ARTHUR SELLINGS:

POTENTIAL REALISED…

AND UNREALISED

Arthur Sellings was a writer who died in 1968 at the age of just

forty-seven. To David Pringle he was ‘a talented minor writer, but

is remembered with respect by some’. To John Clute, his ‘body of

work is modest in size and scope, but its literacy and firmness of

execution have been underrated’. Would there have been more,

and greater work to come, had he lived…?

Andrew Darlington examines the evidence…

THE HOAX SCHOLASTIC:

PHYSIOGNOMY OF THE STRAIGHT FACE

There are layers of confusion. Editor Peter Hamilton has lined up a novelette – “Categorical Imperative”, as the core text for his upcoming

‘Nebula no.17’, ‘it had already been paid for and set up ready for printing,’ then author Arthur Sellings pre-empts its publication by including it in his hardback collection –

‘Time Transfer And Other Stories’ (1956) bare months before the issue’s appearance. ‘I know how infuriating it can be to buy a magazine only to find that a considerable portion of its contents consist of stories you have read before’ bewails Hamilton. So he chases the writer up, who duly supplies a short-story alternative called “Cry Wolf”. The fact that the story concerns a serial practical-joker, a crazy-hobbyist, is maybe just a coincidence. Or perhaps not.

The fictional hoaxer is called Sammy Legg – as in ‘pull your leg’. The skeptical cop assigned to investigate his reported shape-shifting alien visitation is Lieutenant Yardley, as in ‘Scotland Yard’. But as Legg points out, in the original ‘Boy Who Called Wolf’ fable ‘there

was a wolf in the end’. Another layer is added when the so-called practical-joke is used as a weapon directed against authority. It can be a subversive device intent on ‘broadening men’s minds… de-mechanising their attitude towards the universe.’ The implication is that Legg’s stunts are what we’d now term prankster agit-prop – agitational propaganda of the ‘V For Vendetta’ variety. Yet, although he quotes from Thomas De Quincey’s 1827 essay ‘On Murder Considered As One Of The Fine Arts’, there’s nothing to suggest that Sellings’ politics lay in such radical directions. Instead, the playful theme is more the hook for a Police Procedural in which Legg’s murdered body indicates that maybe there really is a shape-shifting alien loose in the city.

It’s also worth bearing in mind that one of his pet aversions is quoted as ‘critics who complain of a dearth of humour in science fiction.’ He refutes the charge by pointing out the example of Henry Kuttner, Fredric Brown, Robert Sheckley and John Wyndham.

Sellings’ second contribution to the magazine – “Armistice”, in the following issue, seems superficially to be a more conventional Space Opera romp. A grim Pyle is representing the shattered remnants of defeated humanity by negotiating surrender terms with their supremely-rational conquerors, the Thunians. Yet when the aliens’ offer to relocate the five-hundred-plus Earthling survivors to a planet of the Procyon system because ‘two intelligent species cannot occupy the same world,’ Pyle realises their ‘rational’ solution is flawed in failing to factor in the irrational human drive that will dictate they use their new world to foment lethal revenge, and that – even if it takes generations, vindictive militarily tooled-up humans will be back to reclaim Earth. It will not be the age of reason, but sheer pig-headed obstinacy in refusing to accept the inevitable that will win through. Unreason, not logic and rationalism are the motivating forces that drive human success. A curious sentiment for a writer involved in scientific research to express!

‘The subconscious might be a dark waste-pit

but from its compost the seed of inspiration flowered…’

(“Armistice” in ‘Nebula No.18’)

By the time of this debacle Sellings was already a ‘well-known author’ as Hamilton grudgingly concedes. But in fact ‘Arthur Sellings’ was just one of the pseudonyms employed by Robert Arthur Gordon Ley – an alias drawn from his mother’s maiden name. He also wrote under the pseudonyms ‘Ray Luther’ and ‘Martin Luther’. He was born on 31 May 1921 in Tunbridge Wells, the son of Kent and Stella Grace Ley. As Mike Ashley notes ‘he moved early to London (W10) where he had a vivid recollection of seeing both

‘Metropolis’ (Fritz Lang, 1927) and

‘The Girl In The Moon’ (Fritz Lang, 1929) – two early and influential German SF films.’ Soon after, he ‘discovered HG Wells and the US SF magazines’ too – attracted by the extravagant cover-art of Frank R Paul. Meanwhile, following the war, he married Gladys Pamela née Judge on 18 August 1945, while working first as a customs officer.

