TIM HARDIN:

THE REAL

‘BEAUTIFUL LOSER’

The life, death, hard times and hits of the

man

who wrote “If I Were A Carpenter”

REASONS TO BELIEVE

Tim Hardin had simplicity. Songs sparsely-worded, stripped down to haiku-like equations. Slight chord progressions, out of Blues, built up in neat clusters, the juxtaposition of phrases systematically and frugally rearranged as if by mathematical principles into different combinations, different songs, until the variation-possibilities were exhausted. Songs that, like all good Blues, were admirably suited to jazz improvisation.

Not for Tim Hardin the epic methedrine-scrambled ‘Desolation Row’ odysseys of a Bob Dylan. Not for Tim Hardin the artfully literate postures of a Leonard Cohen, or the agit-prop radicalism if a Phil Ochs. Not for Tim Hardin the fey art nouveau fairy tales of a Donovan. Like Michael Zwerin puts it in the liner-notes for

‘Tim Hardin 3’ (1968), ‘each version of “Misty Roses” is like alternate takes by Charlie Parker. Fresh and different.’

But if Tim Hardin was really ‘kissed by a fast-flying muse’ as

‘Q’ journalist John Bauldie suggests, that muse finally ran out 29 December 1980. Hardin died of an overdose in his Hollywood Orange Drive apartment just three weeks after the John Lennon shooting, leaving only a slender line of immaculate songs.

Tim Hardin was a descendent of the legendary ‘guiltless outlaw’ John Wesley Hardin about whom Bob Dylan created a mythology. He was born in Eugene, Oregon 23 December 1940, and began pursuing his music muse in earnest following his discharge from the US Marines in 1961, after seeing voluntary action in Vietnam, and picking up a taste for heroin there around 1958. He played in Boston Folk Clubs, studied acting for a while in New York, even taught guitar for a semester (a term) at Harvard. Inevitably, by 1964 he’d gravitated to bohemian Greenwich Village to play the legendary ‘Night Own Café’, then the melting pot of new styles and influences. The Mamas and the Papas retrospected its significance on their hit single “Creeque Alley”, and Lovin’ Spoonful named a searing Blues instrumental after the café.

Hardin’s music, a deft and personal fusion of Blue simplicity, Jazz eloquence and Folk purity, was showcased at the 1966 Newport Folk Festival which went some way towards establishing him as a performer and a writer of note. Tapes recorded and subsequently forgotten, made during this period, surfaced much later as the

‘This Is Tim Hardin’ (1967) LP – although there are claims they were actually made as early as 1963-64. The set shows him drawing heavily on traditional material, “Hoochie Coochie Man”, “Stagger Lee” and “House Of The Rising Sun”, but there are also four of his own early songs including “You Got To Have More Than One Woman”, and the much-recorded “Danville Dame” which has him reworking standard Beat Hobo imagery – ‘I’m riding a flat car, flat on my back…’, into a contagiously shuffling rhythmic pattern already idiosyncratic and uniquely Hardinesque. Both songs were later to become a standard part of his stage act. Yet at the same time he was also stockpiling a number of incandescent and startlingly original compositions for his first official album.

He made some demonstration tapes, which Charlie Koppleman hawked around US Columbia (CBS in England). They got him as far as working in the studio with a Columbia staff producer, but nothing came of the sessions and he took his tapes, instead, to Verve. Those initial demo’s were later used, according to Hardin, ‘in direct breach of contract’ by the label – but in the meantime he worked on tracks for his debut album.

‘Tim Hardin 1’ was issued in September 1966. It was, according to Rock Encyclopaedist Lillian Roxon, two years in the making – a reference to its inclusion of two early songs, but even if taken at face value, then not a second of that time can have been wasted. Decades later the simple insistence of songs like “Don’t Make Promises”, “Reason To Believe” and “Misty Roses” retain the power to amaze. Phil Hardy and Dave Laing comment that ‘his style was maturely formed, owing more to Jazz and Blues than Folk. He used his emotionally-charged voice as a musical instrument’ (

‘Encyclopedia Of Rock Vol.2’). The voice is brittle, cracking in around the lines, the instrumentation sparse – although Gary Burton’s Jazz vibraphone adds tone and texture, as do John Sebastian’s harmonica and Felix Pappalardi (later a producer for Cream and member of Mountain). The strings were overdubbed without Hardin’s consent, and – it was later made clear, at his express displeasure. But occasionally, as on “Hang Onto A Dream”, the strings are quite within context and work a lot better than one could logically expect them to.

