Panther UK paperback, 1968 ISBN 0-586-02420-4)

It opens in the simple rural community of New Tassel, a ramshackle settlement of two-hundred-and forty-seven folk living on the northern shore of Lake Superior as the lake itself recedes to uncover new fertile arable land. With stern ‘strong-willed bigot’ father Anderson, and his two sons, Neil who is lumbering, mean and brutish, and younger more rebellious half-brother Buddy. Among the simple hardworking folk, the ‘Prodigal’ Buddy is the only one to have ventured into the cities of the greater world beyond, to University where the streets were swift-flowing rivers of light… before the fall. Now there are no more cities. There is only the endless green of the alien plant growths that have smothered the planet, stifling all rival forms of life. ‘They had come of a sudden in April of ’72, a billion spores… and within days every inch of ground, farmland and desert, jungle and tundra, was covered with a carpet of richest green.’

Neil is married to Buddy’s flirtatious former-girlfriend Greta, who gets wistfully nostalgic for the world they’ve lost. Buddy is married to mousey pregnant Maryann, survivor of a massacred Marauders party up from Minneapolis. The Anderson’s continue much as they always have done, simply adapting their methods by tapping bucketfuls of oozing honey-like sap from the towering smooth-skinned plants that soar to six-hundred feet, and using the sap to fertilise their patient rows of maize in plots hacked out of the growth. Until the next stage of the global take-over begins with the arrival of the ‘incinerators’, signalled when escaping cattle are reduced to ash, along with pursuing younger Anderson son, Jimmie. This levelling of ‘remaining artifacts’ (Disch’s spelling) prefigures the final ‘Good-Bye Western Civilisation’ phase.

Life on Earth is a precarious thing. Humans have enjoyed ten-thousand years of relative stability. There’s a playful frisson to conjecturing that this condition will not continue indefinitely. The cover-art for the 1979 Panther paperback edition announces ‘The Genocides’ as ‘The Best Post-Disaster Yarn Since ‘The Day Of The Triffids’,’ evoking certain obvious parallels. There’s a suspicious familiarity that the scenario encroaches other post-apocalypse novels, particularly George R Stewart’s 1949 ‘Earth Abides’, even as it assumes elements of Wyndham’s ‘School of Cosy Disaster’ SF. As the ever-perceptive Brian Aldiss points out, although ‘Disch is an American. ‘The Genocides’ is curiously English. It is another story of a dwindling community which has survived a catastrophe, although Disch handles it in his own way’ (in ‘SF Impulse’ no.11). Yet there are other even more precise precedents. There’s a suspiciously similar plot to ‘Earth Our New Eden’ by veteran writer FG Rayer in ‘Authentic Science Fiction no.20’ (15 April 1952), where the Earth is seeded by alien plants, producing a ‘Green Twilight’. ‘The tops of the plants spread like giant ferns, each interlacing with its neighbours. Behind the precipice of alien growth, away to his right, the sun was outlined as a dull red orb. The patchy cloud above was ruby tinted, fading away to purple and black in the east. The whole made a scene so strange, so terrifying, that Peter felt his limbs grow cold’. The machines stop, with ‘Earth rapidly becoming uninhabitable for men’.

As Rayer’s protagonists struggle to survive in this re-made world of final blackout they encounter images that eerily anticipate Disch. ‘Never since prehistoric times had there been such plants on the Earth, he thought, amazed. Now, once again, was an abundance of such vegetation as had existed when the great coal-beds of the planet had been laid down. He might have imagined himself plunged back millions of years into prehistory, but for one thing – the plants were alien...’

Born in Iowa in 1940 Thomas Michael Disch grew up in Minnesota, and was educated at New York University. He became a freelance writer in 1964 after working for a year in advertising, to be soon marked out as ‘a noted arrival in the SF field of the 1960s,’ according to Brian Ash (in ‘Who’s Who In Science Fiction’, Sphere, 1976). ‘The Genocides’ was Disch’s first novel, preceded by a series of impressively powerful short stories that gained him a strong reputation as an innovator. Yet strangely, for a supposedly New Wave classic, Disch also employs strong religious overtones, as early as the title-page quote from the biblical book of Jeremiah 8.20. ‘Anderson knew that the same angry and jealous God who had once before visited a flood upon an earth that was corrupt had created the Plants and sown them. He never argued about it.’ Perhaps this attitude is intended to reflect the unsophisticated morality of stoic rural people?