But it was while employed as a government scientific researcher from 1955, that his work inspired his original forays into science fiction. His first published tale – “The Haunting”, appeared in the October 1953 issue of the curious British magazine

‘Authentic SF’. A hazy blue apparition seen at the Project Forward base is not a ghost, but a projected messenger from the future warning Controller Barlow of the disastrous consequences of their work, in time for him to curtail it. In doing so, altering the apparition itself. At just seven pages it’s a brief and promisingly effective tale of the unexpected.

Soon his work was also appearing in the US, something most of his contemporaries attempted, but few achieved. Trans-Atlantic sales involved airmail expense and time-delays that many with short-term financial needs found too problematic. Yet his second, third, fourth and sixth pro sales went to

‘Galaxy Science Fiction’, then to

‘Imagination: Stories Of Science And Fantasy’, followed by

‘Fantastic Universe’, and

‘The Magazine of Fantasy And Science Fiction’. The tipping point back was provided by the

‘Observer’ literary contest. In competition with the likes of Brian Aldiss’ “Not For An Age”, Sellings story – “The Mission” was commended by judge Angus Wilson into the top eighteen places, and anthologised. Such high-profile attention persuaded Michael Joseph to publish his

‘Time Transfer And Other Stories’, announced by EC Tubb as ‘a collection of stories which will do much to gain the medium greater literary merit.’ And enabling

‘New Worlds’ reviewer Leslie Flood to refer to Sellings as ‘now being among the top three British writers of short science fiction stories,’ alongside Arthur C Clarke and Eric Frank Russell – despite having only three stories published in the UK!

He set about redressing the situation with a spread of tales in

‘New Worlds’, the

‘New Writings in SF’ anthology-series… and his two appearances in Peter Hamilton’s

‘Nebula’. As he muses ‘the science fiction writer – well, he dreams anyway – lives dreams, writes dreams, sometimes, alas, has to eat dreams’ (in “The Tycoons”).

By the magazine standards of the time, his prose is fluent, his characters and dialogue well-defined. “Starting Course” in

‘New Worlds’ – later selected by Mike Ashley for inclusion in his

‘The Best Of British SF2’ anthology, is essentially a dialogue chamber-piece constructed around a nuclear-family unsettled by the intrusion of a well-mannered inoffensive android. It’s explained that, as in

‘Bladerunner’ (1982), androids are vat-grown to colonise planets humans have become too insular and complacent to visit. Although that turns out to be not exactly the case. Anyway, that’s largely background to the freighted interplay of family dynamics, which it is the android’s role to destabelise. ‘You see, Eddie, your job wasn’t really to adjust to people – it was to

disadjust

them. Not so much your finishing course as their starting course.’ There’s considerable pathos to the character’s final unexpected parting.

It’s a good example of what John Clute calls the way Sellings ‘integrated literate investigations of character into SF storylines of some conventionality’ (in

‘The Encyclopedia Of Science Fiction’ edited by Peter Nicholls, Granada, 1979). Best known for his well-crafted portraits of adaptability under stress, Sellings’ stories are noted for their humor, suspense and attention to plot and character. Each separate and complete in itself. His use of ruptured prose in “Birthright” (

‘New Worlds’, no.53, November 1956) anticipates both Anthony Burgess’ ‘Nadsat’ and Russell Hoban’s

‘Riddley Walker’ (1990) as an experimental device that attempts to capture the mental evolution of a genetically-engineered human designed to colonise a heavy-gravity ammonia-atmosphere planet.

Published some years before the SF ‘New Wave’ it clearly indicates that Sellings was more than capable of literary innovation when such extremism is required by the demands of the plot. So much so that Langdon Jones, a writer closely associated with the New Wave, could claim ‘I have always considered Arthur Sellings to be a greatly underestimated and neglected writer’ (reviewing the novel

‘The Uncensored Man’, 1964). More specifically, he notes that ‘this novel, I think, tends to illustrate the direction in which SF is going. The book is concerned with the mind. There are no rockets, no galactic strife, nothing save two men and a drug, but the resultant story is exciting, readable, and science fiction. Sellings extrapolates on ideas of Freud and Jung, incidentally producing about the first SF book I have ever seen which does not completely misrepresent Freud’s ideas… this book is what SF should be, and all too often, is not.’

