MUNGO JERRY:

AFTER THE

SUMMERTIME IS OVER

It’s strange that this starts out with a ‘find your own space’ TV-ad for Linkedin. The concept of work has changed, so where do we fit in? Apparently, in vibrant street communities where a healthy diversity of people meet and debate in an open and accepting way. And the thumping theme that choregraphs it all – ‘Oh I’ve been thinking ‘bout my life, what’s been wrong and what’s been right, some say that some say this, some say no, some say yes.’ That’s Mungo Jerry. Always a community band. Although maybe this twenty-first-century commercial tie-in wasn’t quite what they had in mind at the time of its release. “Alright Alright Alright” – their July 1973 no.3 hit record, was not the first time they’d soundtracked a TV commercial. Although mostly the sponsors had gone for the biggest most recognisable hit – “In The Summertime”. Nevertheless, each slight enhanced visibility afforded by such tacky sponsorship ventures, tweaks the back catalogue yet again.

“In The Summertime” itself was the kind of hit song that a band is both fortunate, and unfortunate to enjoy.

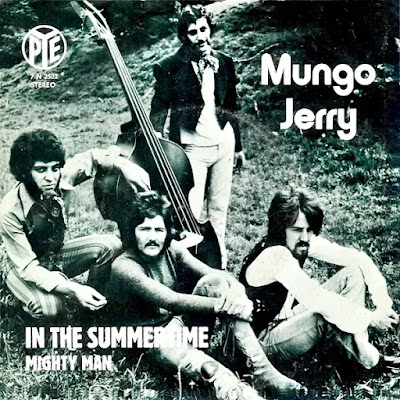

Mungo Jerry were a constantly reshuffled line-up of Skiffle revivalists, dominated by the personality of big-Afro-haired and luxuriantly side-whiskered lead singer-writer Ray Dorset, born in 1946 in Ashford, Kent. He’d been performing since he was just fourteen. Originally named Good Earth – Dorset (guitar, voice & ‘stomper’), Colin Earl (piano), Paul King (banjo & jug) & Mike Cole (string bass), were a popular live travelling band with a high-energy blend of Rockabilly, Blues and Skiffle. Ray had paid his song-writing dues when the group played back-up to Ska-artist Jackie Edwards (who co-wrote hits with Steve Winwood for the Spencer Davis Group). Ray claims he sketched out the “In The Summertime” riff one night in 1969 on a second-hand Fender Stratocaster, jotting the lyrics the following morning during his day-job as a Lab Researcher at Timex.

There was a new-decade buzz in the air. The old sixties gods were stumbling or crumbling. The seventies would inherit their underground progressive vibe and take it into yet more amazing highs. Early in 1970 Good Earth cut several tracks at the Pye studios with producer Barry Murray – who also functioned as their first manager. The label was impressed. By serendipitous good fortune, it happened just as the group were a hit at the June 1970 Hollywood Festival, pitched outside Newcastle. Despite a bill that listed Traffic, Free, Black Sabbath and the Grateful Dead, their Saturday night set created such a spontaneous buzz they were promptly added to the Sunday night bill too.

They were crowd-pleasers. The convention of virtuoso guitar soloing had started out with Eric Clapton, Jimi Hendrix, Steve Winwood and Jerry Garcia, musicians of innovative skills who knew how to extemporise and had the dexterity to justify doing it. When the solo fell into lesser-gifted hands and became a mere expectation, a degree of tedium sets in. With the festival stage dominated by band after band playing leaden extended po-faced improvisations, the unpretentious appearance of Mungo Jerry’s brand of organic up-tempo good-time music was greeted with ecstatic dance-along enthusiasm. No drums, just Ray stomping his boot to establish the rhythm, a grassroots reversion to the natural energies of raucous stamping, kazoo-tooting, honking jug-band Folk-Blues boogies at their most gleeful. They were not Rock gods, they were one with the audience, but with just a mischievous glint, ‘we’re no threat, people, we’re not dirty, we’re not mean, we love everybody, but we do as we please…’

Still known as Good Earth, until the very last moment, a hasty group-meeting resulted in a name-switch to that of one of the mischievous ‘Mungojerrie & Rumpleteazer’ cats from TS Eliot’s 1939 ‘Old Possum’s Book Of Practical Cats’ verses. But ‘mungo’ was also a rag-trade term once used to describe scavenged cloth made from recycled woven or felted material. While simultaneously, also by serendipitous good fortune, Pye Records were in the process of launching a new subsidiary aimed at the counterculture audience. And ventured a new technological innovation – which could be read as ‘gimmick’, in the form of the maxi-single.