The novel only becomes ‘New Wave’ when that religiosity is turned around, so that it’s viewed not only as a conscious part of the post-apocalypse genre tradition, but also as a knowing satire of them. Disch shifts the narrative focus, with each of the core figures given voice at different times. There are even brief sequences seen from the alien perspective; a date for the Estimated Completion Of Project (2 February 1980), and an instruction for the entire incineration of surviving terrestrial life-forms by 4 July 1979, exterminating human ‘indigenous mammals’ in the ‘Duluth-Superior artifact’. That the aliens are clearly working to a schedule not too far removed from human corporate mentality, with reports of ‘mechanical failures’ sent to the ‘Office of Supplies’ complete with appendaged carbons! could be seen as detracting from the existential crisis afflicting the planet. Might it not have been better to leave the alien thought-processes impenetrable, as FG Rayer had done, with the effect of his story heightened by the imprecisely-glimpsed but never-quite-seen extraterrestrial denizens of the alien jungle that Earth has become? But that is clearly not Disch’s intention. That their completion date coincides with ‘Independence Day’ – the movie had yet to happen, is further evidence of a satiric agenda.

When the community share a grotesque family Thanksgiving meal that consists of nine-inch-long sausages recycling the human remains of slaughtered scavengers, there’s the moral justification of the ‘Donner party’ and the wreck of the ‘Medusa’ where survivors had also descended to cannibalism, with the implied ritual bonding of collective complicity in the murders that eating represents. But surely there’s also the darkest most repellent of back humour in there too? In balance there’s also a clear understanding of the interactivity of the natural world and its food-chain, as the extreme monoculture of alien plants smother all else, the world’s rich biodiversity goes into a freefall towards extinction, and even the soil, deprived of nutrition, turns to gritty dust that blows away. While colder winters result from climate-change induced by loss of carbon dioxide as the plants alter the balance of the atmosphere.

Meanwhile – switching focus, Jackie Whythe and mining-engineer ‘Jerry’ Jeremiah Orville watch as ‘incendiary mechanisms’ burn Duluth to the ground. Initially intoxicated by a strange sense of elation as he’s liberated from his formerly paunchy dead-end life-prospects, Jerry ‘learned to be as unscrupulous as the heroes in the pulp adventure magazines he’d read as a boy – sometimes as unscrupulous as the villains.’ After surviving in the safe-deposit vault of the First American National Bank with a store of scavenged cans and jars, they escape on bicycles, only to be stopped by former-nurse Alice Nemeron – ‘if you get sick, I can tell you the name of what you’ve got.’ They join her band of ‘Wolves’ travelling northeast on Route 61, until they’re overwhelmed by the Anderson Clan. When only Jerry and Alice survive, he pledges vengeance.

In the grip of freezing snowbound winter New Tassel’s final cow dies giving birth, and then three spherical incendiaries reduce their sheltering common-room to ash, leaving them refugees. When the child Blossom leads them to a cave on the lakeshore that she remembers from a childhood incident, they huddle inside. It’s there that Jerry investigates some plant-roots that have grown down through the cave-roof and discovers not only that they’re hollow but that they’re interconnected into an endless network of navigable passages, with fruiting tubers large enough to provide a sanctuary rich with edible fibres, where they become drunk on an orgy of oxygen. The thirty-one survivors are reduced to ‘the puppets of necessity,’ little more than termites, ‘they were worms, crawling through an apple.’

Disch’s prose-style is highly readable, as he delineates the group’s internal rivalries, the strongly-sketched characters all the more believable for their flaws. Orville’s informed resourcefulness, backed up by Buddy’s support, erodes Anderson’s strict Bible-sanctioned authority, as they encounter hordes of rats driven to equally extreme measures. There’s a rebellion, and a breakaway group led by Greta. Then the crisis is tipped further into critical when an already ageing Anderson is gangrenously infected by a rat-bite, Neil suffocates him before he can nominate Orville as his successor, then has witness Alice thrown down a deep root-tunnel to die. Anderson’s death robs Orville of his long-delayed revenge, and he’s tormented by Jackie Whythe’s accusing ghost images. Yet Buddy and Orville form an uneasy temporary alliance with Neil and Blossom, until Neil is destroyed in madness. There’s implied incest, corpse desecration and the grotesque obesity into which Greta has devolved, as the plant-sap goes into spate and on the surface far above them the harvest is being prepared. They eventually return to the scorched-earth surface where a new crop of plants is already germinating.

