RAYMOND F JONES:

MAN OF MANY WORLDS

Book Review of:

‘MAN OF TWO WORLDS’

by RAYMOND F JONES

(1944 as ‘Renaissance!’, 1951 Gnome Press,

as ‘Man Of Two Worlds’, Pyramid Books November 1963)

‘It is the Mystery of existence, the

Mystery of life that I would Seek out…’

This is a strange book, even by the standards of its time. There’s some unconscious humour which, almost comically absurd now, must surely have had the nudge-nudge factor even then. One of the ‘Mysteries’ that Ketan seeks to understand is, where do babies come from? New citizens emerge fully-formed, but sterile, from the ‘Temple of Birth’ with no memory of what came before. He has only hints and clues to base his enquiries on. Yet in this disturbingly odd conundrum he has unwitting companions within the Science Fiction continuum. In Arthur C Clarke’s ‘The City And The Stars’ (1956) Alvin is a ‘unique’ in far-future Diaspar, in which new citizens are created by the controlling central computer. Some time before Alvin, but in a similar way, Ketan comes to awareness in Kronweld, another closed community with a mighty computer-system called the Karildex. It is located on a world of two suns. Beyond the city in one direction lies the inhospitable Dark Land ‘where glowing firebursts lit the sky’ from the volcanic radioactive Fire Land. And in the other direction lies the impenetrable ‘Edge’, an ‘infinite curtain of blackness… a vast wall of negative existence that stretched from positive to negative infinity.’

Ketan is a Seeker who – like Alvin, is a discontented subversive, a member of the underground ‘Unregistered’ who secretly conspire to challenge the repressive secrecy of his society and penetrate its mysteries, demanding ‘the Mystery of the Temple of Birth, the Mystery of the great Edge, the Mystery of Fire Land. These things should not be closed to us.’ The Karildex constitutes a citywide internet making it ‘thus the law and the government’. So he breaks the seals on the master control board – what we’d now term ‘hacking into’ the ‘memory-circuits’ restricted to the First Group, searching for ‘the origin of human life’. He’s determined to provoke a confrontation with Teacher Daran that will precipitate a reprimand, and so enable a full public hearing, allowing him the opportunity of stating his case. But first, he has an unsettling encounter with an aged crazy-woman – ‘an old and withered husk’, who tells him of the Statists – agents of destruction infiltrating from beyond Kronweld, and of deaths to come. He realises that, ‘surging beneath the surface of Kronweld were strange, unknown forces of which he had never conceived. Forces that were merciless and swift.’

This is when the novel becomes decidedly odd. He’s pledged to ‘make companionship’ with the lovely Elta. In keeping with the scanty female garb of 1940’s Pulp Magazine cover-art, he finds ‘her slim brown body clad only in the universal fashion of brief, white harness that served necessary convenience and protection.’ But when Elta enters the female-only Temple, Ketan determines to follow her. So he uses a kind of ‘elastic moulding plastine’ to remould himself into female guise.

He then enters the temple by using a harpoon and grapple-line to scale up onto its flat-roof where he overpowers one of its Ladies, and orders her to undress, so that he can use her diaphanous gown to further his masquerade. ‘Out of your clothes, quickly now’ he demands, ‘I must exchange with you.’ When she refuses ‘he loosed one hand and tore the fastening loose at her throat and removed her robe.’ There’s no sexual element to this assault. He simply uses it to maintain the transgender identity for long enough to become involved in the bizarre politics of the enclosed order. There’s a coup. Aging Matra – the original crazy-woman of his earlier encounter, is murdered, replaced as matriarch by the ambitious Anetel. And he finds his answer. Infants emerge through a dimensional portal, opening out through the ‘Edge’. The fact that, throughout this lengthy sequence the reader has to hold in mind the unsettling image of him as a kind of remoulded Ladyboy tends to undermine its speculative gravity.