Since the introduction of the first vinyl 45rpm single, the high-profile plug-track A-side was matched to its flipside. A format that worked really well when two strong numbers were twinned, with classic pairings such as Elvis’ “His Latest Flame” c/w “Little Sister”, Ricky Nelson’s “Hello Mary Lou” c/w “Travelin’ Man”, Cliff Richard’s “The Next Time” c/w “Batchelor Boy” or the Beatles “We Can Work It Out” c/w “Day Tripper”, but it could also consist of a throwaway filler. Royalties were split down the middle, so a hasty number cobbled together by the producer or astute manager would generate as much revenue as the hit side. Phil Spector adopted the technique of focusing all radio play on the designated A-side by placing disposable instrumentals on the B-side. Brian Wilson did pretty-much the same by taking the epic “Heroes And Villains” and sticking the 1:07-minute “You’re Welcome” on the flip, a simple repetition of the lyric ‘you’re welcome to come.’ During later decades the B-side became merely a ‘remix’ of the A-side, often an ‘instrumental version’ which consists of the plug-track with the vocal omitted!

Dawn’s promotional idea was to reverse that mentality and carry two tracks on the B-side… making it a good-value Maxi-Single. So the “In The Summertime” package also includes Ray’s bragging kazoo-driven “Mighty Man” plus their down-dirty harmonica-led cover of Woody Guthrie’s “Dust Pneumonia Blues”. The contagious hit-track uses breathy interjections of vocal rhythm effects, with just a lyric hint of Hendrix, ‘you can stretch right up and touch the sky’ but in summertime, when the weather is hot, ‘you got women, you got women on your mind.’ There’s a teasing nudge of class distinction between ‘if her daddy’s rich, take her out for a meal, if her daddy’s poor, just do what you feel,’ and a bridging motorcycle sound (actually sampled live from the studio engineer’s Triumph sports car!) placed at the false ending. Carried on high-rotation radio-play, accelerated by press coverage of their Hollywood success, the massive-selling “In The Summertime” (Dawn DNX 2502) debuted at no.13. It rapidly reached no.1, 13 June 1970, where it stayed put, hogging the top spot for seven weeks. Ray had to wangle time off work for a ‘Top Of The Pops’ debut performance, after which he quit the nine-to-five for music. The song went on to top charts around the world, peaking at no.3 on the American Billboard Hot 100.

Becoming known – on such a spectacular level, for just one catchy song, is a gift delivered in a tainted chalice. Singles, in general, were not considered as serious creative entities without the support of an attendant album. With their own multi-million-selling debut single Procol Harum had discovered that “A Whiter Shade Of Pale” set an impossible benchmark, and that no matter how good subsequent work was – and there were some wonderful albums, they would always be known for that one Summer Of Love classic. “In The Summertime” was a cross-over hit that everyone knew, sung by all and sundry from schoolkids to the morning milk-delivery man. Everything that followed would be unfairly measured against its success.

The album ‘Mungo Jerry’ (August 1970, Dawn DNLS 3008) was wrong-footed from the start, it was even issued on Pye’s other label ‘Janus Records’. There were five original songs by Ray. Three written by Paul King. “Daddies Brew” credited to Colin Earl, and “Mother *!*!*! Boogie” listed as a group composition. There were also strong covers of one-man-band Jesse Fuller’s “San Francisco Bay Blues” and “Baby Let’s Play House” – a song written and first recorded by Arthur Gunter but a 1955 Rockabilly hit for Elvis Presley. For some foreign editions “In The Summertime” was hastily tacked onto the album as an afterthought. While the music scribes of ‘New Musical Express’ and ‘Melody Maker’ were extolling the virtues of the latest Led Zeppelin or Deep Purple twelve-inchers, they tended not to apply the same level of critical attention to Mungo Jerry. Rock music was intensely serious. Mungo Jerry were fun, and fun, even when it was grounded in genuine Folk-Blues roots, did not figure on their radar.