As Disch explained to Charles Platt, ‘it was always aesthetically unsatisfying to see some giant juggernaut alien force finally take a quiet pratfall at the end of an alien-invasion novel. It seemed to me to be perfectly natural to say, let’s be honest, the real interest in this kind of story is to see some devastating cataclysm wipe mankind out. There’s a grandeur in that idea that all the other people threw away and trivialised. My point was simply to write a book where you don’t spoil that beauty and pleasure at the end’ (in ‘Who Writes Science Fiction?’, 1980, Savoy Books). For the epilogue is called ‘The Extinction Of The Species’. There’s no upbeat ending. This is the New Wave shock. Earlier eco-disaster novels closed on a note of new hope, the dawn of new beginnings. Even for JG Ballard his characters transfigure into an acceptance of an Earth that’s undergone metamorphosis into surrealism.

Not for Disch. Not for ‘The Genocides’. There’s no meaning, no salvation. Even the novel’s title is inaccurate – although an obvious genocide occurs, it is less a targeted focused genocide, more an irritable brushing aside. The implications are disturbing. Unlike Anderson’s belief in divine purpose and destiny, life on this planet happened as the result of a random accident of no great significance, and it can be snuffed out in a way that is equally random and insignificant. ‘It wounded his pride to think that his race, his species, his world was being defeated with such apparent ease. What was worse, what he could not endure was the suspicion that it all meant nothing, that the process of their annihilation was something quite mechanical: that mankind’s destroyers were not, in other words, fighting a war but merely spraying the garden…’

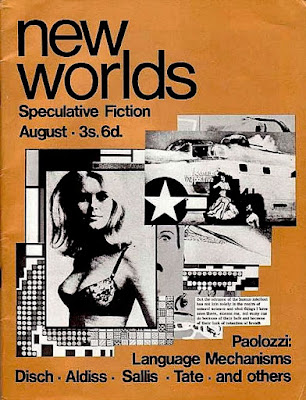

Although there would be further well-received novels, Thomas M Disch was never an easy fit within the SF genre, utilising its tropes instead for intellectual literary games. Readers were quick to spot that he marched to a different drum from the writers they were familiar with, and while celebrated by the ‘New Worlds’ coterie, others failed to warm to the high chill factor of his new realism. ‘Acerbic yet jolly, terse yet lushly Victorian, sardonic yet unwillingly romantic, ruthlessly modern yet operatic’ according to his entry in ‘The Ultimate Encyclopedia Of Science Fiction’ (1997, Carlton Books) edited by David Pringle, Disch proved himself to be ‘a deep well of many waters.’

THOMAS M DISCH

2 February 1940 – 4 July 2008

1962 – “The Double-Timer” (‘Fantastic Stories Of Imagination’, Vol.11 no.10, October 1962), collected into ‘Fundamental Disch’ (Bantam Books, 1980).

1963 – “The Demi-Urge” (‘Amazing Stories’, Vol.37 no.6, June 1963).

1963 – “Final Audit” (‘Fantastic Stories Of Imagination’, Vol.12 no.7, July 1963).

1963 – “Utopia? Never!” (‘Amazing Stories’ Vol.37 no.8, August 1963) edited by Cele Goldsmith.

1964 – “Minnesota Gothic” as by ‘Dobbin Thorpe’ (‘Fantastic Stories Of Imagination’, Vol.13 no.1, January 1964), with artwork by Lutjens. Plus short story “A Thesis On Social Forms And Social Controls In The USA” as by Thomas M Disch.

1964 – “Death Before Dishonour” as by ‘Dobbin Thorpe’ (‘Fantastic Stories Of Imagination’, Vol.13 no.2, February 1964) also edited by Cele Goldsmith.

1964 – “Now Is Forever” as by ‘Dobbin Thorpe’ (‘Amazing Stories’ Vol.38 no.3, March 1964) with Virgil Finlay artwork.

1964 – “Genetic Coda” (‘Fantastic Stories Of Imagination’, Vol.13 no.6, June 1964).

