953) On Veerdon’s weird ‘broken terrain of jagged smoking craters’ they sleep in ‘glass cigar’ sleeping bags and use a tregosaurous – ‘Come on Fido’ urges Nick, to smash their way into the spitting metal Tower. They then call off at planet Kardon en route to Frankel where – disguised in hoods and using a captured turb-car, they penetrate the mystery city from which Vaska is projecting his ‘destroyer beam’

‘

Nick Swift Of The Planet Patrol’ (Third series – Text Story, no. 1488, 21 July 1953 – 14-parts, to no.1501, 24 October 24th 1953) Charb the Martian prospector, is the sole survivor of the petrifying-ray attack on Asteroid 37, the light he saw in the sky directs Nick towards Nebula 14. Galaxion demands sole monopoly of interplanetary trade and the disbanding of the Interstellar Police. Disguised as a Venusian by the ‘green lotion he always carried with him’ Nick enters the domed city to sabotage the space-tyrant’s power-room. Next, the ‘sinister master-brain’ turns his ray on planetoid refueling station Communa operated by Scots Director Ramsay. Characters are introduced, just to be killed off, Mutus is killed when Nick attempts to warn Communa. Then Lieutenant Gruk – leader of a force of Martian cops dispatched to aid Nick, is destroyed by the mutinous crew of a giant Venusian battle cruiser (towing an ‘artificial sun’) which is in league with Galaxion. Then Captain Rollin who leads the relief force is killed as the Space Cops breach Galaxion’s dome.

‘

Nick Swift Of The Planet Patrol’ (Fourth series – Picture Story, no. 1568, 5 February 1955 – 22-parts, to no.1589, 2 July 1955) Landing in Hespia, Logan checks out the atmosphere-analyser, and, although ‘there’s a pretty high argon content’ it’s breatheable.

‘ROVER’ (no.1, 4 March 1922 – 1961) includes

‘

Invisible Dick’ (no.1), serial about ancient bronze Egyptian invisibility relic, later revived for no.1 of ‘Dandy’

‘

Morgyn The Mighty’ (no.304, 11 February 1928, re-launched for a 14-part strip-tale in ‘Beano’ no.1, 30 July 1938, with art by George ‘Dod’ Anderson. There was also a 214-page one-off ‘Morgyn The Mighty’ storybook in September 1951, drawn by Dudley D Watkins. (page reproduced in ‘Great British Comics’ Aurum, 2006). A further strip series for ‘Victor’ from January 1965, with Ted Kearon art

‘

The Black Sapper’ (no.384, 24 August 1929), revived in ‘Beezer’ in 1959, and later still in ‘Hotspur’ 1971-1973

‘

Jimmy & His Grockle’ (1932), a giant egg from Jimmy Johnson’s Uncle Bill in South American hatches into the dragon-like ‘queerest beast to walk on land’, revived in picture-form for ‘Dandy no.1’

‘

The Purple Planet Needs Air’ (no.1078, 4th March 1944 to no.1102, 3rd February 1945) 14-part text-serial in which 6 ft tall aliens with metal bodies and their brains in a glass bowl set up giant suction machines which begin stealing the Earth’s atmosphere. The alien leader is ‘The Brain’, who is 9 ft tall and has a golden body. An expedition from Earth puts paid to their threat

‘

The Big Tree’ (no.1125 to 1134, 1945 to 1946), ten parts. An expedition to a 3,000ft tall tree in Kenya is attacked by savage primitive Tree-Men, giant bats and monster caterpillars. Re-run as a picture-strip in ‘Wizard’ as late as 1974, last part 1 June

‘

The Wonder Man’ (no.1132, 30 March 1946, and returns for four series, adapted as a strip it continued in ‘Victor’ from 1961-1962, then ‘Bullet’ from no.2, 21 February 1976 with Art by Tony Harding)

‘

Tough Of The Track’ (1949), welder’s apprentice at Greystone, Alf Tupper begins his running career

‘

Experiment X’ (3 September 1949 no.1262 – 12-parts, to no.1273)

‘

The Ninety-Nine Deadly Days’ (25 February 1950 no.1276 – 12-parts, to no.1287)