The sleeve is an unflatteringly realistic head-shot of Hardin taken in the garden of the ‘Castle’, a square-faced, solid figure. None of the overstated poetic contrivances of a Tim Buckley or a Bob Dylan ‘Blonde On Blonde’ shot. By contrast, Hardin could be a labourer, a stonemason – or a carpenter. He appears to be of the earth, unaffected and real.

In a later interview with Michael Watts, Hardin explains that the words for his songs come first, as poems – ‘the lyrics are the rhythmic scheme. The words make the line of the melody because I sing improvisationally’ (

‘Melody Maker’ March 1972). And the voice, its conviction reinforcing rather than belying his appearance, is often apologetic, vulnerable. A voice at once containing melancholia and desolation through a naturally extemporised fluidity that never once resorts to any kind of unnecessary theatricality.

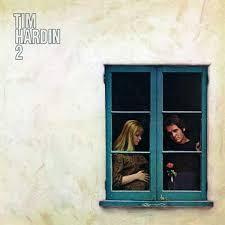

Barely nine months later, Hardin delivered the second instalment,

‘Tim Hardin 2’ (1967) which consolidated all the critical expectations. Here is “If I Were A Carpenter”, “Black Sheep Boy”, “Lady Came From Baltimore” and “You Upset The Grace Of living When You Lie”. If Hardin had never again set foot in the studio his stature would be assured by just these two records. Eric Jacobson, an ex-Folkie who later did production work for Sopwith Camel and Norman Greenbaum’s “Spirit In The Sky”, had produced

‘1’, and went on to arrange

‘2’, while Charlie Koppleman and Don Rubin take producer credits this second time round. In the guise of Kama Sutra records Jacobson, Rubin and Koppleman also launched and financed Lovin’ Spoonful.

But in the meantime, as well as being integrated albums in their own right, Hardin’s two sets of original songs quickly became the most successful ‘demo’ discs of the period. Seldom can so few songs have been covered by so many artists. Bobby Darin was the first. Apparently he’d been offered John Sebastian’s “Do You Believe In Magic?”, but turned it down as ‘too weird’. Following its immense chart success for the Spoonful, Darin was anxious to avoid repeating such an unfortunate choice, and agreed to accept and record whatever Folk-orientated material the agency next offered him. Hence he cut “If I Were A Carpenter” before the release of Hardin’s own version, tightening and sharpening the arrangement, but leaving the song’s essence admirably intact. His reading of the song so close to the original that an anguished Tim was reported as protesting ‘he’s stolen my voice!’ The single became a monster hit on both sides of the Atlantic, peaking in the States at no.8 and no.9 in Britain during November 1966.

‘If I were carpenter, and you were a lady, would you marry me anyway, would you have my baby.’ The lyric strips human relationships back to raw basics, relinquishing status and class, to the most fundamental man-woman bond. And it’s mature adult love, to do with family and procreation, not teeny Pop-fodder. If he was a miller ‘with the mill-wheel grinding’, or a tinker ‘carrying the pots I’d made’… true traditional craft-occupations with medieval roots into the hard-grit certainties of an almost lost reality. At a time of fierce revolutionary gender politics it could be argued the song cleaves to the ‘when Adam delved and Eve span’ archetype, he the artisan-provider, she the pregnant Earth-mother, but such a reduction carries its own prima truth. Each line is the purest romantic poetry, sparsely-worded statements, pared down to haiku-like equations, Tim Hardin had the gift of simplicity.

Darin went on to record an impressive “Lady Came From Baltimore” too, as did Scott Walker and Joan Baez. Rod Stewart did a well-intentioned but clumsy “Reason To Believe”, his first-ever chart hit – no.19 in September 1971, Johnny Mathis also did a bland MOR version of the same song. “Hang Onto A Dream” was recorded by Cliff Richard and Keith Emerson’s Nice. “Don’t Make Promises” came via Lulu, a 1967 A-side from Timebox, and by the Sandpipers. “It’ll Never Happen Again” by Cilla Black… while further covers of “If I Were a Carpenter” appeared by the Four Tops – Top Ten in March 1968, and Johnny Cash. Hardin even had mild chart success with his own single of “Hang Onto A Dream” c/w “Reason To Believe” which reached no.38 on the UK ‘Disc’ chart (21 January 1967). First time I heard the song I was driving in my first mini, I slowed into the roadside to stop and listen until each note had faded, transfixed by its toe-curlingly delicate beauty. I bought the album that same week.