1964 – “Descending” (‘Fantastic Stories Of Imagination’, Vol.13 no.7, July 1964), collected into Judith Merril’s ‘Tenth Annual Edition: The Year’s Best SF’.

1964 – “Nada” (‘The Magazine Of Fantasy & Science Fiction’, No.159, August 1964) collected into the fourteenth ‘Best From Fantasy & Science Fiction’ anthology.

1964 – “Dangerous Flags” (‘Fantastic Stories Of Imagination’, Vol.13 no.8, August 1964).

1965 – ‘THE GENOCIDES’ (US)

1965 – “102 H-Bombs” (‘Fantastic Stories Of Imagination’ Vol.14 no.3’).

1965 – “White Fang Goes Dingo” (‘If’ no.89, April 1965) novelette later expanded into ‘Mankind Under The Leash’.

1966 – “The Roaches” (‘SF Impulse no.9’, November 1966), plain Marcia Kenwell moves from Minnesota to find her own way in Manhattan but finds only ‘dull jobs at mediocre wages’ and cheap apartments with dread cockroaches she battles against. But when the insanitary Shchapoli trio move into the next room, she discovers she can will the bugs to obey her, and uses them to drive the three out. She is now mistress of every cockroach in the city. This story is advertised on the ‘In Our Next Issue’ page 159 of ‘SF Impulse no.8’

1966 – ‘MANKIND UNDER THE LEASH’ (US), ‘humiliations render people into pets’ (‘The Ultimate Encyclopedia Of Science Fiction’, 1997, Carlton Books). Also known as ‘The Puppies Of Terra’. Humankind is enslaved by aliens, who like our looks and the way we dance, until the hero – a wimp with brains, decides to drive away the new masters by annoying them, the way a dog might annoy its owner. They eventually leave because ‘they couldn’t stand the barking.’

1966 – ‘THE HOUSE THAT FEAR BUILT’ (Paperback Library) collaboration with John Sladek as by ‘Cassandra Knye’.

1966 – ‘ONE HUNDRED AND TWO H-BOMBS’ (UK, Compact) short story collection, later revised as ‘White Fang Goes Dingo And Other Funny SF Stories’.

1966 – “Three Points On The Demographic Curve” (‘SF Impulse no.10’, December 1966), vast time-spanning mini-epic ‘in a tone of wry humour’, in a ‘Make Room Make Room’ Malthus-overcrowded 2440, Investigator Darien Milkthirst tracks down mass child kidnappings to Prosper Ashfield – Last Man On Earth, from the future, who is trying to repopulate a lifeless Earth. When the stolen children lack motivation he sells them to Elijah Grasp in 1790 as factory child-labour, kicking off the Industrial Revolution. As his robots work, Ashfield places himself in stasis until the solar system’s bleak end. Plus ‘Hell Revisited’ Disch’s interview with Kingsley Amis, six years after the publication of ‘New Maps Of Hell’, Amis expresses his disappointment with the subsequent work of Pohl, Bradbury, Sheckley, Clarke and Blish. ‘Perhaps it’s the curse of ambitious science fiction that it goes outside the field of science fiction altogether and becomes something pretentious, fantastic and certainly obscure.’

1967 – Brian Aldiss reviews ‘The Genocides’ in ‘SF Impulse no.11’ (January 1967), ‘a new writer has come along, to delight us with an unadulterated shot of pure bracing gloom.’

1967 – “The Number You Have Reached” (‘SF Impulse no.12’, February 1967, with Keith Roberts art), astronaut Justin Holt returns from Mars to find he’s ‘the last man on earth’ in a winter city after neutron bomb war, everyone is dead although buildings remain intact, with bodies automatically removed by cleansing, except a woman keeps phoning him. Is she real? Or will admitting her reality be to accept his own madness? Keith Roberts editorial calls the story ‘a suave and polished account of a man’s obsessive fantasy. Or is it fantasy? One is never quite sure; and Thomas M Disch is far too skilled a writer to give too much away.’

1967 – ‘ECHO ROUND HIS BONES’ (US) an unexpected ‘echo effect’ produced by matter transmission, delves into the shadow existence of artificial, accidental doppelgangers.

