DONOVAN:

THE VIEW FROM

THE BEAT CAFÉ

…

All of a sudden – Donovan Leitch is everywhere. His long-promised

long-awaited

autobiography – ‘The Hurdy-Gurdy Man’ is published

this autumn, in the meantime

EMI are issuing four digitally-remastered

extended editions of previously-USA-only

albums, while he’s launching

a new series of ‘Beat Café’-themed gigs,

with Rat Scabies on drums!

Andrew Darlington is there to get the details…

‘HURDY-GURDY MAN…’

“Histories of ages past, unenlightened shadows cast…”

(‘Hurdy-Gurdy Man’)

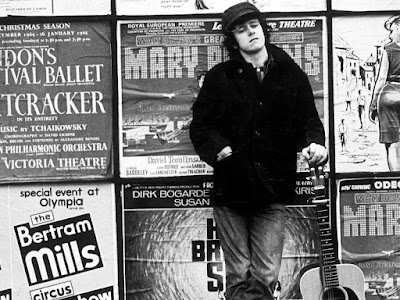

We’re sat in the sun outside a wine-bar some short distance from the venue where he’s due to perform. Donovan will play there tonight in a spiralling crawl of psychedelic lighting, beneath huge monochrome images of three Beat-Generation writers. Jack Kerouac with his deep darkly sensual eyes, an early Allen Ginsberg wearing a striped tie, and the supernatural stare of William Burroughs. There’ll also be a flickering candle stuck in a drained wine-bottle, wax tendrils running. A virtual Beatnik Café. But now – Jason brings us drinks. Red wine for Donovan, ‘thanks, you’re a diamond’. Not the Budweiser I’d specified, sorry – but Coors. ‘It’s American still’ chides Donovan mischievously, ‘wave the flag’. We small-talk, enjoy the vibes. There’s a raggle-taggle minstelstry air – still, about Donovan.

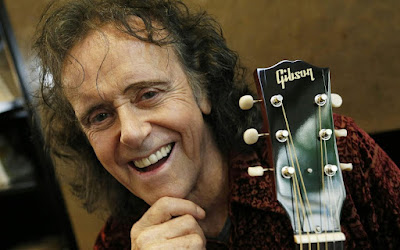

He’d arrived tonight in the ‘City Varieties’ foyer, dressed in black with a ‘Donegal Cruise’ blue plastic bag. His black roll-neck and black jeans betraying their travels, yet he’ll wear the same for the concert. He can also look as worn as his years suggest, until the moments when his face lights up in a spontaneous smile. He has white false-nails on his right hand, all the better to plectrum with. And his hair – thinner, yet reassuringly tousled, up close, betrays a subtle blue tint that makes it appear darker than it is when viewed from audience-seating. He listens attentively to my questions, variants of which he must have been asked very many times before. Then his answers come in unbroken, yet carefully considered streams, addressing each point carefully and thoroughly. Both affected and compelling, relaxed and intense. But it’s obvious that an interview – to Donovan, is an extension of the performance. He is at all times the guru dispensing esoteric wisdoms, just as he, in his turn, had absorbed secret bohemian magics from those who came before him, most obviously those three Beat Poets, but beyond them through mystic and bohemian traditions stretching back, virtually to the misty Celtic dawn of time. ‘And so the journey begins…’ he’ll travelogue on-stage…

But first, now, ‘anyway – you’ve got a list of questions. Don’t let me go on…’

To begin. You’re a similar age to me, although you’re carrying it better. Fifty-nine. Yeh – somebody got it wrong and wrote that I was sixty this year – so I grew a year in just two days! I got a year older in two days! (in fact, to set the record straight, he was born Donovan Phillips Leitch, 10 May 1946)

And you’re in a good place. You’ve been in fashion. And out of it. Now you’re beyond it all, into your own continuum. It’s a good place to be. No commercial pressures. When you want to tour, you know you can sell-out mid-size venues like this with ease. When you put out an album you know it will sell enough to make the exercise artistically satisfying and economically viable. Well this year – yes, I’m in a good position. Why? because I’m returning to the world. I’m ready, ready to present my book – which is called ‘The Hurdy-Gurdy Man’ (2005 Century hardback, 2006 Arrow paperback, ISBN 978-0099487-036) it’s coming out in October on the Century imprint. Yes – I’ve written my autobiography over the years, and now it’s ready. I just came back from Greece last year where I was completing my book with my pal. I did some of it there. Look out for me. There’s also a documentary in the works for next year. And – yes, I’m in a good position. Why? because I’m ready to present my Fortieth Anniversary tour, which is this year and next year. I’m also very pleased with the results of the ‘Beat Café’ album (2004), and its concept is the preface to my show, to illustrate and explore where I came from, and where my contemporaries came from. What I want to do is to re-present my works, alongside the 1960’s bohemian manifesto that me and my brothers and sisters promoted into popular culture. That is – there’s the Beatles, Bob Dylan and Joan Baez, Joni Mitchell and Leonard Cohen, Neil Young, Bert Jansch – and me. And well – the poets, they are the older brothers of the sixties poets. They came before us. The poets are our Big Brothers, our older brothers. I consider Lennon a poet, we all consider Dylan a poet, and if some people don’t see the poetry in my songs… well, they got plugs in their ears. And actually, all Twentieth Century movements come out of the Bohemian Cafes – from Modern Art, Socialism, Spiritualism, to Dance, theatre and movie-makers. The cafes of the twentieth-century produced the artists and the thinkers who move society on. This is how it works. And so October kicks off my Fortieth Anniversary. I initially intended to tour the UK first, then the UK grew and grew and grew, and I thought ‘that’s good’, and I tried to stretch into Europe, and I tried to stretch into Dublin – and couldn’t make it. So, as part of this tour, I’m saving Glasgow, Edinburgh, and London, saving them for the anniversary presentation in October. And I’m missing Dublin this tour. So I hope to bring the ‘Beat Café’ to Ireland, some time soon.