The ripple climaxed the following July 17, when Tim sold out the Royal Albert Hall, playing to an audience that not only included Donovan, but various Beatles and Rolling Stones too.

It seems incredible that a talent capable of creating such stunning first statements would be unable to follow their success. All the best songs for both albums had been written during one eight-month period – according to a

‘Melody Maker’ interview (26 January 1974), and yet a later

‘Best Of Tim Hardin’ (1969) compilation was, with some justification, made up of material exclusively taken from just these two sets. It could be suggested that the impasse lay in the basic simplicity of the formula – that all its possible variations ha been exhausted.

It’s also true that later recordings became more structured in production terms, and that Hardin himself repeatedly downgraded his own skills as a writer – preferring to see himself as a performer and interpreter of material. Yet the fact of creative decline is escapable. There are mitigating personal problems, most immediately a bout of bad health that took him through a recuperation stay in Colorado. Throughout this time he suffered from bad respiratory ailments, from pleurisy, and other unfortunate effects of his heroin habit, which he temporarily kicked through a sleep cure in 1968 following an abortive British tour down-bill of Family.

There were also complications with Hardin’s contractual ties to Verve. He signed to CBS in 1968, but before being able to release original work through this new hook-up, his commitment to Verve had to be fulfilled. Hence a few ‘contract filler’ albums emerged.

‘Tim Hardin 3’ is in-concert material, but although largely a live hits collection, it remains a mesmerising performance, from the sleeve-notes revealing that ‘drummer (Donald) McDonald wore bells around his neck which, from time to time, can be heard on the album,’ right down to the performance of “Song For Lenny” written on hearing of Lenny Bruce’s death. Hardin had known the iconoclastic comedian in New York – and the song, poignantly stating ‘never again will we be together to die,’ was born immediately after Tim had returned from a Newport Festival gig to be told the news. Tim also contributes to the

‘Why Did Lenny Bruce Die?’ spoken-word album (1966, Capitol KAO 2630).

A further song tributes another tragic hero, Amerikana pioneer Hank Williams – ‘whisky took the heartbreak from too many broken dreams, and what pain wasn’t cured by whisky was cured by too much morphine’. Shot through with hurt, the song concludes prophetically ‘I didn’t know you, but I’ve been the places you’ve been.’ The album was recorded during a 10 April 1968 concert at the New York Town Hall, one of his first gigs to follow his Colorado recuperation. It also features his ‘perfect’ band – McDonald on drums, Warren Bernhardt doubling on piano and clarinet, Daniel Honkin on guitar, plus Eddie Gomez (bass) and Mike Manier (vibes).

‘Tim Hardin 4’ (February 1969) has a more complex history, made up of excerpts from the demonstration tapes recorded prior to the Verve contract, material – according to

‘ZigZag no.43’, dating from as early as 1963, and taken over by the label when they recruited Tim to their roster. A few of the items – “Ain’t Gonna Do Without” and “Smuggling Man” had already been plundered from these tapes and slipped onto

‘1’ without Hardin’s consent. The former is a retread of “Long Tall Shorty” personalised by the opening lines ‘they call me long tall Timmy’. Now “Airmobile” is a Chuck Berry-styled number, taken uncharacteristically up-tempo. The inclusion of “Bo Diddley” sees a second nod in the same direction, while “Whiskey, Whiskey” is an impromptu thing made up in the studio. The album’s inclusion of “House Of The Rising Sun” and “Danville Dame” is also something of an oddity, as versions of these songs were already available on the Atlantic-vintage set

‘This Is Tim Hardin’. The musicians on

‘4’ are Hardin’s back-up from his Night Owl dates – Felix Pappalardi on bass, Sticks Eglin on drums, Bill Chuff on piano, and John Sebastian on rhythm guitar and harmonica. The latter appearing just prior to forming Lovin Spoonful.