1967 – “The Affluence Of Edwin Lollard” (‘New Writings In SF no.10’, Dobson Books 1967, Corgi Paperback) edited by John Carnell, the consumer-satire of a man charged with ‘criminal poverty’, quoting George Bernard Shaw as source.

1968 – ‘CAMP CONCENTRATION’ (US), a wicked book, one of ‘The Peaks Of Disch’s SF Career’, and a ‘New Wave bombshell’, intelligence in selected prisoners in a military Concentration Camp is temporarily enhanced, at the eventual cost of their lives, the diary of a character who is locked up and given a drug to heighten his intelligence; an unfortunate side-effect of the drug is that it induces death within a matter of months.’ To ‘Science Fiction: The Illustrated Encyclopedia’ (1995, Dorling Kindersley) edited by John Clute, ‘the analogy with syphilis is explicit – syphilis has very often been (wrongly) treated by writers as a disease that first inspires, then kills.’

1968 – ‘BLACK ALICE’ (US, Doubleday) a contemporary mystery-suspense novel written jointly with John T Sladek as ‘Thom Demijohn’. The UK cover-blurb on the Panther edition is ‘Heiresses aren’t usually found in whorehouses. That was the beauty of the plan.’

1968 – ‘UNDER COMPULSION’ (UK) short story collection.

1969 – ‘THE PRISONER’ (US, Ace), novelisation of the cult Patrick McGoohan TV series, aka ‘The Prisoner: I Am Not A Number’.

1971 – “Angouleme” (‘New Worlds no.1’, Sphere paperback edition) ‘The Science Fiction Quarterly’ edited by Michael Moorcock, art by ‘Glyn Jones’. Densely-written highly imagist story that approaches prose-poetry in its intensity. Angouleme is the name given to New York harbour by Florentine-born navigator Giovanni Verrazzano in April 1524. Samuel Delany devotes his critical work ‘The American Shore’ subtitled ‘Meditations On A Tale Of Science Fiction By Thomas M Disch: Angouleme’ to his analysis of this story. Pre-teen Alexandrians led by Little Mister Kissy Lips, with Sniffles, MaryJane, Celeste DiCecca and Amparo (of course) gather by the Verrazzano statue to debate and discuss who they should murder, deliberately referencing Raskolnikov from Dostoevsky’s ‘Crime & Punishment’ (as Raskalnikov). There are other arty references as they dance to Terry Riley’s day-long ‘Orfeo’. As others fall away there is only Little Mister Kissy Lips who follows homeless Alyona Ivanovna with his father’s French duelling pistol, and faces him. Does he shoot him? The ending is ambiguous. Whether this story can even he classified as SF is equally ambiguous.

1971 – “Feathers From The Wings Of An Angel” (‘New Worlds no.2’, Sphere paperback edition) edited by Michael Moorcock, art by Claire Murrell. An experiment in overwrought melodrama, an exercise in Victorian sentimentality, a blind girl child, a dying mother, and Tom Wilson a man of ‘careworn aspect’. Through what seems an act of divine intervention his life-story wins a $10,000 ‘Life Magazine’ competition, which arrives too late to save the mother. ‘It cannot be that the earth is man’s only abiding place! It cannot be that our life is a mere bubble cast up by eternity to float a moment on its waves and then sink back into nothingness!’

1971 – ‘WHITE FANG GOES DINGO AND OTHER’ (UK, Arrow) short story collection, with the novelette magazine origins of ‘Mankind Under The Leash’, reconfigured collection from ‘102 H-Bombs’.

1972 – “The Wonderful World Of Griswald Tractors” (‘New Worlds no.3’, Sphere paperback edition) edited by Michael Moorcock. Absurdist compressed four-page novel of wild invention. Chiropractor and dabbler in hypnosis Selbst has guillotined himself, or was he murdered? The Society for the Legalization of Death becomes a successful business specialising in exotic suicides and games of chance. Hired thugs (Puerto Ricans) set Colin against his father Nathan in gladiatorial contest, as Brooklyn burns. They escape by Staten Island ferry to ghostly abandoned suburb on Long Island.