‘Obviously Science Fiction, like any other genuine literary form, must evolve’ Sellings himself argues in a

‘New Worlds’ profile (no.49, July 1956). ‘It was easier in the old days – easier to find ideas, to stop in the middle of everything for a dissertation on Jupiter’s moons. The modern way, starting a story in the middle of a future- or other-world environment and taking it from there is a challenge to the writer. It isn’t always easy, but it is fun.’ ‘Science Fiction is a literature of ideas’ he persists in the

‘New Worlds’ ‘Postmortem’ letter column (no.81, March 1959), ‘I don’t mean pseudo-scientific gimmicks, but new viewpoints, new probings into the unknown – even new experiments in style. Because if the style is fresh it can’t help but invigorate even an old idea… I am convinced that science fiction has a great deal more to say than it has already.’

Yet he was not always attuned to the social and literary changes happening around him. He wrote another long and detailed letter to

‘New Worlds’ (no.118, May 1962) decrying the new openness. ‘While it would be stupid to deny the importance of sex both in life and literature, there is currently far too much emphasis on it – a decadent, almost morbid, preoccupation with sexual functions. I’m no prude, I hope; one of the best novels I have read in recent years is

‘The Ginger Man’ (by JP Donleavy, 1955). But sex is dragged in by the short hairs so often in so many books as to cause revulsion, a nausea at a continual imbalance. It is an imbalance found in much of the best contemporary serious literature.’

Nevertheless, when his story “The Proxies” was broadcast as a radio play on the BBC Home Service in June 1960, the adaptation changed the main character from a man to a woman, a scientist at that. ‘Writers are supposed to be annoyed with such tampering with their work’ he comments. ‘I was only annoyed that I hadn’t recognized myself that the character’s reactions in my own story were basically feminine. I was guilty of a blind plot.’ Going on to generously concede that ‘I think we SF writers are guilty of under-estimating both the place of women in SF and their potential in the world… I think that too many of us are similarly guilty too often.’

But he probably reached his widest audience when his satirical short story “The Tycoons” was adapted by screenwriter Bruce Stewart into an episode of ABC-TV’s groundbreaking

‘Out Of This World’ series. With each of thirteen black-and-white tales introduced by the macabre presence of Boris Karloff, I was certainly one who enthusiastically watched the teleplay, directed by Charles Jarrott, when it was broadcast at 10pm on the Saturday night of 22 September 1962. There’s humour and pathos ‘when zealous taxman Oscar Raebone (Ronald Fraser) calls unexpectedly on the Project Research Company, a firm making novelty dolls, and encounters the Tycoons, mysterious strangers led by Abel Jones (Charles Gray), he turns up a situation that can only be described as out of this world…’ As the magazine blurb had earlier explained, ‘their business was to produce dancing dolls, but behind the scenes they were an alien organisation waiting to take over Earth.’ But while the Dinkum Doll was a cover for their subversive activities, Raebone’s enthusiastic championing of the product makes it so successful that the aliens abandon their plans, and decide to stay and enjoy the benefits of their new world.

By the time “The Tycoons” was first published in

‘Science Fiction Adventures’ (no.6, January 1959), editor John Carnell was describing Sellings as an ‘antiquarian art-dealer, bookseller bibliophile, and short story writer’ and something of a ‘minor tycoon’ in his own right because ‘he owns several shops.’ After its TV adaptation he could probably extend that job-definition further.

The magazines of the period were a breeding ground for emerging writers to perfect their skills and hone their craft, before up-gearing into novels and the more rarified lit-celebrity they bring. And unlike many writers of his generation, Sellings was able to vault the event horizon into the post-New Wave titles. Although he was never destined to follow the path of Brian Aldiss, Christopher Priest or JG Ballard. He produced four novels, plus one as ‘Ray Luther’ (a near anagram of his real name!), and another published after his untimely death. Some consider this posthumous

‘Junk Day’ to be his best work, as indication of his escalating potential. But to David Pringle he remains ‘a talented minor writer, but is remembered with respect by some’ (in

‘The Ultimate Encyclopaedia Of Science Fiction’ (Carlton Books, 1997), and to John Clute, his ‘body of work is modest in size and scope, but its literacy and firmness of execution have been underrated.’