On your ‘Beat Café’ album you do a version of the traditional song “The Cuckoo”. Kristen Hirsh – formerly of Throwing Muses, also recorded a version of the same song (on her ‘Hips & Makers’ album, 1993), but she described it to me as ‘an Appalachian Folk Song’. Did he really (sic)? Is that right? It’s an old tune. And it’s a favourite, a favourite song of mine. “The Cuckoo” is probably an Irish song that went over with the migrants. ‘Ah-diddlie, Ah-diddlie, A diddile-diddle-dah’ (he sings, emphasising its lilting melancholy). It’s an old way of singing – ‘keening’, you know? Which means it’s Celtic. Probably even pre-Celtic. Folk Songs have a way of diversifying. Folk Songs are amazing. A Folk Song can last just as long as an archaeological find. They are actually the repositories of the history of humankind, the human spirit. There are certain tunes that carry a ritual, or a circular dance that goes back millennia. And I know them. I feel them in my heart (he clutches his hand over his chest). There are five vowel-sounds – AE-Ah-OU. Although the Greeks say there are seven-to-nine vowels. But (sings) ‘a-eee-ah-owe-you’, all these root-sounds are in every language, no matter where or when. So you don’t have to understand the language to understand its particular soulful sound. ‘Cos when a local singer, whether Flamenco, or East Indian, or Native American, or an Eskimo... or a troubadour from Scotland – me!, what do you hear? When you hear the music, and it touches you – listen to the vowel-sounds (sings) ‘ah-ah-ah-ah-o-luuuuve-yu-o-oo’. It’s the vowel-sounds that are creating the emotional contact with people. And when I discovered this secret of World Music, I realised it was really very simple. When I studied it I realised it was to do with the Chakras. There are seven centres on the spine that the yoga-schools speak of. And those seven centres respond and resonate like strings on a guitar. And the masters of the art of music naturally and consciously – or maybe unconsciously, can make pieces of music that touch millions of people because they’re playing ‘their Chakras’. A Universal Language? Yes. They’re actually playing the universal language, it’s amazing isn’t it?

On the ‘Beat Café’ album you utilise the genius of excellent double-bass-player Danny Thomson (who also recorded “The Cuckoo” as part of Pentangle on their fine 1969 ‘Basket Of Light’ album). His presence represents the continuation of a long-term association, because Danny accompanied you on “There Is A Mountain” (a UK no.8 hit single in November 1967), and the ‘Donovan In Concert’ album (September 1968), and he’s also part of your Open Road group of the early-70’s. But he’s not with you on this tour. No – the problem is… I couldn’t get Danny. Danny was booked to do other things. And anyway, the purpose of the ‘Beat Café’ is to teach the young. So we put together a young band (including ex-Damned Rat Scabies on drums, who has his own ‘Holy Grail’ literary effort to promote!). The ‘Beat Café’ is an exploration of Bohemian influences on popular culture. And when you listen to the album, you hear the jazz influences, the Blues influences, the Folk influences, the spiritual chants, and the importance of poetry in popular culture. If it wasn’t for the three Beat Poets – (Jack) Kerouac, (Allen) Ginsberg, and (William) Burroughs, the doors wouldn’t have been opened. If it wasn’t for those three Beat Poets the doors wouldn’t have been opened for the singer-songwriters of the sixties to come in. Dylan follows Kerouac. But Dylan Thomas also broke down barriers as well. And I follow Dylan – Thomas, and W.B Yeats (1865–1939). So the word is important. It’s back to the word. Who are the manipulators of language? Poets. What are the key-sounds of emotion? The five vowel-sounds. Why has poetry been separated from music? On purpose. Because they knew that poetry and music moves the people. If the poets have the ritual again in their own control, it’s like the Shamans of the tribes. So the Governments who want to control the people separate music from poetry. That’s the first thing they have to do. And to that end they killed probably sixteen-million witches between the twelfth and the fifteenth century. The reason? The Church killed the witches ‘cos they were trying to kill the rituals. Once again – separating the cult from the people. Separating the ritual of the year. ‘Cos all these witches were just herbalists, they were doctors, they were mid-wives, they were the magic people of the local community. If someone was ill, you went to see them. And of course, they didn’t like that. Because medicine was becoming powerful, and universities were being opened – and ha-ha-ha – all that stuff, I know. But my ‘Beat Café’ explores a much more fundamental thing – the way the music and the poetry came together again, and informed the sixties.