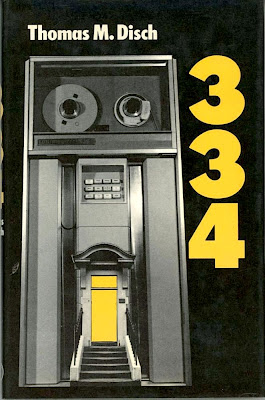

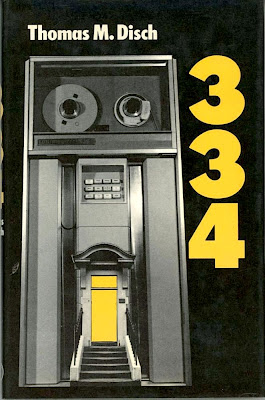

1972 – “334” (‘New Worlds no.4’, Sphere paperback edition) edited by Michael Moorcock, art by RG Jones. Running from p.58 to p.155 in Six Parts divided into forty-three sequences dated from ‘The Teevee’ (2021) to Mrs Hanson In Room 7 (2026), Amparo from ‘Angouleme’ joined by a new cast of odd characters.

1972 – ‘334’ (UK, MacGibbon & Kee), a completely linked set of vignettes depicting an oppressive view of a dying culture in an over-populated future. There is no hero. M John Harrison reviews it in ‘New Worlds 6’, pointing out that excerpts had already appeared in NWQ, ‘the novel presents a detailed picture of a New York in the near future, describing the lives and ambitions of a group of people’ living in a vast and decaying apartment building (334 East 11th Street)… ‘if ‘334’ hadn’t been published as SF Disch would have been in line for the Booker Prize at very least and would certainly have received the serious critical attention his work must eventually get. Perhaps he is wasting his time working within the terms of SF’? The address, when written 3-3-4, represents an arithmetical pattern that governs characters, sequences and geography. The novel lives and breathes its author’s love-hate understanding with New York.

1973 – “The Assassination Of The Mayor” (‘New Worlds no.5’, Sphere paperback edition) edited by Michael Moorcock. Twenty-two line poem written in the same compressed-novel style as his recent fiction, ‘dreadful garbage trucks that grew louder every day…’

1973 – ‘GETTING INTO DEATH: THE BEST SHORT STORIES OF THOMAS M DISCH’ (UK)

1973 – ‘THE RUINS OF EARTH’ (UK) anthology edited by Thomas M Disch, reviewed in ‘New Worlds 6’ by M John Harrison, who says ‘the theme of the book is The Environment and what it does to us, what we do to it… Disch is an editor with exceptional intelligence and taste… and has combined SF and non-SF to make a particularly coherent statement on the theme.’

1974 – “Pyramids For Minnesota” (‘Harper’s Magazine’ January 1974), later included in the Disch-edited ‘The New Improved Sun’ (Harper & Row, September 1975).

1974 – ‘BAD MOON RISING’ (UK) anthology edited by Thomas M Disch.

1974 – “The Santa Claus Compromise” (‘Crawdaddy’, December 1974), selected by editors Brian Aldiss & Harry Harrison for ‘The Year’s Best Science Fiction no.9’ (Futura, 1976).

1975 – “The Apartment Next To The War” (‘Science Fiction Monthly’, Vol.2 no.6, June 1975).

1975 – ‘CLARA REEVE’ (Knopf) an enormously complicated Gothic tale, published as by ‘Leonie Hargrave’.

1975 – “At The Pleasure Centre” (‘Science Fiction Monthly’, Vol.2 no.11, November 1975), New English Library colour tabloid edited by Julie Davis.

1976 – “The Black Cat” (‘Shenandoah’, Summer 1976), later collected into ‘The Man Who Had No Idea’.

1976 – “The Eternal Invalid: A Celebration Of Life With The Author Of Rash” (‘New Worlds no.10’) Corgi anthology edition edited by Hilary Bailey, a spoof interview with the morbid GG Allbard on his sickbed at his Ealing flat, 13 March 1975, ‘within five minutes I was having a bowel movement in rhymed couplets!’, the interviewer is seldom allowed space to speak, as he talks of ‘a literature of extremity’ in which ‘hospitals are the cathedrals of the twentieth century.’

1977 – “How To Fly” (‘Bananas’, Summer 1977), later collected into ‘The Man Who Had No Idea’.

1977 – “Planet Of The Rapes” (‘Penthouse’, Vol.12 no.9), published in the UK edition of ‘Penthouse’, later collected into ‘The Shape Of Sex To Come’ edited by Douglas Hill (Pan Books, 1978).