But we’ll never know if there were greater things to come. ‘Arthur Sellings’ Ley died early of a heart attack on September 24, 1968 in Worthing, aged just forty-seven. He left a widow and many friends. ‘A fine craftsman’ said

‘New Worlds Quarterly no.2’, ‘his work was admired greatly by his fellow writers.’ In the circumstances, what he leaves is more than enough.

ARTHUR SELLINGS:

POTENTIAL REALISED…

AND UNREALISED

1953 –

The Haunting (‘Authentic Science Fiction Monthly no.38’ October 1953 illustrated by Gerald, collected into ‘Time Transfer And Other Stories’, Michael Joseph 1956, Compact paperback 1966) ‘Was it a ghost, the apparition that knew so much of Barlow’s new project?’ editor HJ Campell writes ‘Arthur Sellings is another new science fiction writer we have discovered. His ‘Haunting’ gives us a fresh slant on apparitions. Maybe after you’ve read this story you won’t be afraid of them any more. Or maybe you’ll just start believing in them?’

1954 –

The Boys from Vespis (‘Galaxy Science Fiction Vol.7 No.5-A’ February 1954) ‘It was all just a frightful mistake, but try convincing the Earthgirls that it was!’ illustrated by Kossin

1954 –

The Departed (‘Galaxy Science Fiction Vol.8 No.5’ August 1954) ‘Let the dead past bury its dead? No… leave the dirty work to the unborn future!’ illustrated by Fleminger

1954 –

A Start in Life (‘Galaxy Science Fiction Vo.8 No.6’ September 1954, novelette collected into ‘Time Transfer And Other Stories’, Michael Joseph 1956) ‘What a problem for a robot… having all of the answers, but not knowing when to give them!’ illustrated by Sentz

1954 –

The Cautious Invaders (‘Imagination: Stories Of Science And Fantasy’ October 1954) cover-art illustrates ‘The Laughter Of Toffee’ by Charles F Myers

1954 –

The Age of Kindness (‘Galaxy Science Fiction Vol.9 No.2’ November 1954, collected into ‘Time Transfer And Other Stories’, Michael Joseph 1956) ‘There was only one way for Bruno to be like everybody… get rid of all of them!’ illustrated by Dick Francis

1955 –

The Mission (‘AD 2500: The Observer Prize Stories 1954’, William Heinemann) anthology made up of the twenty-one best entries submitted to the ‘Observer’s Short Story competition, chosen by Angus Wilson

1955 –

The Figment (‘Fantastic Universe’ February 1955, collected into ‘Time Transfer And Other Stories’, Michael Joseph 1956)

1955 –

Escape Mechanism (‘Fantastic Universe’ vol.4 no.1, August 1955, collected into ‘Time Transfer And Other Stories’, Michael Joseph 1956)

1955 –

The Proxies (‘If’ October 1955, collected into ‘Time Transfer And Other Stories’, Michael Joseph 1956) Adapted by Anthony Juan Skene as a radio play broadcast on BBC Home Service, 14:30, 18 June 1960. ‘Radio Times’ comments ‘Even today there are many jobs that machines can do better and faster than their creators, and some people are tempted to look ahead with trepidation. Just suppose that machines could really think, suppose one day they had it in their power to take control. This play suggests it might not be altogether disastrous,’ produced by Michael Bakewell

1955 –

Jukebox (‘Fantastic Universe’ December 1955, collected into ‘Time Transfer And Other Stories’, Michael Joseph 1956, ‘More Tales Of Unease’ edited by John Burke, Pan Books 1969)

1956 – ‘

TIME TRANSFER AND OTHER STORIES’ (Michael Joseph 1956 as 12s 6d, reviewed in ‘New Worlds no.47’ May 1956) collects ‘The Haunting’ from ‘Authentic’ plus new stories ‘

From Up There’, ‘

The Wordless Ones’, ‘

Control Room’, ‘

Soliloquy’ and ‘

The Awakening’ plus previously USA-only titles ‘The Proxies’ from ‘If’, ‘A Start In Life’ from ‘Galaxy’, ‘Pentagram’ from ‘Satellite SF’, ‘The Figment’ and ‘Escape Mechanism’ from ‘Fantastic Universe’. The UK paperback edition eliminates five stories at the author’s discretion. Also reviewed – presumably by editor EC Tubb, in ‘Authentic SF no.70’ (15 June 1956) as ‘a collection of sixteen short stories all well-written and all highly entertaining. They range from the thought-provoking moral in ‘