‘

The Menace In Pit 19’ (from 8 July 1950 no.1306 – 8 parts, to no.1313) trapped miners in Cragsbank Colliery encounter giant moles

‘

The Purple Planet’ (from 9 February 1952 no.1389, to no.1406, 7 June 1952) text-story sequel to ‘Rover’ story from 1944

‘

I Flew With Braddock’ (2 August 1952 no.1414), aerial narrative of Matt Braddock, ‘Britain’s Greatest Pilot Of The Second World War’ Bomber Command as supposedly told by Braddock’s navigator ‘George Bourne’. In reality, although uncredited, it was most likely written by Gilbert Lawford Dalton. Revived in picture-strip form in 1961 for launch issue of ‘Victor’

‘

Raiders From The Red Planet’ (from 13 September 1952 no.1420, 14-parts to no.1433)

‘

Return From Mars’ (from 3 January 1953 no.1444, 13-parts to no.1456) ‘Zero hour approaches! The armada of spaceships is ready to leave Mars for the invasion of the Earth!’ Mitch Fane returns from the Mars colony founded by British emigrants in 1954 to deal with invading Sarrians

‘

The Days Of The Dinosaurs’ (from 18 December 1954 no.1538, 12-parts to no.1549) Scientists discover a hidden realm beneath a Scottish Loch

‘

The Deadly Days Of The Capsids’ (22 October 1955 no.1582, 12-parts to no.1593) Aliens land in Britain

‘

Escape From The Moon’ (from 4 February 1956 no.1597, 10-parts to no.1606)

‘

The Miracle Man From Mars’ (from 10 November 1956 no.1637, 6-parts to no.1642)

‘

The Barrow-Boy From Mars’ (from 28 September 1957 no.1683, 7-parts to no.1689) Mrs Tyzssh tries to sell Martian food to Earth-people

‘

The Frightened Year Of The Fireflies’ (15 February 1958 no.1703, 15-parts to no.1717, 24 May 1958) with Britain invaded by an Eastern power

‘ROVER & ADVENTURE’

‘

The Thing From Outer Space’ (17 March 1962) through to May

‘WIZARD’ (no.1, 23 September 1922 – 1963 Final issue no.1970, 16 November 1963) when it was merged with ‘Rover’, re-launched 14 February 1970 as a Picture-Paper, until 10 June 1978 (no.435) when it was merged with ‘Victor’)

‘

The Wolf Of Kabul’ (January 1930), in the North-West Frontier of British-ruled India, Bill Sampson battles alongside cricket-bat wielding faithful servant Chung. Revived into 1961 ‘Hotspur’ picture-strip

‘

The Smasher’ (no.439, 2 May 1931), Doctor Doom’s robot would be revived for ‘Dandy’ in 1938, then ‘Victor’ and ‘Bullet’

‘

The Fires Beneath The Desert’ (no.1037, 13 November 1943 – 12-parts, to no.1048)

‘

The Truth About Wilson’ (no.1069, 24 July 1943) William Wilson from the Yorkshire Moors runs the four-minute-mile barefoot, in 3.48-minutes! Legendary character revived in ‘Hornet’ in 1964

‘

Crimson Comet’ (no.1108, 3 August 1946 – 13-parts, to no.1120)

‘

There Was Once A Game Called Football’ (1948) – set in the year 2148!

‘

I Saw The End Of The World’ (no.1325, 7 July 1951 – 8-parts, to no.1332, 25 August)

‘

The Monster In Hyde Park’ (no.1381, 2 August 1952 – to no.1388) A giant plant

‘

Boyhood Of Desperate Dan’ (no.1492, 18 September 1954) text-tales of ‘Dandy’ tough-guy!

‘

Bash Street School’ (4 June 1955) text-tales of ‘Beano’ kids!

‘

Hands Off The Purple Planet’ (no.1713, 13 December 1958) Complete Text Story

‘

The Ace Of Space’ (10 October 1959, no.1756 – no.1768) Matt Braddock was the ace Bomber Command RAF pilot of the ‘I Flew With Braddock’ World War II text-tales in ‘Rover’ since 1952. He cameos in this text-serial set in the future-year late Spring of 1961, but the central character is his young test-pilot nephew Norman who launches from the White Sands ‘ultra-modern rocket base’ of El Tusa, New Mexico as part of the US-Brit space programme – a joint UK/USA mission headlined in his local newspaper as ‘Walsall Man May Fly Round Moon’. The familiar Braddock connection is presumably there to ease readers into this cautious SF tale.