Surely all of this must have struck even its original readers as odd, when the novel was serialised in four parts as “Renaissance” in John W Campell’s ‘Astounding Science Fiction’? The first instalment appeared in the July 1944 issue, which not only also included Clifford D Simak’s “Huddling Place” – part of his ‘City’ story-cycle, but another Raymond F Jones story – “Utility”, published under the alias ‘David Anderson’. The serial continued through the August and September issues, to finish in the October issue with artwork by Paul Orban, alongside contributions from George O Smith, Lester del Rey and Isaac Asimov’s “Wedge” from his ‘Foundation’ cycle. The four episodes were first collected into book form in 1951 – as ‘Renaissance: A Science Fiction Novel Of Two Human Worlds’ by Gnome Press in an edition of 4,000 copies with cover-art by David Kyle graphically showing two colliding planets. Then the Pyramid paperback edition arrived in November 1963 as ‘Man Of Two Worlds’ – announcing it ‘a dazzling tale of adventure in the infinite future, a superhero’s quest for the forbidden, ultimate knowledge – the secret of all life!’

P Schuyler Miller describes the novel accurately as ‘a strangely moving book, overcoming its lack of characterisation and other traditional shortcomings by drive and sweep of imagination’ (in ‘Astounding SF’, December 1951). He’s correct in asserting that Ketan would be considered a narrow cipher within mainstream Lit-fiction, but that misses the point. His deep-cored restlessness is one acutely attuned to the mindset of its target readership. Like Arthur C Clarke’s Alvin, Ketan’s attitudes and stance perfectly snag the mood of petulant juvenile yearning, and the SF genre at that time was predominantly a male adolescent one. Ketan is impatient for change, frustrated by the tired complacency, the ‘slow dying senility’ and dull closed minds of those in power over him, just as the 1950’s ‘Rebel Without A Cause’ Beatniks would be, and in anticipation of the great upsurge of 1960’s counter-culture insurrection.

At Ketan’s interrogation by the Seekers Council in the House of Control, he is denounced for blasphemy as he defiantly argues his defence, proclaiming ‘I know enough to be sure that this is the only way progress can be made against superstition and blindness. You’ve got to smash through it and batter it down – or else live in its smothering encirclement.’ Yet Raymond F Jones makes for an odd subversive. He condemns his Statists as witch-burning Puritans. Yet he was born a Mormon (in Salt Lake City, Utah in 15 November 1915).

He first read HG Wells ‘War Of The Worlds’ when ‘Amazing Stories’ republished it in 1927, alongside the ‘wonderful aura’ of writers such as Ray Cummings, A Hyatt Verill, and Ralph Milne Farley who inspired him to write. He began his own SF career with short story “Test Of The Gods” in the ‘Astounding SF’ issue dated September 1941, but was soon contributing to other titles such as ‘Planet Stories’, ‘Super Science Stories’ and ‘Galaxy’ too. Some of his short stories were later collected into ‘The Non-Statistical Man’ (May 1964, Belmont), blurbed ‘one man’s mind spins a taut and eerie arc from the dark past into the distant future, and suddenly the world looks different!’, and ‘The Toymaker’ (1951, Fantasy Publishing) – which includes the pseudonymous “Utility” and “The Children’s Room”. The latter tale, about a protégé child, was adapted from ‘Fantastic Adventures’ (September 1947) into a TV episode of the ‘Tales Of Tomorrow’ (29 February 1952) anthology-series, while “Divided We Fall” – from ‘Amazing Stories’ (December 1950) became an episode of the British ABC-TV’s ‘Out Of This World’ (25 August 1962). Set in the year 2033, in grainy black-and-white, it portrays an omnipotent computer called Eddy which claims to have detected synthetic alien infiltrators called ‘Syns’, but scientist Dr Arthur Bailey (played by Bernard Horsfall) – fresh from two years on planet Cyprian, distrusts Eddy and is sceptical of the Syn’s existence. Jones also contributed to the ‘juvenile’ genre with the authorised spin-off from TV’s ‘Voyage To The Bottom Of The Sea’ (1956, Whitman Publishing), and his popular ‘Son Of The Stars’ novel-series featuring his interplanetary hero ‘Ron Barron’.