SIMPLE SONGS OF FREEDOM

If 1968 had proved to be a confusing year, then 1969 starts out as though it might go some way towards providing an artistic vindication. But there are continuities too. The sleeve of

‘2’ shows Tim gazing moodily out of a window. Behind him stands his pregnant wife, while the storyline of the conman-thief “Lady Came From Baltimore” reveals that ‘the lady’s name was Susan Moore.’ The first album for CBS is the extended song-cycle

‘Suite For Susan Moore And Damion: We Are One, One, All Is One’. An idyll to domesticity and married love, it proved an ambitious, if occasionally unwieldy project, ‘so laid-back’ according to

‘Melody Maker’ that ‘it barely exists.’ But what it lacks in the directness and melodic simplicity of

‘1’ and

‘2’ it goes some small way towards compensating through its inclusion of poetry eulogising his love for his new child and actress wife (she was featured in the US daytime Soap

‘The Young Marrieds’).

Sessions took place in Nashville, and in Hardin’s own Woodstock house in New York state – ‘the most comprehensive studio in existence. It was a log-house, you could almost have called it a mansion. It wasn’t palatial, but it was very large, and was built of split logs (

‘Melody Maker’ 26 January 1974). The playing time is separated into four distinct suites or ‘Implications’, the closing track – “Susan”, a recital on which he’s joined by his wife, while “A Question Of Birth” is about the onset of parenthood and its attendant responsibilities, which had started out as a poem printed on the reverse of

‘Tim Hardin 2’. The sleeve of the ‘Susan Moore’ package is an impressionistic orange-yellow painting quite at odds to the sparse and direct understatement of his earlier work. Reception was mixed.

‘New Musical Express’ opines that ‘gone is the simplicity – and in its place, a cynical sneer at life.’ Later, ultimately even Tim himself professed a sense of dissatisfaction with the set. ‘Maybe it was too soon, or maybe I did not have the right musical aggregation?’

1969 ended ironically with Hardin enjoying his only American chart single – a Bobby Darin penned “Simple Song Of Freedom”! A now-rare collector’s item it spent two weeks at no.50 on the

‘Cashbox’ lists. In some ways the song is self-parody and, on a wider scale, a pastiche of the whole Folk-Protest movement, clear down to the pseudo-PF Sloan inclusion of an irritating girlie chorus and the down-home philosophising of ‘we the people here, don’t want a war’. Tim carries the sentiment with broken sincerity, and makes the song his own.

Hardin was ‘bedevilled by ill-health and bad advice’, and with the collapse of his marriage, things did not get better. The album

‘Bird On A Wire’ in July 1971, largely consists of Hardin’s versions of other people’s songs. “Andre Johray” is original and impressive, and even

‘Melody Maker’ concedes that on the anguished title cut ‘Tim puts more feeling and personal significance into the song than even (its writer, Leonard) Cohen could muster.’ Such praise hardly mitigates the conspicuous lack of new material. “Bird On A Wire” itself starts with just electric keyboard, but builds to a big production job with chorus – Tim pointedly personalising the lyrics from ‘like a worm on the hook’ to ‘like a man on the hook’. The rest of the tracks develop into areas of textural sophistication that seem at odds with Hardin’s Folky roots. “Soft Summer Breeze” is vaguely funky – jazzers Joe Zawinul, Miroslav Vitous, Ralph Turner and Glenn Moore adding fusion flexibility to the sound. Bobby Hebb’s “A Satisfied Mind” is pleasant if unexceptional while the plaintive “Moonshiner” with its subtle convolutions works quite well. But the reading of Ray Charles’ “Georgia On My Mind” is occasionally embarrassing.

With this release it becomes apparent that expectations for new Hardin work can no longer be pitched as high as

‘1’ and

‘2’, and that this has become the new norm, not merely a bad career-patch. The somewhat doomy sleeve photo pictures Hardin heavily bearded and slouch-hatted, he also appears anaemically pale and unhealthy.

He later claimed he had yet to receive royalties for any of the many covers of his earlier songs – while new versions continue to mine that same slim vein. Cliff Aungier and Joan Baez record “Lady Came From Baltimore”, “Misty Roses” came from Johnny Mathis and Cilla Black, William E Kimber and Scott Walker cut versions of “Black Sheep Boy” while Ian Matthews chooses “Tribute To Hank Williams”. Nico’s exquisite

‘Chelsea Girl’ (1967) had already used Hardin’s “Eulogy To Lenny Bruce”, an association that led to a raucous and poorly-reviewed jam when Tim joins her on-stage at the LA ‘Whisky A Go Go’ in late June 1979.