‘SKIPPER’ (no.1, 6 September 1930 – 1941) publication ‘temporarily’ suspended due to war-time paper shortages, but never revived

‘

The Boy Who Slept 100 Years’ (no.182, 24 February 1934 – 25-parts, to no.206)

‘

Britain Down – But Never Out’ (no.340, 6 March 1937 – 13-parts, to no.352)

‘

The Hairy Sheriff’ (1940)

‘HOTSPUR’ (no.1, 2 September 1933 – 17 October 1959 when it’s re-launched as a Picture-Paper, to be finally merged into ‘Victor’ in 24 January 1981) featured ‘Red Circle’ school stories. Includes Sci-fantasy text-serial tales:

‘

At School In 1975’ (no.164, 17 October 1936 to no.175, 2 January 1937) Mr Spud – former Fourth Form Master, but since automation and television-teaching, he has become Caretaker of Bankfield School

‘

Last Rocket To Venus’ (from no.313, 26 August 1939)

‘

Lost School On The Whirling Planet’ (from no.389, 8 February 1941, to June 1941)

‘

The Iron Teacher Speaks’ (no.412, 19 July 1941), returns no.716 (29 July 1950) with ‘The Iron Teacher vs A Sabre-Toothed Tiger’, then revived in 1959 as a picture-strip in revamped ‘Hotspur’ (no.691, 13 January 1973)

‘

The Amazing Adventures Of Three Boys On The Moon’ (from no.433, 14 March 1942), dramatic cover-art of winged spaceship approaching the Moon

‘

Space Detective’ (no.725, 30 September – no.732, 18 November 1950)

‘

Captain Zoom: The Ace Of Space’ (no.770, 11 August 1951, for 28-parts) This ‘Great New Jet-Propelled Flying Story’ was actually a reconfiguration of ‘Captain Zoom: Birdman Of The RAF’, a WW2-story from ‘The Skipper’ (from no.512, 22 June 1940). Now a simplistic cover picture-strip with captions but no voice-balloons, it stars Zoom who has rotors on his helmet, with other character-names such as Zek & Zipp, plus robotic adversaries

‘

Johnny Jett: The Super-Boy’ (no.782, 3 November 1951) ‘A Great New Story Told In Pictures’. Shipwrecked as a child on Signal Island, Johnny is brought up by scientist Samuel Holmes. He would adventure again from the first issue of ‘The New Hotspur’ (24 October 1959).

‘

Neptune’s Chimney’ (no.827, 13 September 1952 – 6-parts, to 832)

‘

Slaves Of The Machine’ (no.864, 23 May – no.873, 1 August 1953)

‘

S.O.S From Planet X’ (no.923, 17 July 1954 – 12-parts, to no.934), the cover for no.933 – 25 September, shows ‘The Snake’, an Earthling turned interstellar gangster’ who ‘Leaves A trail Of Terror In The Great Space Story’. Also a banner announcing ‘Leatherface Is Back In A Great Picture-Story!’

‘

The Men Who Lived Twice’ (no.1060, 2 March 1957) followed by sequel ‘The Man Who Lived Three Times’ from no.1067, 20 April

‘DANDY’ (founded by Albert Barnes, formerly of ‘Hotspur’, no.1 4 December 1937, with free ‘Express Whistler’, and ‘Korky The Cat’ cover-story by James Crichton, a position he holds until 10 November 1984. ‘Freddy The Fearless Fly’ by Allan Morley is also in the first 667-issues). No.1 also includes ‘Keyhole Kate’, ‘Desperate Dan’, ‘Barney Boko’, ‘Sammy And His Sister’, ‘Hungry Horace’, ‘Magic Mike And His Magic Shop,’, ‘Smarty Grandpa’, an ‘Our Gang’ strip based on the MGM Hal Roach film-characters, picture-strip Western ‘The Daring Deeds Of Buck Wilson’, plus text-tales ‘The Tricks Of Tommy’, ‘Red Hoof: The Great Story Of A Boy And A Young Stag’, ‘The Magic Sword: The Story Of A Boy Sent To Fight A Tyrant King’, ‘Wee Tusky: The Thrilling Jungle Like Of A Baby Elephant’, ‘When The West Was Wild’ (‘Jumping Frog’ ad for gift in no.2), and back-page ‘Bamboo Town’