You actually perform a Dylan Thomas poem on ‘Beat Café’ (“Do Not Go Gentle”). I do the Dylan Thomas poem ‘cos he was saying a painful goodbye to his father, telling his father not to go gentle into that good night. ‘Rage’ against the dying of the light. Don’t take it (laughs) lying down – it sounds like a pun! Don’t take death lying down? – stand up and be proud! He didn’t mean scream and shout. He just meant, be strong – you know? Don’t give yourself up to the other world. Know that you’re passing into it having had a great life. And because my father also passed five years ago, I recorded that…

You’ve also recorded a Yeats poem – “The Song Of The Wandering Aengus” on your ‘HMS Donovan’ album (July 1971) – ‘and pluck till time and times are done/ the silver apples of the moon/ the golden apples of the sun’. But even earlier than that you recorded one of your own poems – “Atlantis”, which became an American Top.10 hit single (US no.7 in May 1969). “Atlantis” was kind-of a prose poem, I suppose. More of a kind of declamation. Yeah, like a prose-poem. Most of my poems are rhymed, ‘cos my father taught me how to listen to poetry. Donald was his name. He was a self-taught, well-read man. And he read – didn’t he just!, he read poetry again and again. And from the age of two he read to me constantly. He read me everything. Celtic visions. And visionary poetry. In fact – it was my daily bread-&-butter. I just took it in my stride. I didn’t think listening to great poems was anything different from going to see cartoons. And so reading my “Atlantis” piece, was very natural for me. Because my father used to get up and read to the family.

‘THE BARD OF BOHEMIA’

‘On a windy Saturday, St Albans market day

little did I

know the work I was to do, or the love I had to show…’

(“There Was A Time I Thought”)

I understand the Beat Poet influences, and appreciate the effect Woody Guthrie must have had on you. But like me, you were entering your teens in the late 1950’s. And I’m sure I over-heard you jamming a little Chuck Berry during the soundcheck. Didn’t you ever have an Eddie Cochran phase? Weren’t you watching the ‘Oh Boy’ TV-show as a kid? I had a phase of Rock ‘n’ Roll. I was an adolescent boy. Buddy Holly was my idol when I was twelve. But no – in the beginning it was Folk music, even though they didn’t call it Folk music. I lived in Glasgow (the Maryhill district), although there was more Irish in my family than Scots. So I just heard nothing but songs all the time. Somebody would put a chair in the middle of the room, and sing their song. That happened at parties, birthdays, funerals, weddings, births – somebody would go into the middle of the room, and there would always be songs. And then when I was ten we moved down to England. My father moved us down as part of the mid-fifties migrations. People were leaving the industrial cities and coming down to the New Towns around London. So my Dad moved us into Hatfield, and that’s when I heard Buddy Holly and I went – ‘aaah, this is incredible!’ It didn’t make me want to form a Rock ‘n’ Roll band or anything like that because I very swiftly went into Further Education College… (Donovan is distracted by a newcomer) Hi Ian, I’m doing a little interview, but please join the company… have you got a fag there boy? – one cigarette a day me, here we go!... sorry…

