‘FIERY RAIN AND RUBIES,

COOLING SUN…’

Album Review of:

‘NO OTHER (DELUXE EDITION)’

by GENE CLARK

(4AD 0070 CDX) www.4ad.com

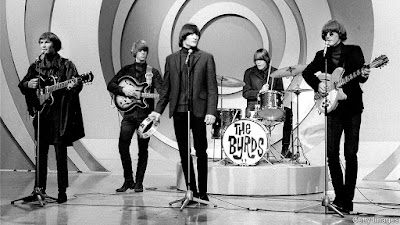

Those perceptive enough to catch the exquisite ‘The Byrd Who Flew Alone’ on BBC-4 TV, will know the complex story and provenance of this mythically flawed great lost album. First released in Spring 1974, and already remastered in an Expanded 2003 Asylum reissue, this beautiful 2CD package adds a further two tracks – session-outtakes of “The True One” and a contrasting take on the majestic rococo “Strength Of Strings”, with a learned new Johnny Rogan essay, a studio photo gallery and John Einarson musician notes to create the definitive edition. Despite star sidemen Russ Kunkel (of The Section) and Joe Lala (of Blues Image) on drums, Jesse Ed Davis and Danny Kortchmar on guitars, and the Ventures Jerry McGhee on “Lady Of The North” (written with Doug Dillard), it’s never less than Gene Clark’s album. Here, he’s perfectly at ease working with seasoned technically-slick LA musicians who are exactly attuned and in sympathy with Gene’s aspirations. And it’s a mature work, no more striving through the tyro Byrds Dylan-Beatlesist prism, but with a deeper appeal not always quite so immediate, yielding more to repeated plays. And oh, to have been at those sessions and seen those tracks evolving from songwriter demos through their production stages, through the relegated studio-takes into the final full album. At least we now have some aural glimpses. To misquote Gene himself, ‘our ears are hearing twice.’

The opening track “Life Greatest Fool” was issued as the album’s second single in March 1975, with Michael Utley’s keyboard taking a classic Floyd Cramer piano-styling, while Ben Keith’s uncredited dobro adds curling steel guitar to its country-loser weariness. Just the correct side of the Maudlin County Line, the Gospel back-up voices are missing from the 30 April alternate take, leaving the catchy jog-along rhythm more starkly contrasting around its ‘stoned numb and drifting’ lyric. Soaring into the rising acoustic swell of the sharply visionary “Silver Raven”, ‘have you seen the old world dying, which was once what new world’s seem.’ At 4:54-minutes, the outtake rips it apart only to reassemble it into an extended 6:35-minutes of a more murky electric gravity that Sid Griffin’s song-notes term ‘Dr John funk’. Gene’s voice slurs ‘the changing windows’ line and lifts into near falsetto as the raven’s wings ‘they barely gleam’ and the ‘sea begins to cry.’ The long fade resolves into a choppy soul stew. Sly Stone is said to have dropped in on the sessions. If so, his influence ghost-permeates the groove. Just as Gene was said to be in awe of Stevie Wonder’s densely-textured ‘Innervisions’ (August 1973), he works and reworks material with perfectionist producer Thomas Jefferson Kaye, beyond what would otherwise be considered entirely acceptable, towards higher and yet-higher planes of expression, with scant regard for budgetary restrictions.

The title-track, spun-off as the album’s first single in January 1975, opens with lightly-deployed sprinkles of percussion and guitar, building with supporting back-up harmonies. It seems to be a lyrical argument against the ‘Lord is love’ – in favour of the more humanist ‘all alone we must be part of one another,’ with only ‘the pilot of the mind’ to determine our true course. Although Gene provides a more convoluted explanation, involving untraceable signals from an alien outer-space intruder. There are electric keyboard shimmers leading into the 8 April outtake, with scat vocals seemingly improvised over the lengthy shuffling rhythm interplay play-out, and a false close that rebuilds effectively. Then another stand-out track, “Strength Of Strings” with glistening ascending sweeps that ‘roll on winds, with swirling wings.’ A pause. A resumption, transcendental in its soaring eulogy to the soul-soothing power of music, rephrasing what Albert Ayler had already termed ‘the healing force of the universe.’ The heavier, slightly less ethereal 15 May outtake, with acoustic guitar break, remains as breathtakingly moving.

Chris Hillman’s mandolin features on “From A Silver Phial”, following a surging piano play-in, with striding stirring guitar solos, and Gene’s most elaborate metaphorical imagery since “Echoes”, in sense, and evocative abstract non-sense poetry, each alliterative mystical syllable speaks in an impressionistic sonic sorcery of ‘the sword of sorrow sunken in the sands of searching souls.’ Its literal meaning is anyone’s guess. The 25 April alternate take is more acoustic, with the emotive vocal mixed even more clearly to the fore. At eight-minutes, “Some Misunderstanding” has the weary acoustic yearning of Dylan’s “I Shall Be Released”, from its strummed country opening to the aching guitar solo and end-sequence. Gene’s broken voice struggles to articulate how ‘we all have soul’ but ‘nobody knows just how much it takes… to’ with a three-syllable ‘fly-yi-yi’. ‘We all need a fix, at a time like this, but doesn’t it feel good to stay alive’ delivered with eerie intensity.