Yet there were even opportunistic spin-offs, The Mixtures issued an Australian cover of “In The Summertime” which topped the chart there, while “Seaside Shuffle” by Terry Dactyl & The Dinosaurs (UK5), was an early fun project for Jona Lewie which pinched the zob-stick percussion and seaside effects with an unmistakably catchy “In The Summertime” vibe which took it into the UK charts 15 July 1972, and all the way up to no.2. Later there a Rap-reggae revival of “In The Summertime” by Shaggy, which did very nicely, while the song’s lyric ‘have a drink, have a drive, go out and see what you can find’ led to its use in an anti-drink driving TV campaign.

There was a time-lag between the first two Mungo Jerry singles. They took the collective decision to delay unleashing the follow-up until the massive international sales of “In The Summertime” died down. “Baby Jump” had been written during the 1968 overlap into 1969, and was already a concert favourite under an alternate title. When the band agreed this was to be the vital second single Dorset re-drafted the lyric and devised the new title – “Baby Jump” (Dawn DNX 2505). Recorded initially at the sixteen-track Pye studio, they weren’t happy with the result, so they re-recorded it at the same eight-track studio they’d used for “In The Summertime”. To confront head-on the accusations of lightness, this was a full-on heavy assault with Beefheartian yelps and a lyric both cleverly lustful and literate, ‘I dream that she was Lady Chatterley, ’n’ I was the game keeper, I dream that I was Da Vinci and she was the Mona Lisa, I dream that I was Humbert and she was Lolita.’ At a time when DH Lawrence and Nabokov were both hot topics. Sting would later flaunt his intellectual credentials by referencing ‘just like the old man in that book by Nabokov’ on the Police hit “Don’t Stand So Close To Me” – but Ray Dorset had got in there first! The thumping snarling beat false-closes, then roars back for a repeat verse. When it rose to no.1 – for two weeks, from 6 March 1971, Mungo Jerry became one of a select few acts whose first two releases both topped the charts.

Mungo Jerry were always the instant party. Where other bands were striving for credibility, they were grounded in the Rent Party ethic, yet drew from an equally deep reservoir of traditional music. A third single, the catchy “Lady Rose” (Dawn DNX 2510) with a sequence of swapped-vocal repetitions in the wind-down, peaked at no.5. It might have gone higher but its upward surge was arrested when a moral panic ensued over its inclusion of “Have A Whiff On Me”. Lonnie Donegan had scored a no.11 1961 hit by craftily reshaping the same song into a more acceptable “Have A Drink On Me”, but Mungo Jerry revert back to Woodie Guthrie’s original words about ‘Cocaine Sue’ and ‘who wants friends when you can have snow?’ The track was hastily switched to one from the album (“She Rowed”), but by then the momentum was lost.

That second album also fell foul of moral disapproval. The risqué nudge-nudge wink-wink title ‘Electronically Tested’ (April 1971, Dawn DNLS 3020) was a claim prominently displayed on each packet of Durex condoms. It was a degree of playful cheek that did not escape the diligent guardians of the nation’s standards of decency. Leading to all manner of tut-tut-tutting radio bans. Despite a strong track-listing, with a high hits quotient – including both group no.1’s, the set is made up of all Ray Dorset originals but for a lengthy cover of Willie Dixon’s “I Just Wanna Make Love To You”, known predominantly through its Etta James interpretation, but which stands up well to comparison with the Rolling Stones own version on their 1964 debut LP. A contrasting gear was supplied by the slower “Coming Back To You When The Time Comes”, while a later expanded CD edition adds Paul King’s hoedown “The Man Behind The Piano” (one of the “Baby Jump” B-sides) with twanging jaw-harp break.