(I attempt to refocus Donovan back to the interview) I can see the attraction Buddy Holly must have had, from the lyrical point of view. Buddy Holly breathed his lyrics, y’know – (sings) ‘Listen to me-ee, hear what I sa-ay…’ (‘have you heard Buddy Holly?’ to Susan, also sitting decorously at our table) ‘…listen closely to me-ee-hee’ and so – ‘ah-ah-ah’ (the Donovan vibrato in a Buddy Holly-style). So when you hear Donovan going (breathily) ‘aah-haa-haaa’, I guess it’s a Buddy Holly influence. And Buddy also – I didn’t know till later, he produced his own work, recorded his own work, wrote his own work, performed his own work. So this is like… this is a Renaissance Man. This is a man of all parts, whereas most singers of the time were being discovered by a producer, dressed up by a manager, given a haircut by an agent and put on the road. But Elvis and Buddy Holly and Eddie Cochran, they refused to do that. And the Everly Brothers, they came from Irish Granny’s – did you know?, and they listened to lots of Irish Folk Music when they were kids. And so – Buddy Holly was a great influence, but then I went to Further Education College and immediately met Bohemia and I said ‘this is where I belong. This is bohemia. The girls look better. The guys dress better. There’s art, there’s poetry, and the music is better.’ In the school I’d been to – a Secondary Modern School, the only instruments they had were a recorder and a tambourine. And y’know – once a month, they had us bang the tambourine and try to blow the whistle. They called it a music lesson! They had no idea about what they were trying to do. So when I went to Further Education College the world of art lay before me. And that’s when I first heard Woody Guthrie and Miles Davis, Charlie Parker, Joan Baez and Pete Seeger. Also – in the college, I saw Folk Singers, of course. But after that I wanted to go on to Art School, ‘cos a couple of my pals were going on to Art School, but for that you actually needed passes. You had to have five ‘O’-levels, and that meant you had to study Physics or Geography, history, or biology – and what would I need those for? History I already knew. I loved it. I could do that. Biology? – I was quite interested in young girls by then, so biology was an interesting subject to me. But the others? A couple of pals were getting in for free – y’know? getting in on lots of drawings. Getting the grant with lots of paintings. I didn’t have a lot of paintings or a lot of drawings. And then I met Gypsy Dave (long-time friend and collaborator). Gypsy wasn’t in the college, but he said… he looked at me and he said ‘it’s bullshit isn’t it? it’s absolute bullshit’. And I said ‘yeah, everything’. And he said ‘yeah, EVERYTHING’. And I said ‘yeah, even going on to Art School’. So halfway through the Further Education course I went ‘I can’t do this!’ Years later my pals who’d gone on to Art School said, they were so glad for me that I didn’t go. I said ‘why?’ They said well, we had to learn all this stuff for four years, and then after we left we had to un-learn it all, get rid of it, because they’d taught us about so much stuff we forgot who we were in it all. And that was the story. And anyway, there’s only two painters making any money, Peter Blake and David Hockney. And it looked like they were going to clean up. Like Andy Warhol in the States. But I think I only wanted to go there – to the Arts School, because of the music anyway. So instead we started going to the Art School Balls – ha-ha-ha (a sly Leslie Philips laugh), and they would say, ‘well, let’s get a few guitars together’. Because at that time, all over the country people were picking up guitars and they ended up being the Rolling Stones, the Yardbirds, the Kinks, the Who, the Hollies, the Zombies, the Animals – ha-ha-ha. Not all of them went to Art School – but, they were hanging out at Art School. At the Art School Balls. Then I realised there was a Coffee House, a Jazz Club, a Folk Club, and an Art School in most of the old towns – and the old town for me was St Albans. That was my manor. Living in Hatfield, hanging out in St Albans. Which, of course, is a Roman city, with a thousand-year-old Cathedral. And I used to hang out in the graveyard – we’d sleep there, and then we’d get chased on by the Police, while I was learning guitar from Dirty Hugh. In my book you’ll read about Dirty Hugh. He was a tall good-looking man with long hair, a long beard and a long coat, a really interesting guy. But he never bathed. He was a beautiful-looking man, more beautiful than Rasputin, but … I don’t know, sort-of like those ideas of wizards, y’know, not the ones with the hat-with-the-stars-on-it and the cloak. But the REAL wizards. And he played fascinating guitar styles that I wanted to learn. So I spent three days with him, and he stank to the high heavens. But one must suffer for one’s art mustn’t one? We used to sleep in the graveyard, then get up the next day, and he’d show me the next pattern. Patterns which I learned were called the ‘claw-hammer’. A style invented by the Carter Family in 1928 by transposing banjo-styles onto guitar. Just as Segovia had saved the guitar for the whole century by transposing Bach from organ to guitar. He saved the guitar for the century – the whole twentieth-century. And Ma Carter saved guitar in another way by developing those finger-styles. And I learned it. And Dirty Hugh taught me. Until 42 years later (slow and calculated… 19 November 2003, the University of Hertfordshire), I’m in that same Cathedral being given the cap-&-gown, the honorary Doctor of Letters for my work, for my poetry which honours the planet, and for my work supporting ecology as well. I was there with 200 young students, and with a few other older faces, taking the cap-&-gown and the scroll, while outside were the same gravestones, where I’d slept and been chased on by the Police 42-years earlier! It was a great honour. And it’s an honour which I much value over the ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall Of Fame’ or the Ivor Novello award that I got for my first song, which is like an Oscar for song-writing. I value the Doctor of Letters because of my father, only he was not alive anymore. I wished he’d been there. Neither was my mother. But my family was there in the great cathedral of St Albans. My family were there.