Later, Wilson Phillips platinum debut album (1990) includes their close-harmony rendition of “Reason To Believe”, following a live cover of the same song done a year earlier by Billy Bragg (on a free flexi for

‘Catalogue’ magazine). The material is often handled with respect, but none can match the cracked melancholia of Hardin’s original – as emphasised when Verve reissue the first two albums as a double set, while simultaneously farming out the material onto compilations. “Misty Roses” oddly occurs on an Island sampler called

‘Windy Bama Winds’ (ILPS 9096)!

At the same time Tim began playing live British dates – including one at Tupholme Manor Park near Lincoln (24 July 1971) down-bill of the Byrds, and one at the ‘Rainbow’ with the Steve Miller Band (4 March 1972).

‘Painted Head’ (1973) became Tim’s last set for CBS. It was recorded at the Apple studios in London with Peter Frampton playing guitar, and Hardin displaying a strange mix of styles from the flawed R&B of “You Can’t Judge A Book By The Cover”, to the raucous rootsiness of the dance-orientated single “Do The Do”. Tim was obviously drawn by a long-term affinity to such Blues forays, but while strong voices-for-hire are useful, the ability to write a song as startling as “If I Were A Carpenter” is unique.

It was followed by

‘Nine’ (1973) – his last ever studio album, produced by Jimmy Horowitz for the British Indie GM label. A set that seems to be a culmination of directions signalled across the previous years – a steady move away from the Folk-Poet image, which he’d always repudiated anyway. As early as a March 1972 interview he’d told Michael Watts that he considers himself a singer rather than a songwriter. The Jazz-Blues roots had mellowed out into a kind of White Funk with Tim treated more as the group vocalist than a solo artist with support musicians. It seems an almost willed destruction of his own sensitivity, of his own ‘fast-flying muse’. ‘I should have been a tasteful Tom Jones’ he once confided – in a monumental misjudgement of his own potential, to Folk journalist Colin Irwin. The approach is accentuated – on “Person To Person”, by the chorus voices of Lesley Duncan and Madelaine Bell. Then, as if to stress the Blues continuity in his work, he reworks Fred Neil’s “Blues On The Ceiling”, first featured on

‘This Is Tim Hardin’.

Frampton is again in evidence on

‘Nine’, working with a band consisting of Dave Thompson on piano, Peter Dennis on bass, Jim Gannon on guitar and drummer Mike Driscoll. Alongside six self-penned songs Hardin selects material from Oscar Brown Jrn, and James Taylor’s “Fire And Rain” – a song singularly suited to both his interpretation and experience. There are meandering love songs, but the accent is decidedly against the lyrical, as distinct from the musical content, what

‘Q’ magazine describes as ‘aimless and shambolic – as indeed is most of the messy backing, Al Kooperesque organ, showband strings, crooning girls and all’ (John Bauldie, February 1991). But “Shiloh Town” – the most powerful of the new songs, catches something of his earlier stripped-back fire, on a humorous note with ‘it’s so cold in Shiloh Town, the birds can’t hardly sing, pretty girls are gonna leave the town, they won’t be back till spring’ – equating girls to migratory birds, then conflating Shiloh’s Civil War legacy with a hint at Vietnam, ‘the war has been won, they come back home, but they’re the one’s that lost, I see a man and a woman alone, was it worth the cost?’

The sleeve shows him looking more relaxed, clean-shaven, seen through a soft haze of cigar smoke. But Hardin was – by then, living and working in a ‘drug and booze haze’ (Bauldie) from a London address. To promote

‘Nine’ he toured with a four-piece group co-headlining with fellow GM artist Lesley Duncan, a tour that marked his first appearances in two years, apart from a guest spot at the Reading Festival. Later, in December 1975, he joined German experimentalists Can on stage at Drury Lane for a largely chaotic number – announcing him under the alias ‘Deacon James’.

There was also talk of a career link-up with Tim Rose, the man responsible for the late-sixties cult single “Morning Dew”, whose own once-promising career was also bottoming. They played a joint concert at London’s City University (7 November 1974), and although a qualified success, for those who truly cared about Tim Hardin, it was difficult to accept that he’d never again write songs of the calibre of those early gems. And although those first songs were still very much in circulation, still commanding respect, there was little but silence to come.

Leonard Cohen may have written a novel called

‘Beautiful Losers’ (1966), but it was Tim Hardin who lived the title.