There’s some wonderfully atmospheric video footage of the Weeley Festival held just outside Clacton over the 1971 August Bank Holiday weekend – later chronicled as ‘The Great British Woodstock’, in which the Faces and T Rex play on a bill with Edgar Broughton Band and the Pink Fairies who simply turn up and play for free. Quintessence might have been pushing the boundaries of East-West world music, Colosseum were extending and extemporising into Jazz-Rock fusion. But Mungo Jerry were there to party. Arriving in the ‘Fun Bus’ they were scheduled for the Friday noon slot, augmented for their set by Joe Rush on washboard. The video is soundtracked by an energetic version of the next hit – “You Don’t Have To Be In The Army To Fight In The War” (Dawn DNX 2513), a clever rootsy song using war as a metaphor for the rigours of outsider misfit living. He’s thrown out the door by his girlfriend’s parents because his hair’s too long and ‘you’re not their kind of bloke,’ he’s fired from his job ‘because your punctuality’s poor,’ then he’s barred from the hotel ‘because your shirt ain’t white.’ The song closes with ‘you’re tired and you’re hungry and you cannot walk no more… ain’t no money, ain’t no woman, ain’t no roof above your head, so you lay down in the park and you wish that you were dead, the fuzz says you are trespassing and kicks you in the jaw.’ It’s a full picaresque underground comic-strip complete with the ‘fuzz’ (police) terminology, and although the single enters the charts at no.48 in September 1971 it peaks at no higher than no.13 the following month. Although to this listener – alongside “Baby Jump”, it’s one of their strongest sides.

Following an Australian tour, there’s a dispute over whether or not they should recruit a conventional drummer to augment Ray’s signature footstomp percussion. Paul King had always provided the counterbalance to Ray’s more jaunty energies. When the dispute resulted in he and Colin Earl quitting, it had the effect of weakening the interactive cohesion of the Good Earth personnel, and focused the group’s core more tightly around Ray (although Colin would later return). The cover-art for ‘Electronically Tested’ shows the full group playing uproariously together on a festival stage, but by the time of the cartoon-art for ‘Boot Power’ (October 1972, Dawn DNLS 3041) Ray stands prominently in the foreground while the other members are grouped around a table in the background.

Yet the slower crawl of the swamp-Rock “Open Up” (Dawn DNX 2514) gets no higher than no.21. Followed by the smooth summery-harmonies and phased guitars of “My Girl And Me” (Dawn DNX 2515) which fails to chart at all. Although this proved to be a temporary set-back. Ray Dorset was back in time for a last hurrah hit with “Alright Alright Alright” (Dawn DNS 1037). This was not only the first Mungo Jerry single to be issued in standard 45rpm two-track format, but it was also a version of a French hit “Et Moi, Et Moi, Et Moi” originally done by Jacques Dutronc (written with Jacques Lanzmann) with English lyrics provided by Ray Dorset. Retaining all the shambling energies that hallmark Mungo Jerry’s best, after entering the chart at no.23 (14 July 1973) it leaps to no.5, to peak at no.3 beneath Gary Glitter’s “Leader Of The Gang (I Am)” and Peters & Lee’s anodyne “Welcome Home”! A huge high-energy hit, it would return in 2022 as a TV-ad! But by then the brief Mungo Jerry chart summertime was drawing to a close. The echoey Rock ‘n’ Roll sound of “Wild Love” (Dawn DNS 1051) had less impact, despite power-lyrics ‘she walks like a tiger, sounds like a lion, roars like a wildcat, hits you like thunder, grabs you like lightning, truly like morrow, she is like Monroe...’

The hits and visibility grind to an eventual halt around summertime 1974 with the choogling “Long Legged Woman Dressed In Black” (Dawn DNS 1061) with drumkit, and a lascivious catchily repetitive ‘everytime I make a move, she tells me no.’ By this time the line-up was Ray Dorset (guitar, vocals), Dick Middleton (guitar), Bob Daisley (Australian born bass-player, later with Ozzy Osbourne), Ian Milne (keyboards) and Dave Bidwell (drums). Briefly they were billed as Ray Dorset & Mungo Jerry. After which Dorset remained a very active part of the music scene. When critics attack the group’s music for its occasional sameness he had released a solo album – ‘Cold Blue Excursion’ (1972, Dawn DNLS 3033), which experiments with forays into a variety of styles from Gospel to one track using a Trad Jazz Band, with dubious success.