‘

Lost On The Mountain Of Fear’ (no.1, to 1939), plane-wrecked on an Andean plateau Major Bryant and children Peter and Patricia are saved by manservant Handy Clark who defies giant spiders to reach a Lost City. He returns versus Nigerian giants in ‘Handy Clark On The Treasure Trail’, by Fred Sturrock

‘

Invisible Dick’ (no.1, to 1939), revived from 1922 ‘Rover’ serial about ancient bronze Egyptian invisibility relic. By George Ramsbottom

‘

Jimmy And His Grockle’ (no.1, to 1939), revived in picture-form from 1932 ‘Rover’ text-story. A giant egg from Jimmy Johnson’s Uncle Bill in South American hatches into the dragon-like ‘queerest beast to walk on land’, by James Clark. Revived yet again for ‘Sparky’ 1966 to 1976

‘

The Smasher’ (no.39, 27 August 1938), Dr Doom’s robot revived from ‘Wizard’ (1931), then by ‘Victor’ in 1962

‘

The Boy With The Iron Hands’ (no.90, 19 August 1939, to 1940), the saga of super-strong David who, with the Sword of Truth, overthrows the tyrant King Roderick the Red of the city of Albion in the mythic Caledon, art by Fred Sturrock

‘

Our Teacher’s A Walrus’ (1939)

‘

Little White Chief Of The Cherokees’ (1939 to 1941), fantasy-Western in which presumed-dead Harry Martin is adopted by Native Americans, only to face the Grim Dwarf and the otter-skinned Lord Of The Big-Sea Water, art by George Ramsbottom

‘

Jak The Dragon-Killer’ (1941), semi-mythic saga of mighty eight-foot-tall Tracian Jak who must slay a trail of monsters to rescue his three sons kidnapped by the King of Turkan, by James Fisher

‘

Peter Pye’ (1942), Dudley Watkins’ charming tale of a poor woodcutter’s son who becomes Chief Chef for King Francis II, assisted by the magical utensils of the jolly dwarfs of the forest, story reprinted in ‘Beano & Dandy: A Library Of Laughs’ (DC Thomson, 2000)

‘

King Of The Jungle’ (1943), animal-tracker Bill King with the vaguely fantastic element of a golden-tusked element, and a quest for the Missing Link, by James Clark

‘

Black Bob’ (no.280, 25 November 1944) in the wake of the successful ‘Lassie’ cinema-movies, ‘The Wisest Sheepdog In Scotland’ begins as text tales (one from 18 August 1945 reprinted in ‘Beano and Dandy: Favourites From The 40’s’, DC Thomson, 2003), new story no.519 (3 November 1951), text until 9 October 1955, resumes as picture-strip ‘WELCOME BACK! To Your Famous Old Pal, The Cleverest Collie In Britain’ (page reproduced in ‘Great British Comics’ Aurum, 2006). Drawn by Jack Prout in both versions. Bob visits Canada in 1964, hunts for missing Jimmy Glenn in Holland, rescues the kidnapped twin sons of a millionaire called Tucker, befriends circus poodle Lulu, and takes a 14-page Australian trip in 1976 (reprinted in ‘Beano and Dandy: Around The World In 60 Years’ (DC Thomson, 1998). Selkirk shepherd Andrew Glenn with his wonder-dog Border Collie also feature in DC Thomson’s ‘Weekly News’ (5 October 1946 – 3 March 1967), and continues in ‘Dandy’ until 24 July 1982. Full feature with reprint stories in ‘Beano and Dandy: Crazy About Creatures’ (DC Thomson anthology) Also in ‘Classics From The Comics no.7’