The Age Of Kindness’ to the delightful humour in ‘

Categorical Imperative’ and ‘

The Boy Friends’ (aka ‘The Transfer’), with a peculiar touch of horror in ‘

Jukebox’ and ‘

Time Transfer’ (1966 Roberts & Vintner Compact SF paperback)

1956 –

Pentagram (‘Satellite Science Fiction’ October 1958) collected into ‘Time Transfer And Other Stories’, Michael Joseph

1956 –

The Masters (‘New Worlds no.49’ July 1956), plus ‘Writers Profile’, Hedley and estranged wife Elsa stranded on planet in a city of robots. Despite the robots catering to their every need, he kills her with an H-E gun when she adapts a robot to resemble her lover George Manders, then kills himself. The robots inter their remains in a tomb alongside the ‘three hundred and seventy nine million, five hundred and twenty thousand, eight hundred and sixty seven’ others they’d failed to bring happiness to!

1956 –

The Warriors (‘New Worlds no.50’ August 1956) ‘Contact between differing races can never entirely be a one-way affair where the dissemination of knowledge is concerned. Each side will always learn something from the other, but it will depend to a large extent upon the interpretation of the knowledge exchanged which side will ultimately benefit the most,’ peaceful vegetarian humanoid aliens learn hostility from bickering couple Linda and Mike

1956 –

Birthright (‘New Worlds no.53’ November 1956), illustrated by ‘Eddie’, John Carnell writes ‘every once in a while we publish a story whereby it is not possible to give any indication of the plot in the caption without completely spoiling it for the reader. Arthur Selling’s latest story is one such and once again shows his versatility as a writer’. Collected into ‘The Long Eureka’ Dennis Dobson 1968

1956 –

The Category Inventors (‘Galaxy Science Fiction Vol.11 No.4’ February 1956) novelette ‘There was security for all in this well-run world – but what happened to a man who tried to get ahead could never happen to a robot!’ illustrated by Emsh

1956 –

One Across (‘Galaxy Vol.12 No.1’ May 1956, collected into ‘The Long Eureka’ Dennis Dobson 1968) ‘Doing puzzles is an escape, eh? Then how was it Norman found himself so boxed in?’ illustrated by Cal

1956 –

Cry Wolf (‘Nebula no.17, July 1956) ‘He had made a hobby of practical joking in a world of un-amused officialdom. Was he to get the last laugh also?’ illustrated by D McKeown

1956 –

Verbal Agreement (‘Galaxy Vol.12 No.5’ September 1956, novelette collected into ‘The Long Eureka’ Dennis Dobson 1968) ‘Some problem to give an unsuccessful poet – what would the Vernans want one-half so precious as the skins they wouldn’t sell?’ illustrated by Dick Francis

1956 –

Armistice (‘Nebula no.18’, November 1956) ‘Assured of their own supremacy, the Thunians were ready to sign their own death-warrant’

1957 –

Brink of Madness (‘Super-Science Fiction no.3’ April 1957) cover-art by Kelly Freas, issue also includes Robert Silverberg and Harlan Ellison

1957 –

Fresh Start (‘New Worlds no.61’, July 1957) ‘Rehabilitation for a person suffering from amnesia is a difficult task at the best of times, but somewhere during the course of therapy the patient begins to help himself’, he is not amputee Sam Bishop in Greenville, it’s all an elaborate construct by sympathetic aliens

1958 –

Blank Form (‘Galaxy Vol.16 No.3’ July 1958, collected into ‘The Long Eureka’ Dennis Dobson 1968) ‘They knew there was an answer somewhere… now all they had to do was find the question’ illustrated by Martinez

1958 –

The Shadow People (‘New Worlds no.73’ July 1958) failed artist Paul Nash – ‘Davy’s my brush-name. There’s already been one Paul Nash’, leases his spare room to mysteriously pale Mr & Mrs Smith, who turn out to be from future-time 2149, escaping ‘the end of the world’. She’s already seen his painting ‘Study By Snowlight’ which she inspires, which ‘in our time hangs in a museum’