I saw you recently at the Manchester ‘Bridgewater Hall’ when you were celebrating the discovery and final release of your earliest-ever demos, as your ‘1964’ album. Following those demos you made two albums in one year – 1965, ‘What’s Bin Did And What’s Bin Hid’ (June) and ‘Fairy Tale’ (November) the second one, amazingly, an evolution on the first. The track “Sunny Goodge Street” demonstrating an impressive sophistication with a jazz-sensitivity recognisably there on ‘Beat Café’. And you were nineteen! Today I saw you sound-checking with “Ballad Of Geraldine” also from ‘Fairy Tale’. It uses the same tune as Bob Dylan’s “Girl From The North Country” – but in fact both songs lift from Dominic Behan’s ‘Patriot Game’, and probably traditional sources beyond that. It’s about a young, single and pregnant girl. The father of her child (‘a groover called Mick’) doesn’t know yet. She’s hoping he’ll stay. Fearing he won’t. Yep. I’m gonna do ‘Geraldine’. ‘Geraldine’ is part of the café. In “Ballad Of Geraldine” and “Young Girl Blues” you are writing through female personae, writing with sensitivity from a female point of view ‘you are just a young girl/ working your way through the phonies…/ yourself you touch, but not too much/ you hear it’s degrading’ – a third person short story approach that no-one else – not even Dylan, has attempted. They show a degree of sensitivity unusual even now in these confessional self-authenticating times. Yes – “Young Girl Blues”. I’ll tell you what that is, it’s part of the poet’s studies. In ancient Celtic times the poet studied twenty-one years, in periods of seven, and the first seven were ‘Occasional’ verses to learn how to write for weddings, love songs, funerals… occasions, ritual songs, agricultural songs. A true poet can write in any form, and must learn how to write from all points of view. And so writing from the point of view of ‘Geraldine’ – it’s a rediscovery of that. I didn’t know I’d done it at first, and people said ‘but you’re singing like you are Geraldine’, and I said ‘yes, I wrote it for her as if she’s singing’. She’s a character. But she was real. And then – “Young Girl Blues” is my wife Linda, who – basically, walked away from modelling. But it was for all girls who were pretty and beautiful, and were expected to do things that they disagreed with, to become famous. And this young girl in “Young Girl Blues” is one who will not play the game, who will not give away her intimacy to get on in a man’s world. So these female… positions, in my songs, are what I brought in. I brought in the ‘feminised male’… in my songs, the songs which I sang. I used words like ‘beautiful’ and ‘lovely’ and ‘kind’ – and they were usually attributed to the feminine part of our race. As if only women had those emotions. And men don’t. Why is that?, I account that to two world wars and the Depression. When men were put in uniform, had their hair cut off, were de-humanised, demoralised, given weapons to kill, until all softness and all humanity was sort-of squeezed out of them. And I brought that back in the sixties into songs. And at first they thought I must be gay. Gypsy Dave will tell you – half my audience in New York and San Francisco at a couple of early concerts were gay, and they were knocking the doors down to meet me. And I’m saying ‘yeah yeah yeah, I’m hetero guys, I’m actually hetero, but I understand exactly where you’re coming from. You have a feminine aspect, and you want to celebrate it’.

In 1965 it was brave – as a man (years before Bowie make sexual androgyny fashionable), to stand out against the mainstream in this way. Yeah, yeah, they would print in the music papers ‘Donovan Thinks The World Is Beautiful’ in two-inch-high letters and – of course, it was really a put-down. They’d say, ‘so you think that kindness and brotherhood, peace, family and humanity are coming back into the world?’ And I said ‘no, they’ve just temporarily gone missing’ and ‘I’m going to sing about them’. So, yeh, I was doing all that – singing from other points of view. I have children’s songs as well.

So getting your first American no.1 single (September 1966, opening up the second, and most massive phase of his career) must have seemed like a vindication of that philosophy. Getting what? – oh, a no.1, yes. “Sunshine Superman” was very important. A no.1 in America was extraordinary, it was more extraordinary than that because the record had sat in the courts for nine months (in a legal dispute), which means that I made the ‘Sunshine Superman’ album in late-1965 and early-’66. Which, by the way, was a year-and-a-half before ‘Sergeant Pepper’ – and ‘Sunshine Superman’ was just sat there. My book tells all about it. My producer Mickie Most said ‘don’t play advance copies of this to Paul (McCartney)’, but of course I played it to Paul, because we make our records for our peers – did you know that? We don’t really make them for the audience. First, we make them for us, then for our peers. Also in the book it tells how I was the first to be targeted by the Drug Squad. I was busted, and following me was the Stones, the Beatles, and lots of other people. So we just said ‘forget all that Court Case stuff’ – and we buggered off, Gypsy and I. We went back on the road. And then – we were in Greece. We were in Greece living on 1s 3d a day in a deserted island with no hotels…

Which island was it? The island of Paros in the Cyclades.