1978 – “Concepts” (‘The Magazine Of Fantasy & SF’ no.331, December 1978), edited by Edward L Ferman, novelette later collected into ‘The Man Who Had No Idea’.

1979 – ‘ON WINGS OF SONG’ (Gollancz), set in a New York on the brink of disintegration, the central character longs for success in opera, his eventual triumph is deeply ambiguous. The ‘Science Fiction: The Illustrated Encyclopedia’ (1995, Dorling Kindersley) suggests ‘in this novel, Disch may have been making a veiled statement about his own SF career; since its publication, he has concentrated in other genres.’

1980 – ‘WHO WRITES SCIENCE FICTION?’ by Charles Platt (Savoy Books, 1980), ‘An Amazing Journey Into The Minds Of Thirty Top Science Fiction Writers’, Platt interviews Disch in his eleventh-floor apartment in a sixteen-storey ex-office building in New York’s Chelsea area close by Union Square, ‘a writer who is known in the science-fiction field for his almost elitist, civilized sensibilities.’

1980 – “The Vengeance Of Hera Or, Monogamy Triumphant” short story in anthology ‘Edges’ (Pocket Books, November 1980) edited by Virginia Kidd & Ursula K LeGuin, later collected into ‘The Man Who Had No Idea’.

1982 – “Cantata ’82: An Ode To The Death Of Philip K Dick” (‘Interzone no.2’, Summer, June 1982) poem by Thomas M Disch.

1982 – review of Thomas M Disch’s collection ‘The Man Who Had No Idea’ (Gollancz, April 1982) in ‘Interzone no.3’, Autumn, September 1982, originally published as a short story in ‘The Magazine Of Fantasy & SF’ (no.329, October 1978), in a world where licenses are required in order to participate in conversations, Barry Riordan risks failing his exam because he cannot think of anything original.

1984 – “Canned Goods” (‘Interzone no.9’, Autumn 1984), an ‘all-star’ line-up, after an unspecified economic crash Mr Weyman barters artwork with art-dealer Shroder – for food, Motherwell is devalued, with a brief gag about trading Warhol for a can of Campbell’s Tomato Soup.

1986 – “Hard Work Or, The Secrets Of Success” (‘Interzone no.17’, Autumn 1986).

1988 – Gregory Feeley interviews Thomas M Disch in ‘Interzone no.24’ (Summer 1988).

1988 – “The Village Alien” (‘Interzone no.25’, September/October 1988), reprinted from ‘The Nation’, Disch investigates the ‘True Story’ of real-life author Whitley Strieber’s ‘Communion: Encounters With The Unknown’, superficially convinced of his claims of alien abduction and anal-probe, even though it was expanded from short-story “Pain” (published in Dennis Etchison’s anthology ‘Cutting Edge’, 1986). There’s an exchange of phone calls, then Disch recounts his own alien abduction via a shrink-blaster into the Frisbee-sized saucer of the alien Winipi who warn him of Xlom money-making plans to take control of Earth, and that Strieber has already been transformed!

1990 – “Celebrity Love” (‘Interzone no.35’, May 1990) Thomas M Disch short story.

1992 – Book review of Thomas M Disch (‘The M.D.’) (in ‘Interzone no.60’, June 1992). A horror fantasy that unflinchingly plumbs the dark underside of the human condition, it features a doctor given a magic staff (or caduceus) by the Devil, he makes a terrifying mess of the wishes granted him by this tool. To ‘Science Fiction: The Illustrated Encyclopedia’ (1995, Dorling Kindersley) edited by John Clute ‘it is a harsh message, but a necessary lesson: Disch’s entire career, in a nutshell.’

1994 – “The Man Who Read A Book” (‘Interzone no.87’, September 1994), barely a whisper of SF, more a cynical humorous spoof on the declining book trade. People don’t read books anymore, instead they devise devious scams to make money out of naïveté. Responding to an ad for publisher’s readers Jerome Bagley reviews ‘A Collector’s Guide To Plastic Purses’, then meets aspirant novelist Lucius Swindling and agrees to read his manuscript ‘The Last Of The Leather Stockings’, plagiarizes it into ‘I Iced Madame Bovary’ in order to get various Literary Grants.

%20Fossils%20In%20Stone.jpg)

%20Stone%20Fossils.jpg)

%20playing.png)

.png)