1958 –

Flatiron (‘New Worlds no.77’ November 1958) when Shand assists an inter-dimensional being ‘piteously rampant and radiating distress’ it repays him by gifting humans with uniformity, everyone becomes him and his wife Jean

1958 –

Limits (‘Science Fantasy no.32’, December 1958) an affectionate reverie about run-down provincial theatre ‘The Regency’ and supernatural French Mime artist, Jean Victoire, as a metaphor for creativity itself, ‘an artist sets limits on his work – because his art is the struggle against them. Without them there would be no art’

1959 –

For The Colour Of His Hair (‘New Worlds no.79, January 1959) in no.81 he writes ‘in my recent ‘For The Colour Of his Hair’ I raised an objection to a theory which 99.99% of science fiction readers (and writers) seem to accept unquestioningly – that of evolution by gradual mutation and natural selection. It is not my own objection; the quotation I made in the story is from an actual book published over fifty years ago, but it has been stated before and since then. The story ‘explained’ it away in science fiction terms, but there seems to be a vested interest against admitting this objection; see, for example the way JBS Haldane ‘answered’ it in his ‘Possible Worlds’. I have yet to see it answered satisfactorily…’

1959 –

The Tycoons (‘Science Fiction Adventures no.6’ January 1959) art by Brian Lewis. Adapted by Bruce Stewart for ABC-TV’s ‘Out Of This World’ anthology series broadcast 22 September 1962 ‘When zealous taxman Oscar Raebone (Ronald Fraser) calls unexpectedly on the Project Research Company, a firm making novelty dolls, and encounters the Tycoons, mysterious strangers led by Abel Jones (Charles Gray), he turns up a situation that can only be described as out of this world…’

1959 – ‘New Worlds’ no.81, March 1959. Detailed three-page letter in the ‘Postmortem’ section

1959 –

The Scene Shifter (‘Star Science Fiction Stories no.5’ May 1959, collected into ‘The Long Eureka’ Dennis Dobson 1968)

1959 –

The Outstretched Hand (‘New Worlds’ no.83, May 1959) ‘if we were given the opportunity of living part of our life over again – picking out some turning point where the probability lines diverge – how much difference would it make in the long run? How much Free Will are we allowed during a lifetime?’ an intriguingly brief tale, psychiatrist Dr Meyer uses narcosis to allow Grant to visit his child-self and encourage his lost art-ambitions, only to find that nothing changes – was he always destined to a safely prosperous business career despite his creative yearnings?, collected into ‘The Best Of New Worlds’ edited by Michael Moorcock, Compact Books 1965)

1959 –

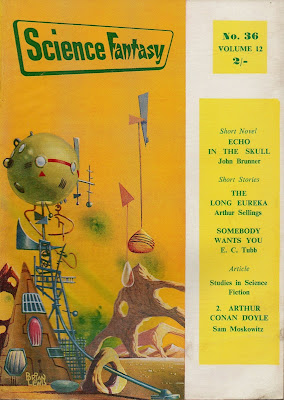

The Long Eureka (‘Science Fantasy no.36’ August 1959), collected into ‘The Long Eureka’ Dennis Dobson 1968. Unusual structure, Isaac Reeves invents the Elixir Of life in 1820, but fails to convince anyone as plot leap years from 1822 to 1827, 1830, 1832, 1838, 1842, 1843, until 2103 with first starship to Proxima Centauri, he arrives 2307 to gift a new race with his serum, only to learn they are already immortal

1960 – ‘

Film Review: The Time Machine’ (‘New Worlds no.100’ November 1960) ‘surely this should be a very good film. Unhappily it isn’t, though it is not easy to say just why’

1961 –

Starting Course (‘New Worlds no.102’ January 1961, ‘The Best Of British SF2’ edited by Mike Ashley, Orbit 1977) android Eddie A-Smith has an unsettling effect on the Trendall family during his integrating-period with them, with racist overtones Dad accuses the ‘damn android’ of an inappropriate relationship with 16-year-old daughter Kathy – except android’s are neuters who ‘don’t breed’. And 12-year-old son Steve is motivated to nudge the family out of complacency to sign up for the Procyon Three colonisation project – which is the android’s real purpose. This story would be ideal for a ‘Twilight Zone’ episode

1961 – ‘Essay: Where Now?’ (‘New Worlds no.111’ October 1961)

1962 –‘Letter: On William F Temple’ (‘New World no.118’, May 1962)