You wrote “Writer In The Sun” in Greece. It has beautifully observed imagery. Lyrics that reveal themselves with the precision of a haiku, about ‘the magazine girl’ who ‘poses’, the next line adding ‘on my glossy paper’, until giving it the final fold ‘aeroplane’. Each phrase building another level towards the full final image. So you wrote that on Paros? “Writer In The Sun”, yes. I was actually already writing the next album – ‘Mellow Yellow’, although I didn’t know I was writing the next album, ‘cos I didn’t know I’d make another album. ‘Days of wine and roses, are distant days for me,/ I dream of the last and the next affair and girls I’ll never see,/ and here I sit, a retired writer in the sun’. And it really felt like that. I was there, I had my books, and I was writing songs. And we were there until we got a telephone call that took three days to come through, because that was the way it was in those days. There was only one telephone on the island. Gypsy and I took the call in a taverna and my manager said ‘come back to Athens immediately, your record is finally released and it’s no.1 all over the world’. So we took out what money we had and we put it on the table and it added up to… like, nothing. We couldn’t even afford to get the tramp steamer back to Athens. Then the taverna-owner saw a portable record-player/tape-recorder that I’d brought in a brief-case – one of the first out of Japan. We had three records, I had (the Beatles) ‘Rubber Soul’, Leonard Cohen, and my white album – not ‘white album’, but my white-label first demo-pressing version of ‘Sunshine Superman’. And he looked at the record-player and he said ‘how much for the record-player?’ So we sold the record-player for the steamer-ticket back to Athens where the First Class tickets were waiting. So – I waved goodbye to that Greek island, but – in my book, I realised I was waving goodbye to a way of life I would never live again. And that was a great sad farewell to a bohemian side of me. Then we were back in business again…

Was it scary achieving that level of success, opening up the expectations it inevitably entailed? Now, a no.1 hit record means you get a heroin-chic girlfriend, you thump a paparazzi outside the nightclub, you detox, then get dropped by your record label when your third single only gets to no.13, only for your career to get resurrected by an ‘I’m A Celebrity Island’ Reality TV slot. Back then it was different. Back then you were the Pied Piper. Voice of a Generation. Shaman. All that weight of belief and expectation. I once asked Jefferson Airplane’s Grace Slick the same question, if she found her success-levels scary, and she said ‘no, it was fun’. Well, it was fun to begin with. And… although I took it as an accolade, and – in a way, the success I deserved, ‘cos I’d worked so hard on my ‘masterpiece’, none of us – the Beatles, the Stones, I – or any of us, expected that kind of mania. I talked to Lennon, and I talked to Joni Mitchell about it – did you intend it, do you actually want to do this? It wasn’t a stroke of luck all the way, was it? You wanted to do it. So we knew we were going to do this. But the shock was, the amount of the success. Until it got – it became dangerous for the fans, and for us. We had to invent security systems for the fans, and us, and really – we had to invent what they call ‘minders’ to look after us, but in looking after us, also looking after the audience. ‘Cos the police used to bring dogs and when the audience got excited they’d set the dogs on them! Things like this. That was scary. That the actual fans were being treated like that. Yet I took it on, as all my contemporaries did. Took on the mission to introduce bohemian ideas to popular culture. Because bohemia provides the possible cures for the illness of society. Karl Jung – the psychologist says ‘the modern societies of the world suffer from a grand complex which has been imposed upon them for thousands of years by church and state’. That situation had to be addressed. We didn’t realise the un-tapped restraint that the world had endured in the fifties, the conventions, the conditioning, all that was breaking, we were breaking it! So – there’s a calling. And we were called. With the result that now, what’s let loose upon the world is freedom. Freedom to express yourself in any form that you want. And that’s what the sixties – in my book, says. It’s a door that was opened. Doors of perception. That was Aldous Huxley’s book – ‘The Doors Of Perception’. And the American band The Doors took their name from that book. So, my book addresses a lot of things that were going on in the sixties.

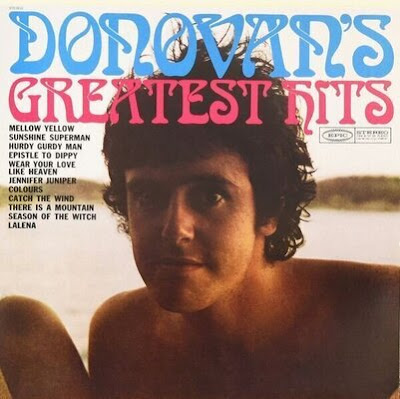

So how does Donovan react to such success-levels? He gets another no.1 with “Mellow Yellow”, then follows it with further top five hits “There Is A Mountain” and “Hurdy-Gurdy Man”. Only, for a long time there was a persistent confusion over UK and USA release schedules, with some tracks (despite Amazon) only available in America. A rationalisation process was long overdue. That’s because the ‘Sunshine Superman’ (October 1966) and ‘Mellow Yellow’ (March 1967) albums were moving so fast that in America they had all the records complete, but in England they put half of ‘Sunshine Superman’ and half of ‘Mellow Yellow’ together to make – that’s the one (pointing to the CD I’m holding up for him to autograph), and they didn’t even release the complete album ‘The Hurdy-Gurdy Man’ (US December 1968) or the complete album ‘Barabajagel’ (US October 1969 – recorded with The Jeff Beck Group) at all, just some of the tracks as singles and B-sides. But now the situation has been corrected by EMI who have re-released the four albums that didn’t get released in the UK in their entirety, they’re all released, with bonus tracks. Which is great because UK fans think they’re listening to something new, something that they’ve never heard before, which is true, they haven’t heard them – unless they collected import American versions.