But it’s for the classic SF film ‘This Island Earth’ (Universal-International, 1955) that he’s best remembered. The story, in which visiting aliens recruit human scientists into their ‘Peace Engineers’ to assist their struggle against a stellar enemy, is based on a three-part Jones’ ‘Thrilling Wonder Stories’ serial, collected into a novel which Forrest J Ackerman’s literary agency placed with Shasta Books (1952). Selected for inclusion by two book clubs, it was published by Boardman in the UK and announced as ‘one of the truly memorable science fiction experiences of 1955. It combines a sense of social responsibility and thrilling action within the framework of a cosmic struggle to maintain a barrier against an incredible invasion. This book will appeal to everyone who has ever stopped on a starry night to gaze in wonder at the vastness of the universe, and to ponder the place in infinity of This Island Earth.’ Shatteringly well-filmed for its time, with eye-rippingly impressive technicolor visual extravagance, the screenplay is less than true to Jones’ plot.

Carl Meacham (Rex Reason) is contacted through ‘interocitor’ by white-haired Exeter (Jeff Morrow) – ‘Jorgasnovara’ in the novel, visualised by Virgil Finlay for its original magazine appearance. But these aliens are not intent on conquest, but on seeking help. The abducted scientists are taken ‘many galaxies away’ by saucer to an underground city on the devastated planet Metaluna, besieged by their Zahgonian aggressors. ‘Considerable money seems to have been spent on its production’ reports Forrest J Ackerman, ‘a reported $17,000 alone having been spent on the manufacture of the Mutant… a bulbous-brained beauty, head approximately four times normal size’ with ‘built-up shoulder muscles and arms twice normal length which terminate in ugly pincers’ (in ‘Nebula SF’ no.12, April 1955).

Metaluna is destroyed by targeted meteorite-strike, ‘intense heat is turning Metaluna into a radioactive sun. Temperature must be... thousands of degrees by now. A lifeless planet. And yet... yet still serving a useful purpose, I hope. Yes, a sun. Warming the surface of some other world. Giving light to those who may need it.’ Hokum, of course, but delivered with impressively straightfaced gravitas. Helping them escape back to Earth, a visionary Exeter explains ‘our universe is vast – full of wonders, while the ship has energy to fly, I will explore…’ Ludicrous, scientifically hopeless, yet speculating on which is the best science fiction film of all time, critics David Miller & Mark Gatiss decide that ‘for spectacle, mystery and the sheer joy of a journey to outer space, it has to be ‘This Island Earth’’ (in ‘They Came From Outer Space!’, Visual Imagination, 1996).

Meanwhile Ketan is discovered, and exiled through the ‘reaches of space and eternity’ to emerge from the other side of the portal into a new unfamiliar place. The Man of Two Worlds finds himself within the medieval forests of Earth, where people breed and sometimes die. It’s only now, commencing across the arid desert on a quest to find the Pinnacle of his earlier dream-vision with a new companion, the ill-kempt William Douglas, that he emerges from his female guise! And when he reaches the Pinnacle its long-dead interactive holo-guardians finally explain. Of course, Jones doesn’t call them ‘holograms’, but that’s what they are. Archimedes, Aristotle, Descartes, Michael Faraday, Newton and Einstein are all there, ‘men who tried to raise a world up to the stars’, alongside a kind of ‘Project Gutenberg’ archive of digital books.