1962 – ‘

TELEPATH’ (novel, US Ballantine Books with Richard Powers cover-art, alternate title ‘The Silent Speakers’ Dennis Dobson 1963), ‘Was He Unique, Or A Forerunner Of The Next Development In Man?’, it ‘builds a gradual and convincing picture of a man’s discovery of limited telepathic ability’ (John Clute). ‘Powerful’ according to Mike Ashley

1964 – ‘

THE UNCENSORED MAN’ (novel, Dennis Dobson 1964, reviewed by Langdon Jones in ‘New Worlds no.146’), ‘Mark Anders, the hero, works in a secret weapons establishment. At the opening, we find his marriage on the point of breaking up, and his mind filled with doubts about his work. Then an epileptic boy and a computer give the clues that lead him on the trail to his eventual discovery, a discovery of universe-encompassing implications,’ it ‘transfers its protagonist by drugs into another dimension where he develops his previously masked psi powers and meets dubiously superior forms of life’ (John Clute)

1964 –

The Well-Trained Heroes (‘Galaxy’ June 1964, novelette collected into ‘The Long Eureka’ Dennis Dobson 1968)

1965 – ‘

The Power Of Y Parts 1 and 2’ (‘New Worlds no.146 and no.147’ serial in January and February 1965, ‘SF Reprise 2’ edited by Michael Moorcock, Compact Books 1966) ‘Plying – or Transdimensional Multiplying to give it its full name – wasn’t such a revolutionary invention after all. There were limits to what the machine could do – or so it seemed. When art-dealer Max Afford discovered he had a mild psi-power he discounted it a useless. But was it?’ no.146 also includes Langdon Jones review of ‘The Uncensored Man’

1965 –

The Tinplate Teleologist (‘Worlds Of Tomorrow’ Vol.3 no.3 (15), September 1965) with art by Brock, edited by Frederik Pohl

1966 –

Gifts Of The Gods (‘New Writings In SF 9’ edited by John Carnell, Dennis Dobson) a touch of whimsical humour when Bryan Dudley and his wife Gwen find eight alloy cylinders in their New town garden, then a glut of other multi-coloured inexplicable ‘gifts’. Interdimensional beings are using Earth as a landfill, but what happens when they begin to dump their surplus population too?

1966 –

That Evening Sun Go Down (‘New Worlds no.166’ September 1966) challenging experiment in which the first two pages are in fractured language – ‘yet more black he sing. Painsong, that one note We shiver at. Rotate or one, painsong touch balmtackle, two meet like great holy oneinmany of universe. But this rotate I feel only pain.’ It is a fragment of a contested script found by a human tribe who mistake the insectoid alien conqueror Great Ones of the text with their own ancestors, but no, they are ‘the Puny’. This issue also includes editor Michael Moorcock’s ‘Behold The Man’, plus New Wave JG Ballard, Barrington J Bayley, Aldiss, Brunner and Thomas M Disch

1966 – ‘

THE QUY EFFECT’ (novel, Dennis Dobson, December 1966, US Berkley Medallion 1967) 144-pages, cover-blurbed ‘A New SF Novel About A Shocking Discovery That Changed All Of The Physical Laws Of The Universe’, it ‘combines the invention of a new form of power with a love story involving its struggling inventor’ (John Clute), ‘…it was so powerful that in one instant it obliterated an entire building. Only the concrete floor and stumps of walls remained… its implications were so revolutionary as to render all past scientific concepts obsolete... which only served to alienate the entire scientific community against its inventor, Aldophe Quy’

1967 –

The Key Of The Door (‘New Worlds no.172’ April 1967 aka ‘New Worlds Quarterly no.2’ edited by Michael Moorcock, Sphere Books 1971) a clever and amusing HG Wells pastiche in which Cyril suspects that his son Godfrey has been using his secret time machine invention for assignations with Melinda in 1985, whose granddaughter is his own mistress in 2035!