For the direct melodic country pacing of “The True One” he assumes the older and wiser role, ‘in the end, the loser is the one who does deceive.’ The simple truths are the ones that matter. As far as regrets are concerned there’s a teasing reference, maybe, to that first Byrds album for which his writer credits resulted in his higher royalty revenue, ‘I used to treat my friends like I was more than a millionaire, spendin’ those big ones like I could afford them.’ A thoughtful David Crosby later recalls how the group were ‘five different people, five very different people’, and how Gene’s sudden affluence provoked an early rift. That the wonder was not that the Byrds broke up when they did, but that they endured for so long. The eighth track, “Lady Of The North” full-circles the album into the redemptive powers of love, its gentle interplay repeating the motif of flight, haunted by the bitter-sweet memory of loss and passing time. Richard Greene’s bluegrass violin saws in around Gene’s baritone intensity. Written for wife Carlie, he selects strong natural organic touchstone key-words ‘seasons’, ‘wind’, ‘mountain’ and ‘ocean’ rooting the imagery firmly in the real. Yet dissolving into an album-closing strangeness of strings.

There’s a bonus slower “Train Leaves Here This Morning”, its strong melody narrating the great American locomotive symbol for movement and new tomorrows beyond open horizons. Already done with light banjo-driven mandolin on Gene’s ‘The Fantastic Expedition Of Dillard And Clark’ (October 1968), and later by its co-writer, Bernie Leadon, taken sweeter and blander for the Eagles megabuck cooing harmonies (on debut LP ‘Eagles’, June 1972). Recorded 29 April, early in the sessions but omitted from the album, this is a gritty stronger interpretation that plays in with moody electric keyboards. If it was intended as a throw-away studio warm-up piece, it shows the level of musicianship operating. And oh, to have been at those sessions.

After uneven periods of substance abuse and uncertainty, this was to be the definitive statement. Restlessly imaginative, songs of hurt, losing and deception, mixed in with the metaphors for flight, it is a stately atmospheric album that hangs melody like paintings in sumptuously rich arrangements. Yet it was commercially doomed by the original Mr Tambourine Man’s tragically self-destructive nature, by its eight-track running time, and by Gene’s refusal to play David Geffen’s promotion games. ‘They say there’s a price you pay for going out too far’ he sings on “The True One”. This is the evidence. If through the course of his career Gene had, and blew so many opportunities through his ornery contrariness, this was his best shot. Yet it was left to subsequent generations of musicians, critics and fans to rediscover and rightly acclaim ‘No Other’.

Published in:

‘RNR Vol.2 Issue.80 March-April’

(UK – March 2020)

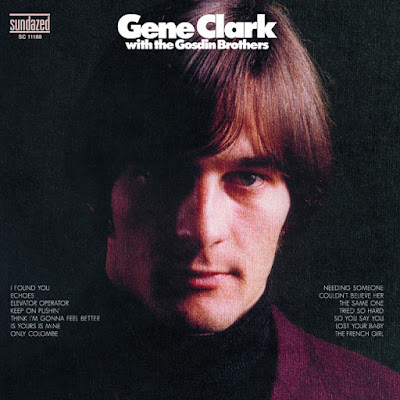

Album Review of:

‘GENE CLARK WITH THE GOSDIN BROTHERS’

by GENE CLARK WITH THE GOSDIN BROTHERS

(Floating World) www.floatingworldrecords.co.uk

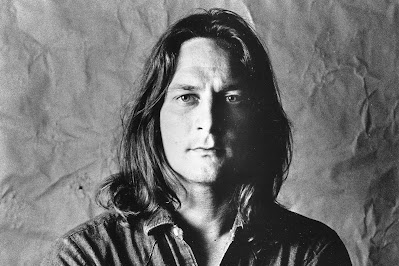

The first Byrds songwriter was not Roger McGuinn, and certainly not David Crosby. Check out the credits on those first three albums and it was Gene Clark’s name attached to “Eight Miles High”, “Feel A Whole Lot Better” and “Set You Free This Time”. He was also the first Byrd to quit, ‘me and my friends got on a plane, one of my friends got off again’ as Croz tells the tale. Gene’s debut solo set from February 1967 has been variously reissued in different forms and mixes ever since, the 1991 Columbia Legacy edition boasting a full twenty tracks, and retitled after the exquisite “Echoes” scored with dancing Leon Russell strings, quite unlike anything else he ever recorded, and worth the price of admission alone. Now returned to its original moody sleeve-photo the album then backtracks to the Beatles-harmonies of “Is Yours Is Mine”, retaining Michael Clarke (drums) and Chris Hillman (bass), before lurching off with Vern and Rex Gosdin onto rusty country trails that the Byrds themselves would eventually follow. There’s a diverse spread of directions across the fourteen tracks, with Doug Dillard’s electric banjo (on “Keep On Pushin’”) and Clarence White’s B-Bender bluegrass guitar. Gene Clark was stubbornly uncompromising, ignoring chart hits and commerce in favour of chasing his own vision. But that vision still shines.

Published in:

‘R’N’R: ROCK ‘N’ REEL’

Vol.2 Issue 76 July-August

(UK – July 2019)

No comments:

Post a Comment