With sombre Cold War prescience Ketan’s virtual hosts divulge that a thousand years ago global scientific warfare reduced civilisation to stone-age savagery, dividing society into science and anti-science factions. The planting of Crown World (Kronweld) in a parallel dimension was intended to create a sealed repository to preserve wisdom ‘before darkness closed in’, a ‘Foundation’ against centuries of barbarism, until it can re-emerge and impose an enlightened benevolent utopian rule upon the home world. There’s a kind of suspect elitism at work here as eugenic selection creams off the finest brains for Kronweld, leaving only the drudges to muddle through Earth’s gradual decline. Except that neither world has worked out as intended. Kronweld has degenerated into stultifying inertia, while the anti-science Statists plot across both worlds to frustrate its liberating destiny. Ketan requisitions the Pinnacle’s handy spaceship to take him to the ‘malignant intellectual hierarchy’ of the Statist city of Danfer, ruled by their ‘Director’, who turns out to be a ‘human mechanism’. But his mission to unite the two worlds is complicated by Elta’s implacable opposition. Fearing reunification will lead only to mutual annihilation, the woman he loves uses all of her spirited and determined energies to keep the two worlds apart.

And Ketan’s epic adventures are far from over. Switching dimensions with increasing ease, there are fast-action plot twists, unsuspected connections and new threads aplenty for him to unravel. Fire Land and Dark Land have been present as part of the novel’s outer landscape from the start. Now – escaping a Kronweld death-sentence, Ketan endures the hazardous extremes of both to reach a hidden valley-settlement founded by cybernetic immortal Igon – whose journey predicted Ketan’s own, and whose ghost-presence went before him. Conveniently there’s a heavily weaponised force already assembled there to counter imminent Statist incursions, leading the novel into its explosive climax. If the super-science clash of battle-machines has a distinctly 1940’s flavour, that’s exactly the quality George Lucas was purposefully recreating for his ‘Star Wars’ franchise. And in a closing Luke-Darth Vader moment it’s revealed that Matra was his grandmother, and Igon, his grandfather – ‘son of my son’, and that his destiny has been nudged and shaped all along by unsuspected forces. The apocalyptic destruction of the Kronweld planet, destabilised by the immense power of the energy-weapons unleashed by both sides, forces the two-world reunification. Ketan, with Elta by his side, will assist the healing, and thereby discover their own future together.

John Clute commends the novel’s ‘exciting narrative’ and its ‘lively variations on a number of favourite SF themes,’ judging this ‘long complicated parallel-worlds adventure’ as ‘probably his best’ (‘The Encyclopedia Of Science Fiction’). Reviewing the Pyramid paperback edition in ‘New Worlds’ (no.144, September-October 1964), ‘James Colvin’ – a Michael Moorcock alias, concedes that ‘the plot moves along well’ and is ‘good value, in spite of slightly dated style’ but is less impressed, ‘this must have been fairly original when it first appeared, but there’ve been a lot like it since, some better.’ Although it’s difficult to see how Jones could be held responsible for the flaws of books written later, it’s tempting to include Arthur C Clarke’s ‘The City And The Stars’ among them, with Ketan’s rebellion against the numb changelessness of Kronweld as a direct precursor to Alvin chafing at the frustrating restrictions of Diaspar.

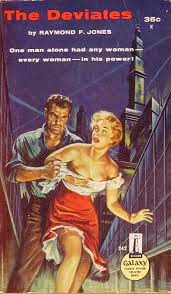

Raymond F Jones went on to write some fifteen other novels, among them are ‘The Alien’ (1951, as ‘Galaxy SF Novel #6’, World Editions), about an entombed extraterrestrial body discovered within the asteroid belt, ‘The Secret People’ (aka ‘The Deviates’, 1956 Avalon Books) about persecuted telepathic mutants populating a post-apocalypse world, and ‘The Cybernetic Brains’ (expanded from a 1950 ‘Startling Stories’ story, 1962, Avalon Books) which rewires human brains into computer-circuits, updating Eando Binder’s 1934 idea of ‘Enslaved Brains’ via cybernetics.

After being comparatively inactive through much of the sixties he returned to the field later with ‘such less interesting novels as ‘Syn’ (1969) and ‘The River And The Dream’ (1977).’ Although ‘not generally an innovator in the field’ according to John Clute, he nevertheless ‘produced solid, well-crafted hard-SF adventures’. Raymond F Jones died aged 78 in Sandy, in Salt Lake County, Utah in 24 January 1994.

No comments:

Post a Comment