‘DONOVAN IN CONCERT…’

“My songs are merely dreams, visiting my mind,

we talk a while, by a crooked style,

you’re lucky to catch a few…”

(‘Celeste’)

You once wrote ‘well, I’ve taken every drug there is to take/ and I know that the natural high is the best high in the world’. Adding that, with drugs, ‘they don’t know what they’re doing to the nervous system’ and that ‘laboratory synthetic stimuli only goes to fuck-up your third eye’ (“Ricki-Tiki-Tavi” September 1970). Amusingly, as the track fades out, you hear Donovan asking ‘did the tea get here?’ Yeh, that was at the time when me and the Beatles, and others, were looking at the effect our music was having on millions of people. And the book will explore that further. But basically it was, we were being looked at as promoting drugs. We weren’t promoting drugs. We were doing what every bohemian does – we were exploring, with marijuana, and with LSD which was still legal until 1966. Peyote and mescaline too, the holy plants of the pagan tribes, especially the Native American tribes. So, with these drugs we were, exploring. Then there was synthetics. And I didn’t really get into synthetics, nor heroin, or cocaine. But I tried every one just a little bit. Just to see what it was about. But then we realised. The Beatles and I sat around saying ‘everybody thinks we are promoting it’. ‘What we really want’ says George Harrison, ‘is to discover how to go inside without drugs’. And that’s meditation. And we want to know. So we sought out a Yogi, and we found one. We told the world we’re going to India, we’re going to do it, and we’re stopping taking drugs and alcohol, we don’t care what you lot are doing, ‘cos that’s not what we’re about. And so, we went to India, and we studied. But then, when that word came out into the world – meditation, millions of people wanted to know what it was. So then we were promoting another part of the bohemian manifesto, the spiritual path, how to explore your own consciousness without endangering your health. Meditation is the safe way. And we brought it back. And we promoted meditation. And that was a good thing. The natural high. (If what he says here sounds like excessive name-dropping, it’s all true and well-documented. Paul McCartney appears on his “Mellow Yellow” session, Donovan guests on Beatles recording sessions – singing along with the chorus of “All You Need Is Love” at Abbey Road, and yes – they all went to India together to the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi’s ashram, at Rishikesh by the Ganges.)

After all of that high-profile celebrity, it must have been a strange period of adjustment for you when the hits stopped, abruptly, in the less hospitable 1970’s. But I made nine albums in the 1970’s, and they also explored further developments of bohemia. Although it’s true they weren’t so hot on the charts. You can’t have a renaissance every decade. (Those albums include his ‘experiment in Celtic Rock’ ‘Open Road’ (September 1970), the double-album ‘HMS Donovan’ (July 1971), a re-union with Mickie Most for ‘Cosmic Wheels’ with Chris Spedding and Cozy Powell (Mar 1973), ‘Essence To Essence’ produced by Andrew Loog Oldham (February 1974), ‘7-Tease’ recorded in Nashville (December 1974), ‘Slow-Down World’ (June 1976), ‘Donovan’ – also with Mickie Most (October 1977), and ‘Love Is Only Feeling’ (November 1981) – its title quoting his own “Someone Singing” from his ‘Gift From A Flower To A Garden’ double-album box-set.

Don’t you ever get tired of talking about those dim and distant 1960’s? Well – this is not talking about the sixties. It’s talking about the bohemian manifesto that was set loose upon the world. I’m not getting tired of it because I’m still actually promoting it. My Fortieth Anniversary is not promoting the success of Donovan, but promoting the work of Donovan, which reflected every aspect of bohemia. I wrote about its every aspect. I’ve got at least one song that relates to each of the new movements that entered popular culture. Of course – those movements were not really new, they were very very old. Bohemian culture has contained these movements for hundreds of years, all the way back – recently, to the 1840’s in Paris where the first Bohemian cafes began in the modern world. But you can go back further to ancient Greece or Renaissance Italy and you’ll find taverns where artists gather, thinkers gather, painters gather, radicals gather (a litany he expresses like a rhythmic chant, an incantation, a poem). Something happened in Italy in the Renaissance which was extraordinary. It changed the world, and re-established what I call bohemian ideas. That means, true ideas. And so what I’m talking about is not historical, it’s a continuity. I’m not going back to the sixties, it just so happens that the work I’m going to present – the body of that work, comes from the sixties.

And – er, I go on stage at eight… so, I can only afford another ten minutes. And you’re not even looking at your questions. I’ll get to them later. No (playfully), you’d better get to some key ones in case you say to yourself later ‘oh, I didn’t ask him that one…’ OK, I’ll ask you about “Celia Of The Seals” (March 1971), a song that uses Celtic mythology to comment on the brutality of the so-called seal-‘culls’. It does, yes. And it’s about a model called Celia Hammond who walked away – purposely, from modelling. She was a top model – Celia Hammond (and Linda’s close friend), and she refused to wear fur because she realised that they were killing animals. She went up to the ice-floes with Brigitte Bardot and protested against the seal… they called it ‘seal culling’, which is really the seal-killing. And I asked my label in America if they would carry a photograph of a seal-hunter walking across the ice carrying his knife with blood on it, and a poor little seal with its skin cut off, and its mother crying beside it – and they said ‘yes’. So I recorded the song called “Celia Of The Seals”. And it was about the seal hunts. But it mixed mythology with it. Because in far northern Scottish mythology the seal-people and the humans, they would mate, and seal-children would be born. Of course – it’s a myth, but it’s a beautiful myth. ‘Cos the seals, just like the dolphins, are intelligent. And they say that they lived on the land once, and that they ran around, but that they eventually returned to the sea, just like the dolphins…