‘

The Amazing Mr X’ (1944), Len Manners, ‘a big loosely-built private inquiry agent’, assumes the secret identity of the first all-British caped superhero in ‘a queer costume, black skin-tight trousers and white jersey, with a flowing black cloak and black mask’. No real super-powers although ‘hidden powers seemed to surge through his body’ giving him ‘amazing strength’. When an escaping rail-crook unhooks the carriages of a speeding train Mr X ‘grabbed the connecting link’ and ‘exerting all his strength… pulled the two carriages together and closed the catch’. Wow! Art by Jack Glass (story in ‘Classics From The Comics no.17’)

‘

Danny Longlegs’ (no.286, 3 February 1945, to 1950), Danny Kettle,‘he’s ten-feet tall and up to the ears in trouble!’ in medieval Sleepy Valley, by Dudley Watkins. He returns to ‘Dandy’ in 1962 with crafty circus-scout Clem Davis from Boulder City trying to sign him up (one tale reprinted in ‘Beano and Dandy: Side By Side’, DC Thomson, 1999)

‘

Wuzzy Wiz – Magic Is His Biz’ (no.369, 21 May 1949 to 1955) Bill Holroyd illustrates the comic tales of this bungling medieval magician. Reprinted in ‘Beano and Dandy: History Of Fun’ (DC Thomson, 2001)

‘

Sir Solomon Snoozer’ (no.408, 17 September 1949 to 1950), the Red Knight with horse Ribshanks and page Robin O’Dare entombed in a medieval cave, revived for comical japes in the modern world, Paddy Brennan’s first art-work of DC Thomson. ‘Gadzooks!’ (panels reprinted in ‘Beano and Dandy: Crazy About Creatures’)

‘

Lion Boy’ (13 August 1949 to 22 April 1950), jungle-boy Raboo is captured and sold to Martin’s Mammoth Circus in the USA, he escapes with his lion and heads for his African home, art by Jack Glass

‘BEANO’ (founded by George Moonie, formerly of ‘Hotspur’ and ‘Wizard’, no.1, 30 July 1938, with Reg Carter’s comic ostrich ‘Big Eggo’ as cover-story for the first 326-issues. In June 1988 a copy of ‘Beano no.1’ was auctioned in Edinburgh for £825)

‘

Morgyn The Mighty’ (no.1, 1938), strip-adaptation of ‘Rover’s ‘Strongest Man In The World’, with art by Kearon. Later revived in ‘Victor’ in 1963

‘

Tom Thumb’ (no.1, as text tales, then 1941 to 1958) ‘the brave little one’ six-inch hero rides Peterkin the Cat through medieval England, with curly-haired black friend Tinkel and text-boxes in rhyme, one from November 1946 reprinted in ‘Beano and Dandy: Favourites From The 40’s’, DC Thomson, 2003. Art by Dudley D Watkins. Later in ‘Bimbo’ (1961 to 1969) and ‘Little Star’ (1973 to 1975)

‘

Here Comes Ping The Elastic Man’ (no.1, to 1940) comical rhyming romps from Hugh McNeill

‘

Wild Boy Of The Woods’ (no.1, to 1942, then 1947-1949), feral boy lives in a secret cave entered through a hollow tree, with old hermit called Grandfather, in the woods near Barchester, art by Toby Baines

‘

Tin-Can Tommy: The Clockwork Boy’ (1938) in May 1942 the tin boy comically foils a Nazi agent, story reprinted in ‘Beano and Dandy: Favourites From The 40’s’ (DC Thomson, 2003)

‘

The Shipwrecked Circus’ (no.200, text-tales 27 February 1943 to 1947, picture-strips 1951 to 1958), revived from early ‘Adventure’, when the ‘Margo’ sinks, the Circus performers are stranded on the South Sea Crusoe Island – leopardskin-clad strongman Samson, Trixie the Bareback Rider, Danny the young acrobat, Gloopy the dwarf clown and Horace the cigar-chomping educated ape. Strips reprinted in ‘Beano and Dandy: Focus On The Fifties’ (DC Thomson, 2004) and ‘Beano and Dandy: Around The World In 60 Years’ (DC Thomson, 1998). Artist Paddy Brennan later created ‘Showboat Circus’ for ‘Beezer’ with leopardskin-clad strongman Big Jim Sullivan’s circus sailing the Mississippi in the 1840s on the ‘Southern Belle’