1967 – ‘

INTERMIND’ (novel as by ‘Ray Luther’, Banner October 1967, Dennis Dobson October 1969) cover-blurbed ‘An Extraordinary Spy Novel Of Tomorrow’, in which a secret agent is injected with another person’s memory to pursue a complex case

1968 –

The Last Time Around (‘New Writings In SF 12’ edited by John Carnell, Corgi 1968) reprinted in ‘If’ November-December 1970. Carnell writes ‘there have been many fascinating stories concerning the apparent paradox of subjective and objective time, but none quite so poignant or explanatory as the one Arthur Sellings presents here.’ Grant ‘spans centuries’ piloting DCP ships (Direct Continuum Propulsion) returning to Earth as ‘a stranger in a foreign country’, until he and Etta Waring fall in love. To bridge the time-difference for his next trip she clones herself so they’ll still be age-compatible

1968 – ‘

THE LONG EUREKA’ (collection, Dennis Dobson, March 1968) first UK publication for American material – ‘Blank Form’, ‘The Well-Trained Heroes’, ‘Verbal Agreement’ and ‘One Across’ from ‘Galaxy’, ‘The Scene Shifter’ from ‘Star Science Fiction Stories’, plus ‘The Long Eureka’ from ‘Science Fantasy’ and ‘Birthright’ from ‘New Worlds’, also includes previously unpublished novelettes Homecoming and Trade-In

1968 –

Crack In The Shield (‘The Magazine Of Fantasy And Science Fiction’ Vol.34 no.1, January 1968) ‘Special 200th Issue’ with Harlan Ellison, Fritz Leiber and Isaac Asimov

1968 – ‘

THE POWER OF X’ (novel, Dennis Dobson December 1968) ‘a neat variation on the matter-duplicator theme’ according to Brian Ash in ‘Who’s Who In Science Fiction’, Pan 1976. ‘Fascinating’ according to Mike Ashley. A short novel that takes place in 2018 when ‘transdimensional multiplying’ or ‘Plying’, a highly guarded government monopoly, can make perfect copies of items. Max Afford, owner of the ‘Gallery O’ art gallery, realises he can tell an original Matisse from the copy just by touching it. At an auction he buys a portrait of the grandfather of the current President of the European Federation of States. His Aunt takes him to a reception at the renamed Buckingham Palace, now called the Europa Palace where he intends giving the painting to the President (an infant in the painting). But when Max shakes hands he realises the President is also a copy. Kidnapped and put into an asylum Max wakes to find out his kidnapper is his Aunt along with former Senator Guy Burroughs. They must break into the Palace to bring the conspiracy to light.’ Serialised in ‘New Worlds’ nos 146 and 147

1969 –

The Legend And The Chemistry (‘The Magazine Of Fantasy And Science Fiction’, Vol.36 no.1 (212), January 1969) issue also includes Samuel R Delany, Harlan Ellison, Barry N Malzberg (as KM O’Donnell)

1969 –

The Dodgers (‘Fantastic’ Vol.18 no.4. April 1969) issue also includes John Sladek, Walter M Miller, John Jakes and two by Barry N Malzberg (as by KM O’Donnell and Robin Schaefer)

1969 –

The Trial (‘New Writings In SF 15’ edited by John Carnell, Dennis Dobson 1969) reviewing the collection in ‘Vision Of Tomorrow no.5’ Kathryn Buckley writes ‘it would be impossible to talk about ‘The Trial’ without feeling very saddened by the premature death of Arthur Sellings, which has thinned the ranks of British science fiction writers. By the ‘In Memoriam’ box at the front it is obvious that the collection had gone to the printers at the time of his death so that this story is probably amongst the last he wrote. Characteristically, it is deftly and skillfully handled. Communication, or the lack of it investigated in a very well-told story that question’s man’s arrogant missionary obsession, however well-intentioned, and once again we have aliens portrayed sympathetically’

1970 – ‘

JUNK DAY’ (novel, Dennis Dobson April 1970, Leonaur paperback 2007) ‘his finest novel was his last, Junk Day, a post-holocaust tale set in the ruins of his native London and peopled with engrossing character types… perhaps grimmer than his previous work but pointedly more energetic’ (‘The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction’), cover-blurbed ‘After The Day Of The Apocalypse’, an unspecified catastrophe has left civilisation in ruins, bands of survivors pick over the detritus, as a new order is emerging, with the nascent society brutally guided by superior force – the threat of violence and the barrel of a gun. Into this world comes Bryan – a loner, an artist with a vision all his own and a belief that a new world can only emerge from co-operation and culture. With Vee, the last survivor of her Convent, and self-styled autocrat Barney (a near-anagram of Bryan), will belief in the essential goodness of mankind win the day? Or will brutality rule?