Snatches of his personal and artistic decline can be glimpsed in snapshot images from the following years. Briefly Justin de Villeneuve – former Twiggy manipulator, became Hardin’s manager, retrospecting those days in his autobiography

‘An Affectionate Punch’ (1986, Sidgwick and Jackson). Reviews of the book speak of ‘the squalid junkie antics of a dying Tim Hardin’ (

‘New Musical Express’, 23 August 1986). A similar picture of terminal addiction is caught with excruciating accuracy in the factional novel

‘Wonderland Avenue’ by Doors devotee and Rock PR ‘Wild Child’ Danny Sugerman (1989, Sidgwick and Jackson).

Then there’s the final album, appropriately called

‘The Homecoming Concert’ (1982), played live at the Community Center for the Performing Arts in Eugene, Oregon, and taped by former schoolfriend Phil Freeman. Hardin plays the concert solo. It’s sparse, naked, the cracks and bruises leaving his voice even more an instrument of desolate melancholy than it appeared doing the same songs on

‘Tim Hardin 3’. His twixt-song dialogues blur and wander disjointedly. It was 1980, the first time he’d played the town of his birth, and the last time he’d perform anywhere. There’s resignation in the inevitability of the song selection, drawing heavily from the first two albums, but a pride in the obvious strength of that material which he invests with compellingly stark dignity.

The opening number is “Black Sheep Boy”. The first line ‘here I am back home again, I’m here to rest…’

TIM HARDIN: REASONS TO BELIEVE

July 1966 – ‘

TIM HARDIN 1’ (Verve SVLP/VLP 5018, Verve Forecast FT/FTS 3004) with side one: ‘Don’t Make Promises’, ‘Green Rocky Road’, ‘Smugglin Man’, ‘How Long’, ‘While You’re On Your Way’, ‘It’ll Never Happen Again’. Side two: ‘Reason To Believe’, ‘Never Too Far’, ‘Part Of The Wind’, ‘Ain’t Gonna Do Without’, ‘Misty Roses’, ‘Hang Onto A Dream’. Producer: Erik Jacobsen

1966 – ‘Don’t Make Promises’ c/w ‘Smugglin Man’ (Verve Forecast VS 1516)

January 1967 – ‘Hang Onto A Dream’ c/w ‘Reason To Believe’ (Verve VS 1504) UK no.50

March 1967 – ‘Black Sheep Boy’ c/w ‘Misty Roses’ (USA, Verve Folkways KF 5048)

April 1967 – ‘

TIM HARDIN 2’ (Verve VLP 6002, Verve Forecast FT/FTS 3022) with side one: ‘If I Were A Carpenter’, ‘Red Balloon’, ‘Black Sheep Boy’, ‘The Lady Came From Baltimore’, ‘Baby Close Its Eyes’. Side two: ‘You Upset The Grace Of Living When You Lie’, ‘Speak Like A Child’, ‘See Where You Are And Get Out’, ‘It’s Hard To Believe In Love For Long’, ‘Tribute To Hank Williams’. Original LP release has back-cover Tim Hardin poem ‘A Question Of Birth’. Producer: Charles Koppelman and Don Rubin

June 1967 – ‘Tribute To Hank Williams’ c/w ‘You Upset The Grace Of Living’ (Verve Forecast KF 5059)

September 1967 – ‘

THIS IS TIM HARDIN’ (Atlantic 587082, ATCO 33-210) demos from 1963-1964 with side one: ‘I Can’t Slow Down’ (Tim Hardin), ‘Blues On The Ceiling’ (Fred Neil), ‘Stagger Lee’ (Trad), ‘(I’m Your) Hoochie Coochie Man’ (Willie Dixon), ‘I’ve Been Working On The Railroad’ (Trad). Side two: ‘House Of The Rising Sun’ (Trad), ‘Fast Freight’ (Hardin with Terry Gilkyson), ‘Cocaine Bill’ (Trad), ‘You Got To Have More Than One Woman’ (Hardin), ‘Danville Dame’ (Hardin with Steve Weber). Producer: Daniel N Flickinger. Reissued Edsel ED 309

November 1967 – ‘Lady Came From Baltimore’ c/w ‘Black Sheep Boy’ (Verve Forecast VS 1511)