‘

Jimmy And His Magic Patch’ (no.222, 1 January 1944, first series to no.239, then to 1949, Art: Dudley Watkins. Art by Paddy Brennan 1950 to 1951, and 1959, with many reprints including in ‘Classics From The Comics’), he frees Roman and Carthaginian galley-slaves (1944), joins ‘Strang The Terrible’ (3 June 1944, the episode reprinted in ‘Beano and Dandy: Side By Side’, DC Thomson, 1999), visits Delhi for the Indian Mutiny (1946), William Tell (1946), Nero’s amphitheatre (1946), Japan ‘where ju-jitsu was first taught’ (1946), the Great Fire of London (1948), Ali Baba (24 January/ 7 February 1948), with baby cousin Ernie in Lilliput (1948, reprinted in ‘Beano and Dandy: Favourites From The 40’s’, DC Thomson, 2003), a jousting tournament with Sir Gerard vs The Black Knight (1949), Sir Lancelot (13 August 1955), King Canute (17 August 1957), with Horatius defending Rome from Lars Porsenna’s Etruscans (1959), uses the lawn-roller to help cave-boys escape a Tyrannosaurus (1959), he becomes a 19th Century chimney Sweep (1960), the Charge of the Light Brigade with Florence Nightingale, and Felix the family cat helps him when Phoenician traders are attacked by Moorish pirates

‘

Strang The Terrible’ (no.240, 9 September 1944, to 1945) Dudley Watkins picture-strip version of original ‘Adventure’ text-tales. Strang guests in a ‘Jimmy & His Magic Patch’ tale dated 3 June 1944 (reprinted in ‘Beano and Dandy: Side By Side’, DC Thomson, 1999). Feature and strip – Strang tangles with King Agar and Kark the High Priest in the Lost City, in ‘Beano: 70 Years Of Fun’ (DC Thomson, August 2008)

‘

The Horse That Jack Built’ (1949), with a highly unlikely medieval premise young Jack London has a robot ‘clockwork’ horse with telescopic legs which he rides to outwit Baron Grimface (reprinted in ‘Beano And Dandy: Favourites From The 40’s’, DC Thomson, 2003), and an ejector saddle when he faces pirates on the Golden Hawk in November 1956 (reprinted in ‘Beano And Dandy: Focus On The Fifties’, DC Thomson, 2004)

‘

Jack Flash’ (no.355, 19 February 1949 to 1958), ‘Out in the inky blackness of space, against a background of whirling planets, a strange machine hurtled at lightning speed towards the Earth…’, the son of the planet Mercury’s top scientist takes Dad’s snub-nosed rocket-ship, ‘of a kind that even scientists on Earth had only dreamed about’. It crashes into the English Channel off the south coast. Like the mythological Mercury he has winged heels which allow him to fly and commit minor naughty-step mischief. Art by Dudley Watkins, and then (from 1955) by Paddy Brennan. Lived again in ‘Mandy’ – as Jackie Flash (1973), and ‘Nutty’ (1980), strip reprinted in ‘Beano And Dandy: Around The World In 60 Years’ (DC Thomson, 1998). That the Rolling Stones had a hit record with “Jumping Jack Flash” is perhaps purely coincidental

‘MAGIC’ (22 July 1939 to 25 January 1941. With cover-star ‘Koko The Pup’, its 80-issues were ended by the war-time paper shortages that also forced ‘Beano’ and ‘Dandy’ to alternate on fortnightly schedules)

‘

The Seven-Foot Cowboy’ (no.1, 1939), good-natured Sheriff of Boulder Gap, art by James Walker

‘

Gulliver’ (no.61, 1940), Dudley Watkins takes comic liberties adapting Dean Swift’s classic tale

‘

Beric The Cave-Boy’ (1940), ten-thousand years ago ‘long before civilisation had come to Britain’, Beric’s family compete with dinosaurs for a cave to live in, art by James Walker

With grateful thanks to Vic Whittle’s wonderful website