Always a big seller across Europe, Ray retained that popularity and scored a Euro-hit with “It’s A Secret” (Polydor 2058 713), which also gave him a South African no.1, although most of the familiar Mungo Jerry trappings had been discarded along the way. Then he wrote Kelly Marie’s breakthrough hit. Strip away the tacky Disco trappings of her “Feels Like I’m In Love” and it’s recognisably a Ray Dorset composition. Although he’d written it with the intention of sending the demo to Elvis Presley’s management, the King’s death meant the song was relegated to the B-side of a French Mungo Jerry single. Before it was spotted by Elliott Cowen of Red Bus Music as the perfect vehicle to launch the Scottish-born singer’s career in the UK. It was no.1 for two weeks from 13 September 1980. Ray also wrote the Channel 4 TV theme tune to the Gary Olsen comedy-drama series ‘Prospects’ (1986), and Paul Daniel’s ‘Wizbit’ BBC children’s fantasy show (1986-1988), as well as for the official Wigan football team anthem.

While each slight enhanced visibility afforded by tacky commercial ventures helped tweak the back catalogue yet again…

6 June 1970 – “In The Summertime” + “Mighty Man” c/w “Dust Pneumonia Blues” (33-&-a-third rpm, Dawn DNX 2502) no.1, in the charts for 20 weeks.

25 July 1970 – “In The Summertime” (Janus 125) USA, no.3, in the charts for 11 weeks.

8 August 1970 – ‘MUNGO JERRY’ LP (Dawn DNLS 3008) no.13, in the charts for 6 weeks. With side one (1) ‘Baby Let’s Play House’ written by Arthur Gunter, 2:32, (2) ‘Johnny B Badde’, Ray Dorset, 3:00 (3) ‘San Francisco Bay Blues’, Jesse Fuller, 3:38, (4) ‘Sad Eye Joe’, Paul King, 2:50, (5) ‘Maggie, Dorset, 4:10, (6) ‘Peace In The Country’, Dorset, 3:05. Side two (1) ‘See Me’, Dorset, 3:37, (2) ‘Movin’ On’, King, 4:14, (3) ‘My Friend’, Dorset, 2:36, (4) ‘Mother *!*!*! Boogie’, Earl-Cole-King-Dorset, 2:48, (5) ‘Tramp’, King, 5:05, (6) ‘Daddies Brew’, Colin Earl, 3:40.

6 February 1971 – “Baby Jump” + “The Man Behind The Piano” (King) c/w 9:50-minute ‘Live From Hollywood’ medley with excerpt from “Maggie”, “Midnight Special” & “Mighty Man” (33-&-a-third rpm, Dawn DNX 2505) no.1, in the charts for 13 weeks.

10 April 1971 – ‘ELECTRONICALLY TESTED’ LP (Dawn DNLS 3020) no.14, in the charts for 8 weeks. With Side one: ‘She Rowed’, Dorset, 3:15, (2) ‘I Just Wanna Make Love To You’, Willie Dixon, 9:01, (3) ‘In The Summertime’, Dorset, 3:30, (4) ‘Somebody Stole My Wife’, Dorset, 2:53. Side two (1) ‘Baby Jump’, Dorset, 4:09, (2) ‘Follow Me Down’, Dorset, 3:17, (3) ‘Memoirs Of A Stockbroker’, features Roger Earl on drums and Tony Bissiker’s recorder, Dorset, 4:00, (4) ‘You Better Leave That Whisky Alone’, Dorset, 3:55, (5) ‘Coming Back To You When The Time Comes’, Dorset, 3:38.

29 May 1971 – “Lady Rose” + “Little Louis” (Paul King) c/w “Milkcow Blues” + “Have A Whiff On Me” (substituted by “She Rowed”) (33-&-a-third rpm, Dawn DNX 2510) no.5, in the charts for 12 weeks.