November 1968 – ‘

TIM HARDIN 3: LIVE IN CONCERT’ (Verve VLP 6010, Verve Forecast FTS 3049) with ‘Lady Came From Baltimore’, ‘Reason To Believe’, ‘You Upset The Grace Of Living’, ‘Misty Roses’, ‘Black Sheep Boy’, ‘Lenny’s Tune’, ‘Don’t Make Promises’, ‘Danville Dame’, ‘If I Were A Carpenter’, ‘Red Balloon’, ‘Tribute To Hank Williams’, ‘Smugglin Man’. Producer: Gary Klein. Reissued with bonus tracks ‘Turn The Page’, ‘If I Knew’, ‘Last Sweet Moment’ and ‘First Love Song’

February 1969 – ‘

TIM HARDIN 4’ (Verve SVL 6016, Verve Forecast FTS 3064) recordings from May 1964, with ‘Airmobile’, ‘Whiskey Whiskey’, ‘Seventh Son’ (Willie Dixon), ‘How Long’, ‘Danville Dame’, ‘Ain’t Gonna Do Without: Parts 1 and 2’, ‘House Of The Rising Sun’ (Trad), ‘Bo Diddley’ (Bo Diddley), ‘I Can’t Slow Down’, ‘Hello Baby’. Producer: Erik Jacobsen

April 1969 – ‘

SUITE FOR SUSAN MOORE AND DAMION: WE ARE ONE, ONE, ALL IN ONE’ (CBS 63571, Columbia CS 9787) with side one: Implication 1 ‘First Love Song’, ‘Everything Good Became More True’, Implication 2 ‘Question Of Birth’, ‘Once Touched By Flame’, ‘Last Sweet Moments’. Side two: Implication 3 ‘Magician’, ‘Loneliness She Knows’, End Of Implication ‘The Country I’m Living In’, ‘One, One, The Perfect Sum’, ‘Susan’. Producer: Gary Klein

September 1969 – ‘Simple Song Of Freedom’ c/w ‘Question Of Birth’ (Columbia 4-44920) US no.50

July 1971 – ‘

BIRD ON A WIRE’ (CBS 64335, Columbia CK-30551) with side one: ‘Bird On The Wire’ (Cohen), ‘Moonshiner’ (Trad), ‘Southern Butterfly’, ‘A Satisfied Mind’ (Joe Hayes and Jack Rhodes), ‘Soft Summer Breeze’. Side two: ‘Hoboin’ (John Lee Hooker), ‘Georgia On My Mind’ (Hoagy Carmichael), ‘Andre Johray’, ‘If I Knew’, ‘Love Hymn’. Producer: Ed Freeman

January 1973 – ‘Do The Do’ c/w ‘Sweet Lady’ (CBS S 1016)

February 1973 – ‘

PAINTED HEAD’ (CBS 65209, Columbia CK-31764) with side one: ‘You Can’t Judge A Book By The Cover’ (Willie Dixon), ‘Midnight Caller’ (Pete Ham), ‘Yankee Lady’ (Jesse Winchester), ‘Lonesome Valley’ (Trad), ‘Sweet Lady’ (Dino-Sembello). Side two: ‘Do the Do’ (Willie Dixon), ‘Perfection’ (Pete Ham), ‘Till We Meet Again’ (Neil Sheppard), ‘I’ll Be Home’ (Randy Newman), ‘Nobody Knows You When You’re Down And Out’ (Tony Cox). Producer: Tony Meehan

November 1973 – ‘

NINE’ (GM GLM 1004, Antilles AN-7023) with side one: ‘Shiloh Town’, ‘Never Too Far’, ‘Rags And Old Iron’ (Oscar Brown-Norman Curtis), ‘Look Our Love Over’, ‘Person To Person’ (Hardin with Andy Brown). Side two: ‘Darling Girl’ (d’Albuquerque), ‘Blues On The Ceiling’, ‘Is There No Rest For The Weary’ (Troiano), ‘Fire And Rain’ (James Taylor), ‘While You’re On Your Way’ plus 1994 bonus track ‘Judge And Jury’ (1973 UK-only single). Producer: Jimmy Horowitz. Reissued Marquee Classic MQCLP 003

1981 – ‘

UNFORGIVEN’ (San Francisco Sound SFS 10810), uncompleted studio recordings and home cassette demos from 1980, side one: ‘Unforgiven’, ‘Luna Cariba’, ‘Mercy Wind’, ‘If I Were Still With You’. Side two: ‘Judge And Jury’, ‘Partly Yours’, ‘Sweet Feeling’, ‘Secret’ with Nicky Hopkins (Piano), Ricky Fataar (drums), Johnny Lee (guitar) and producers Don and Caroline Rubin