And so… you’re last question? Well – much later, during the 1980’s, you toured with Happy Mondays – who also wrote and recorded a track called “Donovan” on their ‘Thrills Pills & Bellyaches’ album (1991), which quotes “Sunshine Superman” lyrics. Did you see any similarities with what they were doing, and the 1960’s drug scene? Mmmm, Happy Mondays. The Mondays were the Rolling Stones of the eighties, they were incredible. And those young bands respect me, ‘cos I take chances, because I break the rules. I broke the rules in songwriting and recording. And that’s an inspiration to a young band. Because they feel they have to follow a certain line… and I say ‘no’! Don’t follow any lines. Break the rules. And the Mondays loved that in me. So, well, they came looking for me. And they found me. I was doing solo gigs up north somewhere, I can’t remember where it was, not a big town. I was with Julian – my stepson, Linda’s boy (Julian Brian) with Brian Jones. He was acting as my Roadie. And there was a knock on the door. Julian answered, he went and I heard him say ‘I’ll ask’, then he came back and said ‘there’s five guys here from Manchester, they’re called the Happy Mondays and they want to take you now, capture you, put you in their van and take you to the ‘Hacienda’’… So, we met, and I hung out with the Mondays and went on six of their performances with them. Then Shaun (Ryder) fell in love with my daughter, and his brother Paul fell in love with my other daughter. And there’s a beautiful grandchild from Shaun with my daughter Oriole Nebula, called Coca (Sebastian). And so… that was Madchester. It was the eighties. And I was sitting in a pub with Shaun in Manchester once, and a young man came up and he said ‘Shaun, I’m going to do exactly what you do. I’m going to do what you’re doing’. And Shaun looked at him, and didn’t say a word. And the guy walked off. He was tall and good-looking, had long hair, he was in jeans and T-shirt. I said ‘who’s that?’ He said ‘oh, it’s just a singer, a fucking singer in a band’. I said ‘I think he means it Shaun. I recognise that look. I had that same look in my eyes when I was eighteen. I knew what I was going to do’. He said ‘naw, they’re rubbish, you know?’ Next Friday I turned on the television, and it was Oasis. It was Liam who had come up to us. It was Liam who had said ‘Shaun, I’m going to do exactly what you did’. Of course, there was all this inter-band rivalry between the Manchester bands, and now – over the ten years since, Manchester has continued to produce extraordinary bands. In a way, just like Liverpool had done. Black Grape was also incredible. You got Stone Roses, and the Charlatans – who recorded my “Season Of The Witch”, and more recently another band that really took me by storm – Starsailor. I think they’re incredible. I was on stage with Starsailor at Glastonbury a couple of years ago. And so, I have this relationship with bands. And my songs, songs of mine become standard warm-ups for bands. “Season Of The Witch” is a standard warm-up song for thousands of bands around the world. That’s a kind of fame and appreciation that is real. It doesn’t depend on record sales. It’s that your songs become a part of their life. I think that’s great.

OK Andy, there it is. And I hope you’re coming to the show tonight…?

I assure him I will, as I pass across a copy of my own poem-collection ‘Euroshima Mon Amour’, saying ‘here are my poems for you’. ‘Ah, you have a new publication yourself? ‘Euroshima…’ ha-ha-ha, I love that! thank you for the book. Thank you man. See you later…’ It’s only then, as he’s walking away, that I remember the other questions I should have asked him. The ‘oh, I didn’t ask him that one…’ syndrome.

The question about do you – did you, believe what the press says about you? Have you ever been sampled (“Mellow Yellow” would make a great sample)? About ‘The Observer’ review he wrote about Bob Dylan’s ‘Chronicles’. And about how, on the live ‘Donovan In Concert’ album (September 1968) he improvises ‘I’m just mad about… fourteen-year-old girls.’ Of course, it was a different time, with different rules. Children, and a childlike state was then seen as a kind of Pre-Raphaelite ideal-state of precociously idealised innocence, enlightened by Freud’s discovery of ‘infant sexuality’. Today such a statement takes on more sinister abusive elements. But I guess, if his belief in the natural innocence of children, and childlike innocence, is now tarnished, then that’s our loss, not his.

“I dig Donovan in a dream-like, tripped-out way

his crystal images tell you ‘bout a brighter day’

(“I Dig Rock ‘n’ Roll Music” by Peter Paul & Mary)

Featured on:

‘SOUNDCHECKS’ website

(February 2006)

See also:

No comments:

Post a Comment