18 September 1971 – “You Don’t Have To Be In The Army To Fight In The War” + “The Sun Is Shining” c/w “We Shall Be Free” + “O’Reilly” (33-&-a-third rpm Dawn DNX 2513) no.13, in the charts for 8 weeks.

October 1971 – ‘YOU DON’T HAVE TO BE IN THE ARMY’ LP, Music-cassette, 8-track (Dawn DNLS 3028) with Side one: (1) ‘You Don’t Have To Be In The Army To Fight In The War’, Dorset, 3:27, (2) ‘Ella Speed’, Dorset-trad, 3:12, (3) ‘Pidgeon Stew’, Dorset, 2:52, (4) ‘Take Me Back’, Dorset-trad, 3:28, (5) ‘Give Me Love’, Dorset, 3:50, (6) ‘Hey Rosalyn’, writer-&-vocals Paul King, 3:49. Side two: (1) ‘Northcote Arms’, Dorset, 3:17, (2) ‘There’s A Man Going Round Taking Names’, Dorset-trad, 3:09, (3) ‘Simple Things’, Dorset, 3:54, (4) ‘Keep Your Hands Off Her’, Dorset-trad, 2:49, (5) ‘On A Sunday’, Dorset, 3:19, (6) ‘That Old Dust Storm’, Guthrie, 3:31. With Ray Dorset (vocals, electric & six-string acoustic guitars, accordion, stomp), John Godfrey (bass guitar, electric piano), Colin Earl (piano), Paul King (vocals, banjo, twelve-& six-string acoustic guitar, jug), Joe Rush (washboard).

February 1972 – ‘COLD BLUE EXCURSION’ solo album as by Ray Dorset (Dawn DNLS 3033), with Side one: (1) ‘Got To Be Free’ 2:50, (2) ‘Cold Blue Excursion’ 4:09, (3) ‘With Me’ 3:15, (4) ‘Have Pity On Me’ with Joe Rush on washboard, John Godfrey (bass) and Colin Earl (backing vocals) 2:57, (5) ‘Time Is Now’ 3:30, (6) ‘Livin’ Ain’t Easy’ 3:30. Side two: (1) ‘Help Your Friends’ 4:11, (2) ‘I Need It’ 3:23, (3) ‘Because I Want You’ 4:17, (4) ‘Hightime’ 3:30, (5) ‘Maybe That’s The Way’ 3:04, (6) ‘Always On My Mind’ 2:53. Features Mike McNaught (piano), Dave Markee (electric bass), Mike Travis (drums), plus Sue & Sunny backing vocals. A quote by Woody Guthrie is used on the inner sleeve, ‘A song was just a song to me... in my own mind, a song is just a song...’ “Cold Blue Excursion” c/w “I Need It” (Dawn DNS 1018) spun off as a single.

22 April 1972 – “Open Up” + “Going Back Home” c/w “I Don’t Wanna Go Back To School” + “No Girl Reaction” (Dawn DNX 2514) no.21, in the charts for 8 weeks.

October 1972 – ‘BOOT POWER’ LP, Music-cassette, 8-track (Dawn DNLS 3041) with Side one: (1) ‘Open Up’, (2) ‘She’s Gone’, (3) ‘Looking’ For My Girl’, (4) ‘See You Again’, (5) ‘The Demon’. Side two: (1) My Girl And Me’, (2) ‘Sweet Mary Jane’, (3) ‘Lady Rose’, (4) ‘(Going Down The) Dusty Road’, (5) ‘Brand New Car’, (6) ‘Forty-six dOn’. With Ray Dorset (lead), Tim Reeves (drums), Jon Pope (keyboards), John Godfrey (bass), Barry Murray (producer).

3 November 1972 – “My Girl And Me” + “Summer’s Gone” c/w “Forty-Six And On” + “It’s A Goodie Boogie Woogie” (Dawn DNX 2515) did not chart.

7 July 1973 – “Alright Alright Alright” c/w “Little Miss Hipshake” (Dawn DNS 1037), no.3, in the charts for 12 weeks.

10 November 1973 – “Wild Love” c/w “Glad I’m A Rocker” (Dawn DNS 1051) no.32, in the charts for 5 weeks.

6 April 1974 – “Long Legged Woman Dressed In Black” c/w “Gonna Bop ‘Til I Drop” (Dawn DNS 1061) no.13, in the charts for 9 weeks.