April 1981– ‘

THE HOMECOMING CONCERT’ (Kamera/ Line LLP 5124 AS, Line Germany LICD 9.00040) recorded 17 January 1980 with ‘Black Sheep Boy’, ‘Misty Roses’, ‘Reason To Believe’, ‘Lady Came From Baltimore’, ‘Old Blue Jeans’, ‘Hang Onto A Dream’, ‘If I Were A Carpenter’, ‘Tribute To Hank Williams’, ‘Smugglin Man’, ‘Speak Like A Child’, ‘Red Balloon’, ‘Amen’. Producer: Phil Freeman

Compilations:

September 1969 – ‘

THE BEST OF TIM HARDIN’ (MGM 2317 003/ SVLP 6019, Verve Forecast FTS 3078) with side one: ‘Don’t Make Promises’, ‘It’ll Never Happen Again’, ‘Tribute To Hank Williams’, ‘Misty Roses’, ‘Hang Onto A Dream’. Side two: ‘If I Were A Carpenter’, ‘Reason To Believe’, ‘Black Sheep Boy’, ‘Red Balloon’, ‘Smugglin Man’, ‘Lady Came From Baltimore’

1981 – ‘

THE TIM HARDIN MEMORIAL ALBUM’ (Polydor PD-1-6333)

August 1974 – ‘

TIM HARDIN 1/ TIM HARDIN 2’ (Verve Double Album)

1981 – ‘

TIM HARDIN: THE SHOCK OF GRACE’ (CBS Columbia PC 37164) compilation compiled by Bruce Dickenson from the three CBS albums

1989 – ‘

TIM HARDIN: REASON TO BELIEVE’ (Polydor 833954) compilation compiled from ‘Tim Hardin 1’ and ‘Tim Hardin 2’

1990 – ‘

READING FESTIVAL 1973’ (Marquee MQCCD001, SEECD 343), live album with just two Hardin tracks, ‘Hang Onto A Dream’ and ‘Person To Person’, plus the Faces (‘Losing You’, last ever Rod & Faces appearances), Lesley Duncan (‘Earth Mother’), Rory Gallagher (‘Hands Off’), Strider, Status Quo

Album Review of:

‘REASON TO BELIEVE:

THE SONGS OF TIM HARDIN’

by VARIOUS ARTISTS

(Fulltime Hobby FTH100CD)

Tim Hardin could do simple. And that’s difficult. Lots of folk can do complex. That’s more obvious. It was Tim’s gift of simplicity that makes his songs ideal for interpretation. As Barney Hoskyns’ excellent insert-notes point out, Hardin had ‘the shock of grace’. And everyone has already plundered that grace. From Bobby Darin and the Small Faces, through to Johnny Mathis and the appalling Rod Stewart. Yet these thirteen carefully thought-through new covers both choose less obvious titles from the back-catalogue, and add some unexpected soundscapes, from regular acoustic indie through to otherwise unfamiliar settings. Mark Lanegan’s “Red Balloon” doesn’t mess with the original and stays close to the blueprint, while Snorri Helgason and Alela Diane take both “Misty Roses” and “Hang Onto A Dream” pretty-much straight revealing the song’s clean purity. Unlike the Smoke Fairies’ dense massive attack on “If I Were A Carpenter” and the piercingly incisive Hannah Peel on the Lenny Bruce tribute (‘why after every last shot, was there always another’), or the Magentic North’s reinterpretation of “It’s Hard To Believe” taken in a way that drives you back to recheck the Hardin version. Elsewhere the Sand Band’s dobro-keening “Reason To Believe”, and “Shiloh Town” in the hands of Gavin Clark becomes a country-strum rising into anthemic heights. Most radical revision is (Sam Gender’s) Diagrams bleeping-reworking of “Part Of The Wind” and Pinkunoizu’s haunted electro-World “I Can’t Slow Down”. While the ensemble close-harmony Phoenix Foundation’s “Don’t Make Promises” would be a hit single in some kinder cleverer alternate reality. Thirteen new Reasons To Believe. A new dream to hang onto.

Published in:

‘R2: ROCK ‘N’ REEL Vol.2 Issue.39 May/June’

(UK – May 2013)