September 1974 – ‘LONG LEGGED WOMAN’ LP, Music-cassette, 8-track (Dawn DNLS 3501) with Side one: (1) ‘Long Legged Woman Dressed In Black’, Ray Dorset, (2) ‘Glad I’m A Rocker’, Barry Murray, (3) ‘Gonna Bop ‘Til I Drop’, J Strange aka Barry Murray, (4) ‘Wild Love’, J Strange, (5) ‘O’Reilly’, Dorset-trad, (6) ‘The Sun Is Shining’, Jimmy Reed, (7) ‘Summer’s Gone’, Dorset. Side two (1) ‘Don’t Stop’, Dorset, (2) ‘Going Back Home’, Dorset, (3) ‘No Girl Reaction’, Dorset, (4) ‘Little Miss Hipshake’, B Murray, (5) ‘Milk Cow Blues’, Dorset-trad, (6) ‘I Don’t Wanna Go Back To School’, Dorset, (7) ‘Alright Alright Alright’, J Dutrone, J Lanzman, J Strange.

15 November 1974 – ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll With Mungo Jerry’ (EP, Dawn DNS1092) with “All Dressed Up And No Place To Go” + “Shake ‘Til I Break” c/w “Too Fast To Live And Too Young To Die”.

23 May 1975 – “In The Summertime” c/w “She Rowed” (seven-inch 45rpm single, Dawn DNS 1113).

4 July 1975 – “Can’t Get Over Loving You” c/w “Let’s Go” (Polydor 2058 603).

10 October 1975 – “Hello Nadine” c/w “Bottle Of Beer” (Polydor 2058 654).

February 1976 – ‘IMPALA SAGA’ LP, music-cassette (Polydor 2383 364) with Side one: (1) ‘Hello Nadine’ 3:22, (2) ‘Never Mind I’ve Still Got My Rock ‘n’ Roll’ 1:40, (3) ‘Ain’t Too Bad’ 3:15, (4) ‘Too Fast’ 2:30, (5) ‘It’s A Secret’ 3:14, (6) ‘Impala Saga’ 4:45. Side two: (1) ‘Bottle Of Beer’ 2:55, (2) ‘Get Down On Your Baby’ 7:53, (3) ‘Hit Me’ 5:21, (4) ‘Quiet Man’ 3:58, (5) ‘Never Mind I’ve Still Got My Rock ‘n’ Roll: Reprise’ 0:56. There was a German and French single “It’s A Secret” c/w “English Girls” (Polydor 2058 713), with a South African release as Polydor PS445.

30 July 1976 – “Don’t Let Go” c/w “Give Me Bop” (Polydor 2058 759).

1977 – “Sur Le Pont D’Avignon” c/w “Feels Like I’m In Love” (Polydor 2058 847), recorded in Dick James Studio with Alan Blakley of the Tremeloes, released in limited territories including Canada, Belgium and France.

15 April 1977 – “Heavy Foot Stomp” c/w “That’s My Baby” as Ray Dorset & Mungo Jerry (Polydor 2058 868).

May 1977 – ‘LOVIN’ IN THE ALLEYS FIGHTIN’ IN THE STREETS’ as Ray Dorset & Mungo Jerry, LP, music-cassette (Polydor 2383 435) with Ray Dorset (guitar, harmonica, vocals), Chris Warnes (bass), Pete Sullivan (drums), Colin Earl (keyboards).

10 June 1977 – ‘Mungo Rox’ EP as Ray Dorset & Mungo Jerry, with “All That A Woman Should Be” + “Dragster Queen” c/w “Get Down ON Your Baby” (Polydor 2230 103).

11 November 1977 – “We’re OK” c/w “Let’s Make It” (Polydor 2058 947).

March 1978 – ‘RAY DORSET & MUNGO JERRY’ as Ray Dorset & Mungo Jerry, LP, music-cassette (Polydor 2383 485).